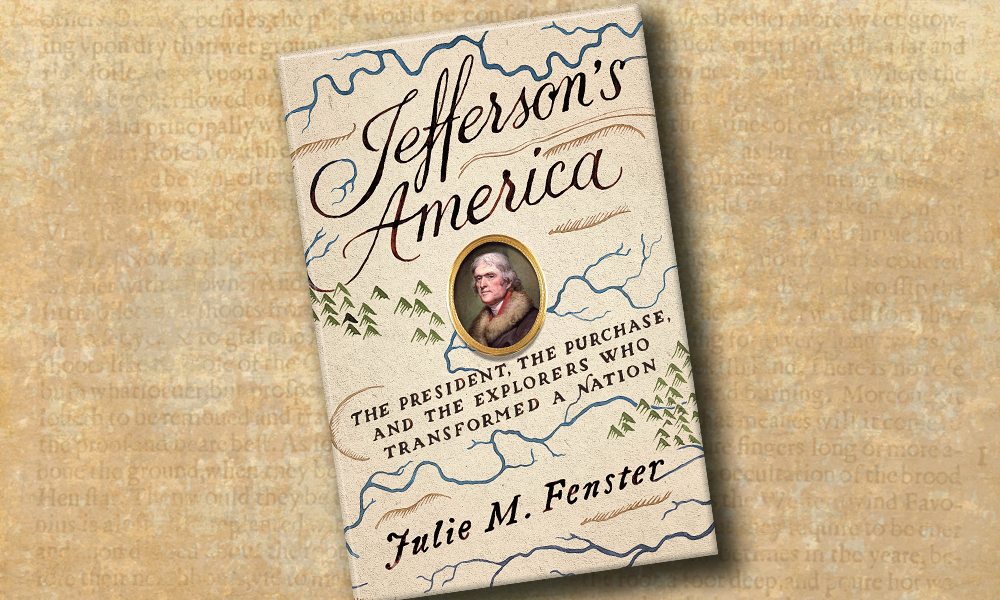

Someone once said, “Shakespeare has tragedies, the rest of us just have messes.” Fortunately for President Thomas Jefferson, his vision of a continental nation from the Atlantic to the Pacific did not end in multiple military tragedies against the British, French and Spanish Empires for control of North America between 1801 and 1809. Rather, he satisfied his Western ambitions with a series of challenging, diplomatic engagements that avoided war with the three Empires, a foreign invasion or loss of territorial gains in the Trans-Appalachian West, the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleonic France, the peaceful transference of the Mississippi River Valley from Spain to the United States, and five successful surveys of the continent’s interior. The complexity of the Virginia-born president’s diplomatic maneuvers is expertly detailed in Julie M. Fenster’s Jefferson’s America: The President, the Purchase, and the Explorers who Transformed a Nation (Crown, $30).

Fenster succinctly states in her opening chapter: “The fact that the Jefferson administration is best known for the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and not for the disastrous War of Louisiana—a war that was soberly expected, but never occurred—is the result of a diplomatic attitude that reflected Jefferson personally.”

As an American historian interested in the origins of our nation as it relates to the growth of the Western United States, frontier and Manifest Destiny history, I highly recommend Fenster’s masterful, complex tale of jealousy, rivalry, ambition and greed. She spins a masterful, adventure-filled tale of intrigue, diplomatic maneuverings, and nimble political deal-making for Western lands. Her conclusions on Jefferson’s presidential aspirations for Western expansion will permanently cement any doubts that the Virginian is the father of the American West.

Equal to my praise for Fenster’s interpretation of Jefferson’s ambitions in the West is my conclusion that the underlying strength of Jefferson’s America is her highly detailed chronicling of the five major Western surveys—and the men who led them—chartered under the third president’s leadership. In addition to recounting Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s Corps of Discovery’s legendary round-trip journey to the Pacific, Fenster details Zebulon Pike’s back-to-back Upper Mississippi and Rocky Mountain expeditions in 1805-1806 and 1806-1807, William Dunbar and Dr. George Hunter’s expedition up the Ouachita River in 1804-1805, and the Red River survey of 1806 by Peter Custis, Thomas Freeman and Richard Sparks.

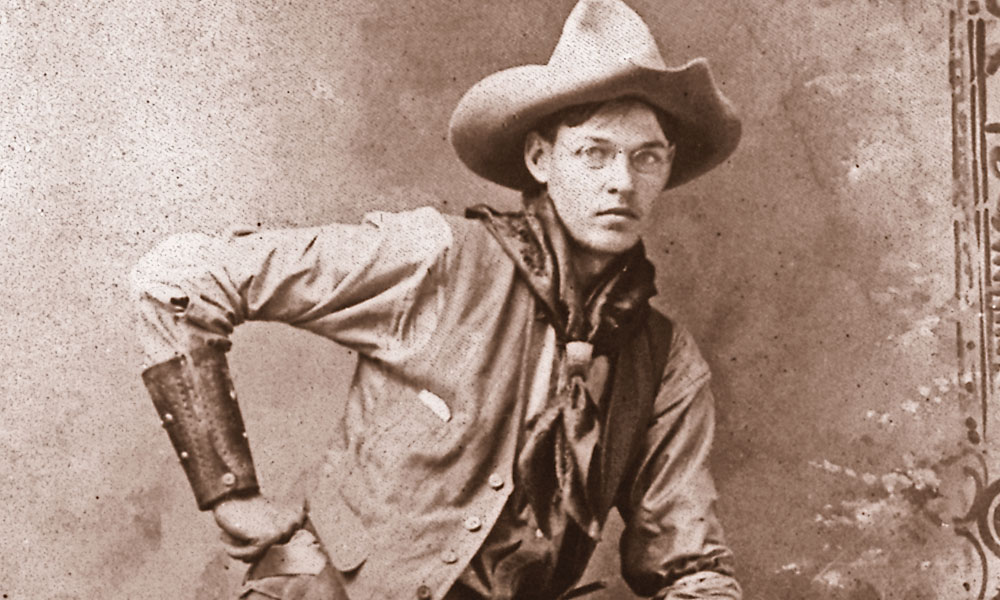

She also provides insightful vignettes on lesser-known Western bravados, including Welshman John Evans, who was determined to discover the lost tribe of redheaded Welsh Indians, even if it meant imprisonment and serving at the behest of the Spanish Empire; and the short but courageous life of Irish mustang hunter, Philip Nolan, who was the earliest of America’s storied Westerners, personifying the tradition of folk-hero cowboys who thrived on the open range, riding herd by day with a posse and making the most of an open campfire every night.

Similar to fellow Crown author Paul Andrew Hutton’s The Apache Wars, Fenster’s Jefferson’s America does not stray into modern politics or attempt to draw in empirical politics or political correctness of the 21st century into its research or conclusions. The independent historian from upstate New York provides a balanced, very detailed story of the Republic’s growth and continental ambitions in the first decade of the 19th century that must be understood to gain a greater foundation of American continental ambitions—and relations with European rivals and Native tribes across North America.

Fenster allows readers to draw their own conclusions on Jefferson’s successes and failures as president. My conclusion: America’s author of the Declaration of Independence would die 17 years later with a view of the Blue Ridge Mountains and the blue, boundless Western horizon from his beloved Monticello on July 4, 1826 with full knowledge that his Westward vision of America—and the courageous surveyors who walked where he could not—had successfully platted a national direction Westward—no matter the unknown challenges of the trail ahead.

—Stuart Rosebrook