– Photo Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection; All Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

We have brooded and argued and mulled over this fictional tale of Mickey Free for years now—sort of a personal Heart of Darkness. Our goal was a graphic novel that would be the basis for a film. Our journey became a metaphor for what we were attempting—a crazy cross between Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, B. Traven’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, that ultimate dark road trip.

Our cast of characters are the poster children for American Exceptionalism (and we don’t know if that’s good or bad): the mixed-race, one-eyed outcast Mickey Free (our Huck Finn), the happy-go-lucky, cold-blooded killer Tom Horn (our Tom Sawyer) and the ex-slave narrator Jim Young (our escaped slave Jim). Throw in the deeply wronged and consistently romantic Apache Kid, the revolutionary bandit Pancho Villa and the displaced Russian aristocrat and Sonoran warlord Emilio Kosterlitzky, and you have a supporting cast to literally die for.

These fascinating characters move ever deeper into what author Richard Grant labeled as the “lawless heart of the Sierra Madre” in a darkly violent dance of death. Here are the real characters who inspired our graphic novel and the truths behind the fiction. Although Mickey Free’s hunt for the Apache Kid exists only in our minds, history reveals how such a magnificent hunt almost materialized.

EVOLUTION OF A MAN HUNTER

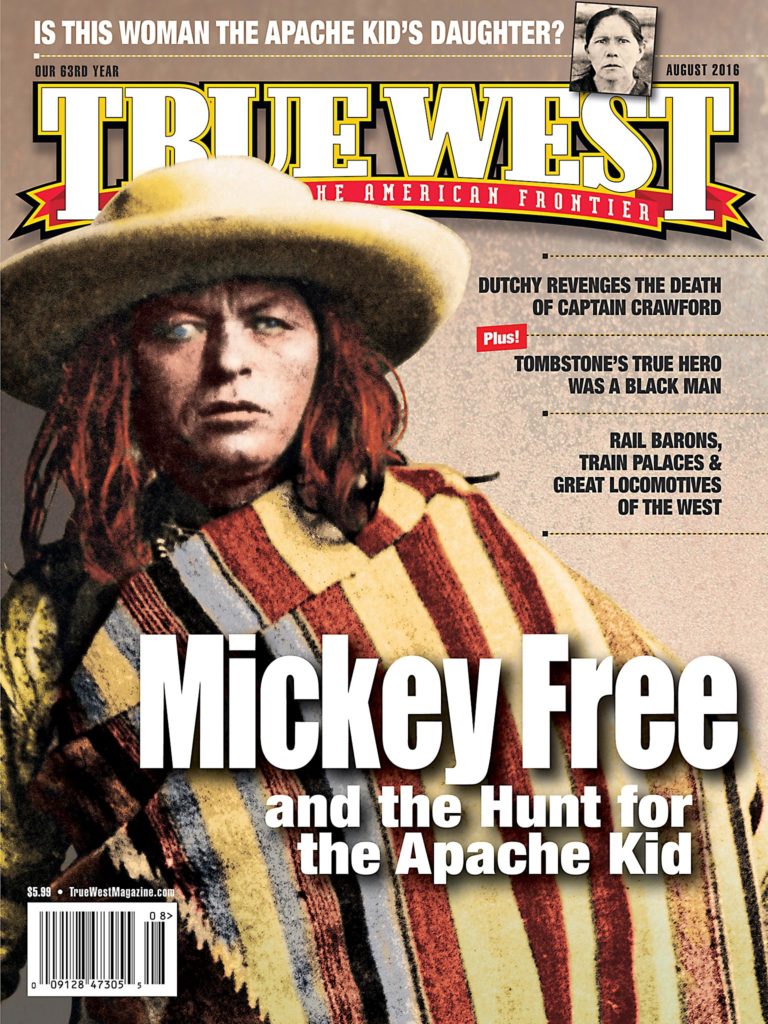

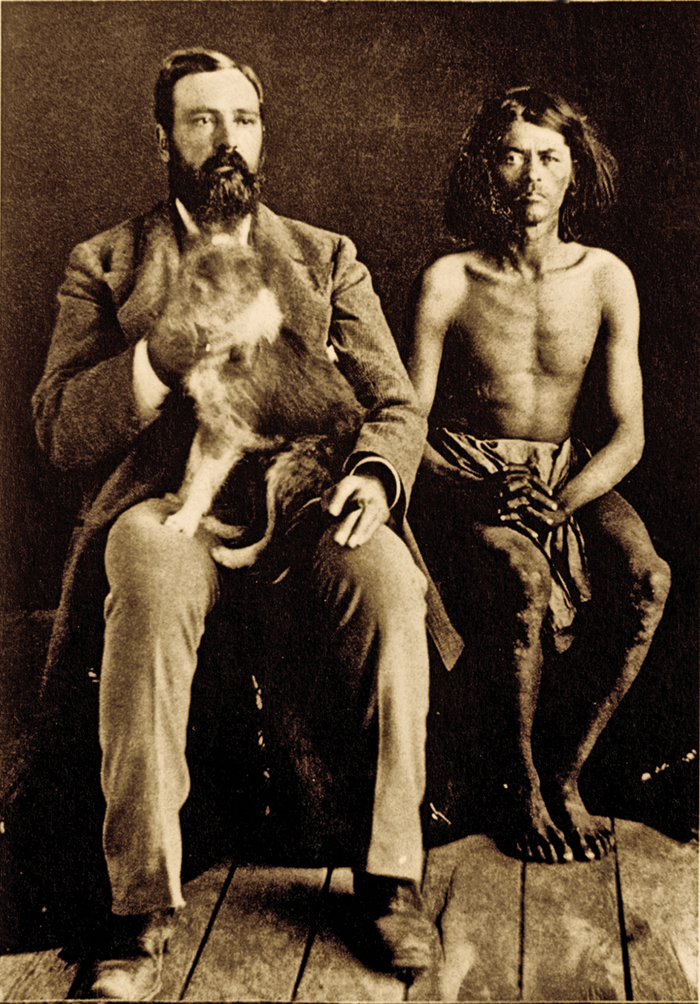

Mickey Free evolved slowly from the young Apache captive into the famous—or should we say notorious—U.S. Army scout. In the circa 1877 photograph at Arizona’s Camp Verde, we see a scrawny, nondescript boy. He has obviously befriended the post trader, so that he—along with the pup “Boss”—is included in the photograph. Although he looks similar to other Apache scouts, the boy was scrawny and slight for his age, which made him appear younger than his age. His youthful look probably saved his life when Beto raided the Ward ranch in 1861.

Within a few years, Mickey Free had transformed himself into a legendary scout and man hunter who was the talk of Apache Country. Donald McIntosh, the mixed-blood son of Crook’s scout from the Pacific Northwest, Archie McIntosh (brother of Lt. Donald McIntosh, who died with George Custer at Little Big Horn), recalled Free from the 1880s: “I was only fifteen years old then and I had never seen anything quite like Mickey Free. He had big cavalry boots on, the kind that came up high above the knee…and a big pistol belt around his waist and in it he carried two big dragoon pistols. He presented a fine figure in the prime of his life.”

Full disclosure: In our graphic novel, Mickey Free speaks Apache, Spanish and English, but Free did not speak English. He did scout for the U.S. Army, and, in fact, did go in search of the Apache Kid, with some claiming he actually bagged the Kid.

ROUGH SHOD PAPA

Chief of Scouts Al Sieber was “somewhat” of a father figure to Tom Horn, Mickey Free and the Apache Kid. He represented the law at San Carlos, and they all rode together dispensing rough justice on the reservation. When the Kid broke out, after a shoot-out that crippled Sieber for life, the old gang was broken up. Sieber never forgave the Kid. The old adage, “When one son, leaves, another returns,” applies to Sieber’s relationship with Mickey and Horn, who worshipped him.

Full disclosure: In our graphic novel, Al Sieber is barely mentioned, but we felt his presence both shaped and hovered over Mickey Free and Tom Horn.

SLAUGHTER’S MEXICAN RANCH

“Texas” John Slaughter first settled on the San Pedro River, but bought the abandoned San Bernardino Ranch a few years later. What most history buffs don’t realize is that Slaughter’s new ranch went deep into Mexico. This area may be where Young, who worked for Slaughter, tracked the Apache Kid to one of his favorite watering holes. Young admitted as much to a surveyor in Tombstone, Arizona (see Unsung).

Because of several springs and good water, Slaughter’s ranch became an active place not only for travelers, but also for the U.S. Army. Troops used the ranch as a staging area to launch forays into Mexico to chase after various Apache renegades, including the Apache Kid. In March 1886, Gen. George Crook and his scouts met at Slaughter’s ranch before crossing the border to meet Geronimo at Canyon de los Embudos, which is just east of the Slaughter property in Mexico (see above map).

About 75 percent of Slaughter’s Ranch was in Mexico, which stretched some 14.6 miles south of the border into Sonora. Over the years, Slaughter purchased, leased and homesteaded vast tracks of additional land. At one point, he controlled about 100,000 acres. After his death in 1922, Slaughter’s widow, Viola, leased out the ranch for several years. But when family members decided to sell it, the Mexican government required that the portion south of the international line be sold to a Mexican buyer.

—Reporting by Tom Jonas

Full disclosure: In our graphic novel, Jim Young, Mickey Free and Tom Horn go on the hunt for the Apache Kid. Although this never happened, Young and Horn were almost sent on the assignment in 1896. Horn did, however, hunt the Kid with the Seventh Cavalry that summer. They went into Mexico from Slaughter’s ranch and ran into Col. Emilio Kosterlitzsky and his troops. The two joined forces, but Horn returned to San Bernardino on July 22 after a “difficult and unsuccessful patrol.”

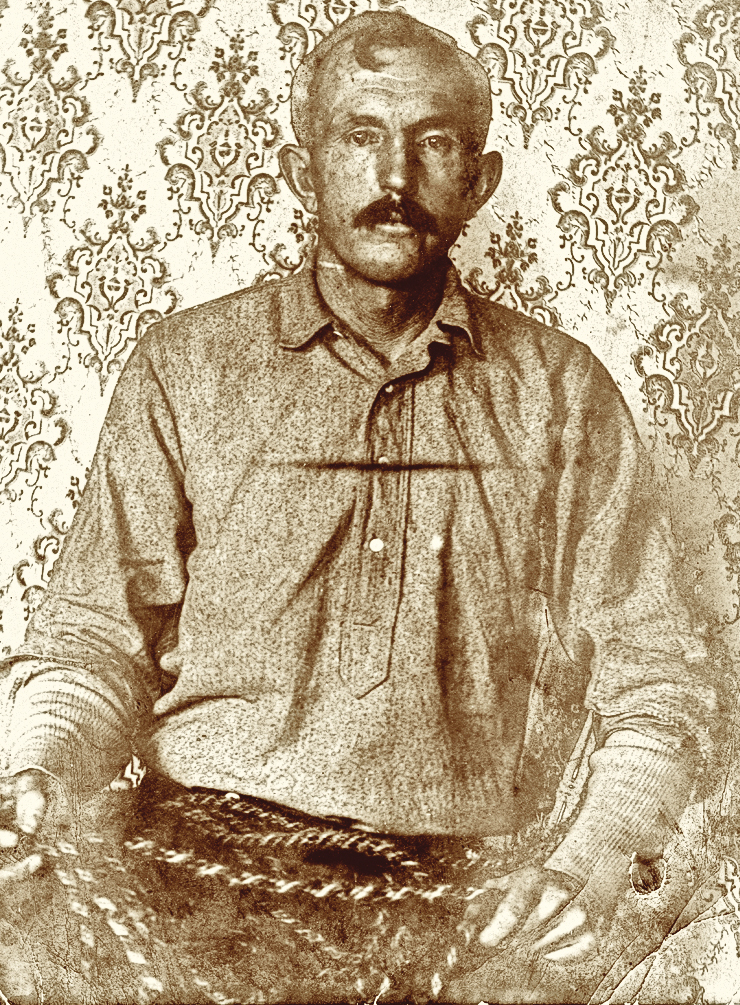

TALKING BOY

The Apaches called Tom Horn “talking boy.” He thought he earned the nickname because he spoke their language, but they called him that because they so admired his gift of gab. No one could spin a tale quite like Horn. He eventually talked himself right into a hangman’s noose.

The wild exaggerations and half-truths in Horn’s 1904 memoir have led many to dismiss him as a fraud. For instance, Horn claimed that the Kid had died of consumption, but offered no proof to substantiate that claim. Regardless, we should not forget Horn was the real deal—not only as a hired killer, but also as a scout in the Apache Wars. He ran away from his Missouri farm as a teenager to find adventure on the Santa Fe Trail. In Prescott, Arizona, the tall, lanky and good-natured boy fell in with master packer Long Jim Cook, who hired him as a “scrub” or apprentice mule packer for U.S. Army supply trains. At Fort Apache, soon after the 1881 Cibecue debacle, Horn came to Al Sieber’s attention. Sieber took a liking to the boy and recruited him as a scout, alongside Mickey Free and the Apache Kid.

Horn proved instrumental in the Geronimo campaigns led by George Crook, Emmet Crawford and Henry Ware Lawton. Years later, men would puzzle over how the famed scout could have become a brutal hired killer, but Jim King, who knew him well in Arizona, explained that Horn’s days with Sieber “had the idea baked into his very soul that there was nothing wrong in killing renegade thieves.” Horn’s tutors, King declared, “were savage Apache warriors.”

Full disclosure: In our graphic novel, Jim Young partners with Tom Horn. In real life, however, Horn reported to officials that Young gave “me a great game of talk” and admitted to seeing the Apache Kid only once. Horn concluded Young was a “liar of the first water.”

THE APACHE IN THE THREE-PIECE SUIT

The Apache Kid was far more photographed than his New Mexico counterpart in Kid-dom, Billy the Kid.

A remarkable March 1886 photograph allegedly shows the Apache Kid at the Geronimo surrender—wearing a natty three-piece suit. C.S. Fly took the photo, and two others, of this group of three Apache scouts. He, or his wife, later identified the fancy-dressed scout as the Apache Kid. (The inset portrait is an attempt to show how he would have looked in authentic Apache garb.) William Sparks, in his valuable little 1926 book, The Apache Kid a Bear Fight and Other True Stories of the Old West, also identified the man in the suit as the Apache Kid. Sparks knew the warrior, so this added credibility to Fly’s identification. But historian Granville Stuart claimed, “This is not the Kid.”

That the Apache Kid would so thoroughly adopt the clothing of the White Eyes fits in well with what we know about him before the 1887 shoot-out with Al Sieber. He was an Apache boy, raised among the whites, who had committed himself to their way of life.

Mickey Free, on the other hand, was a coyote—a trickster figure—who never committed to any side. His clothing remained an outlandish combination of the Apache, Mexican and Anglo worlds. In the end, the Apache Kid reverted back to his Apache origins, while Free committed ever more firmly to the White Man’s laws. Thus, Free went out to hunt down his old friend Apache Kid.

Full disclosure: In our graphic novel, the Apache Kid wears the head band shown on him in these photos. Given the controversy over these photos, we cannot definitively state he wore this headband.

– True West Archives –

THE NORSKY CONNECTION

In August 1890, an expedition took off from Bisbee, Arizona, bound for the Sierra Madre. Backed by the American Museum of Natural History, Norwegian ethnologist Carl Sofus Lumholtz led the massive caravan of eight scientists (including Swedish botonist C.V. Hartman), 21 mule whackers, guides and more than 100 horses, mules and donkeys.

Lumholtz traveled in style, bringing large quantities of honey and his library for reference, all carried by mules and donkeys. He spent more than seven years in the Sierra Madre. The resulting two-volume set, Unknown Mexico, published in 1902, inspired another Norwegian scientist, Helge Ingstad, to follow in Lumholtz’s footsteps. He discovered what many believe is the Apache Kid’s daughter (see Lynda A. Sánchez’s article).

Full Disclosure: Helge Ingstad went to find Lupe in 1937, and Jim Young died in 1935, so the two never knew each other. A Tucson Citizen reporter did not interview Young, and their conversation was created as a narrative device.

– True West Archives –

THE MAD RUSSIAN

Some called Col. Emilio Kosterlitzky the “Mad Russian,” and while he was perfectly sane, his life, nevertheless, read like something written by an inmate of an insane asylum.

Born in Moscow in 1853 to a Russian father and German mother, he was raised in Germany before entering military school in Russia. He became a naval officer, but deserted his post in 1872 while in port in Venezuela. Within a year, he had enlisted in the Mexican army, where he became a favorite of dictator Porfirio Diaz. In time, he became the warlord of Sonora, respected by all on both sides of the border for his courage, integrity and Old World sense of gallantry. A master of language, he spoke Russian, Spanish, German, French and English, and was renowned for both his iron will and disarming charm.

Kosterlitzky made his rurales the terror of bandits, both Gringo and Mexican, as well as the Apaches and Yaquis in his territory. In his own way, he was as much a shape-shifter as Mickey Free. Here, he poses in formal uniform, with the spiked Prussian helmet favored by many armies in the late-19th century, as well as in full Mexican sombrero, alongside former Rough Rider and Arizona Ranger Tom Rynning.

In May 1890, Col. Emilio Kosterlitzky led a small detachment of his rurales out after a band of smugglers. They found the men, but they were all dead. A fresh Apache trail led south from the scene. After a day of hard riding, the rurales came upon a rocky outcropping in an immense plain. The Apaches lay in ambush, but Kosterlitzky sent his large hunting dog in first, to sniff out danger. The rurales charged in response to the barking dog and, in a sharp fight, drove the Apaches off, with the loss of two of their men. Three Apaches lay amongst the rocks. As the colonel inspected one of the bodies, he discovered an ornate gold watch with images of cattle and sheep, and the name Glenn Reynolds engraved on it. He also found a pistol with the name Reynolds etched in the grip. The dead Apache was a gray-haired older man, so Kosterlitzky knew he had not found the Apache Kid. The colonel forwarded the watch and pistol to Mexico City officials. The artifacts were sent to Secretary of State James G. Blaine, then to Arizona Governor Lewis Wolfley and finally back to the Reynolds family.

The fall of Diaz led Kosterlitzky to flee to the United States in 1913, where he quickly found employment as a detective with the U.S. Justice Department. He even worked with the founder of today’s FBI, J. Edgar Hoover. He died in Los Angeles in 1928.

Full disclosure: In our graphic novel, the Mad Russian never encountered the trio in their fictional hunt for the Apache Kid, but he and his rurales did patrol the wild country along the U.S.-Mexico border where Apache renegades hid out.

APACHE WIVES?

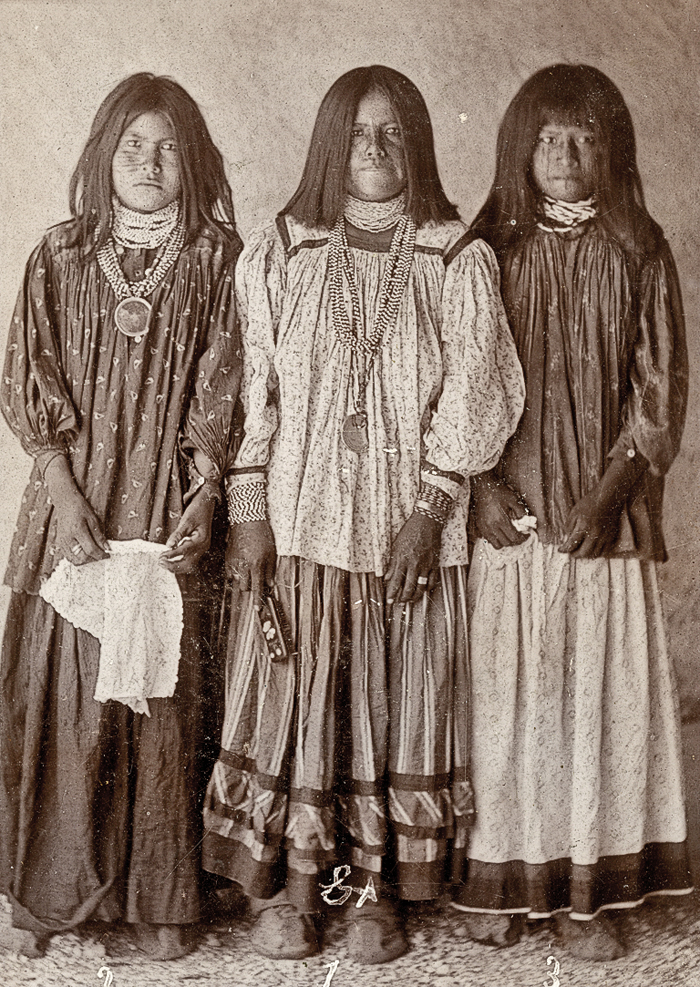

Here is a rare photograph of three Apache girls who claimed to have been kidnapped by the Apache Kid. At the bottom of the photograph, someone has written notes describing specifics of the kidnappings. The first note states: “I-vo-ash-ay, a San Carlos woman abducted from Reservation by Apache Kid in September, 1890. Escaped November 10, 1892 Was employed by troops as guide in pursuit of ‘Kid.’”

She turned an unfortunate experience, her abduction, into an opportunity to track her kidnapper. That she knew the Apache Kid’s hideouts must have helped out U.S. troops.

The second girl is identified by this note: “Na-thethlay, a San Carlos girl stolen by ‘Kid’ after he had killed her mother, May 17, 1892. The girl was turned loose 5 days later.”

How heartbreaking. Imagine cooking and cleaning for the brute who killed your mother? No wonder he let her go five days later; she was probably inconsolable. At the same time, historians do not recall any incidents in which the Kid killed a mother, but Massai, another renegade, did kill mothers. Perhaps the two Apache outlaws are getting mixed up here.

The third girl is described as: “Nah-tah-go-yah, San Carlos girl stolen by ‘Kid’ from Reservation October 25, 1892, retaken by troops from San Carlos December 27, 1892, when ‘Kid’ attempted to recapture Jo-ash-ay, No. 2, above.” (This is confusing because No. 2 is identified as Na-thethlay.)

Altogether, these notations indicate the Kid was active around San Carlos, before he fled for good to Mexico’s Sierra Madre. The existence of these other “wives” brings up the interesting dilemma of how to portray his last “wife,” who gave birth to Lupe (see p. 38), the girl may have been the Apache Kid’s daughter. Did they fall in love? Hard to say, but in our graphic novel, you can bet your boots they did!

Full disclosure: In our graphic novel, we portray the Apache Kid as being in a committed relationship with Lupe’s mother, but given his history with Apache women he captured as wives, that is probably wishful thinking.