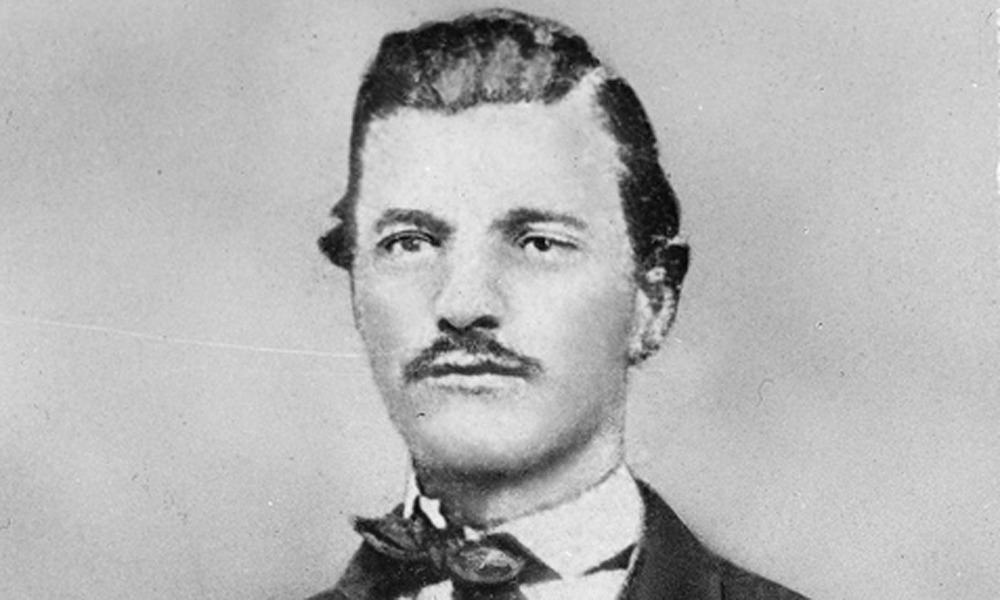

In September 1897, Jefferson Randolph Smith arrived in Skagway, Alaska, to make his fortune. Most people headed north to strike it rich in the gold fields. Smith had other ideas.

In September 1897, Jefferson Randolph Smith arrived in Skagway, Alaska, to make his fortune. Most people headed north to strike it rich in the gold fields. Smith had other ideas.

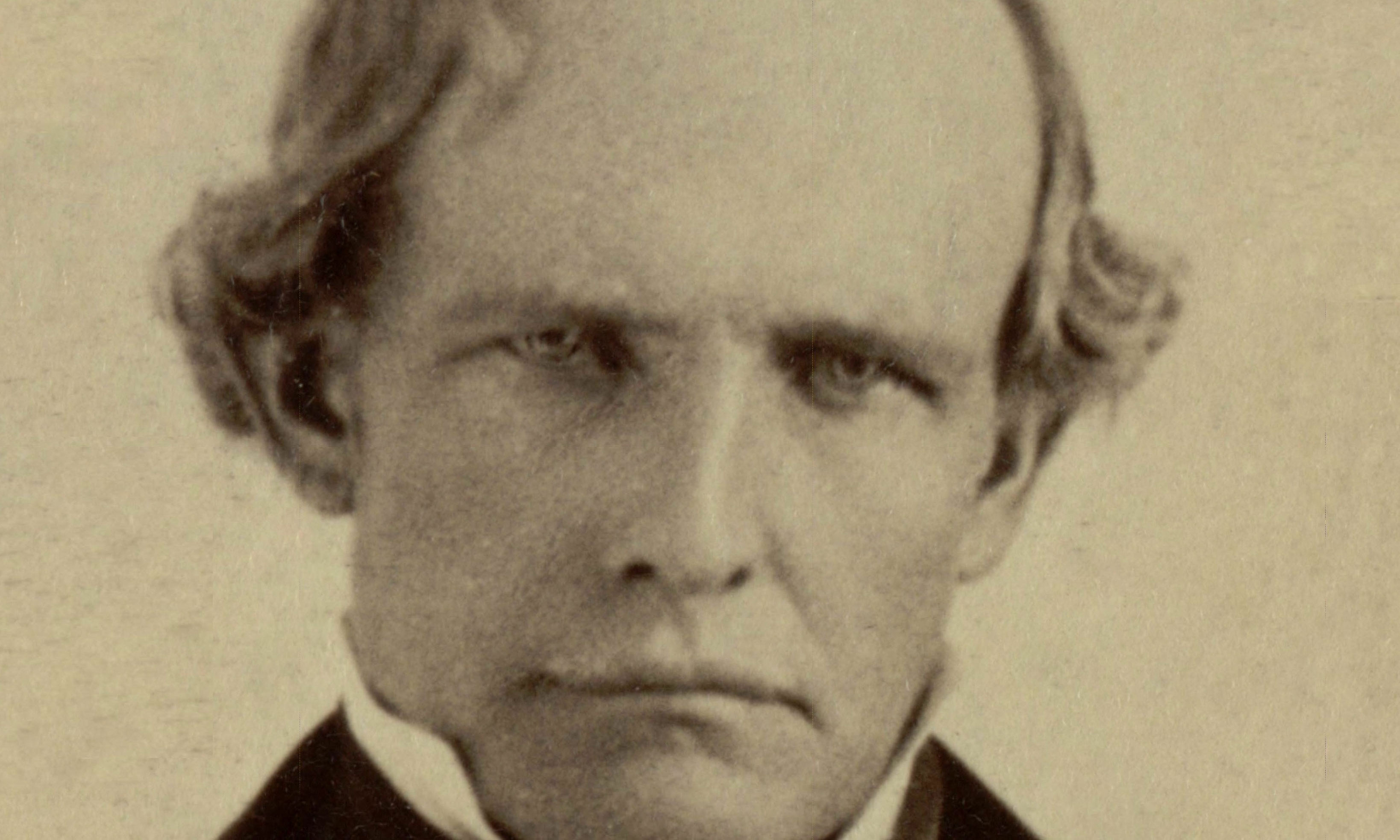

Smith was already better known in various American locales as Soapy Smith, the king of the con men. He knew how to separate a fool from his money, and Alaska was prime territory for a con man with big ideas. Smith reportedly told a friend, “I’m going to be the boss of Skagway. I know exactly how to do it….”

Smith gained a foothold in Alaska as a major investor in at least two saloons, a merchants’ exchange, a real estate company and a telegraph office (three years before the telegraph arrived there!). On top of that were the various con games he and his associates ran on the streets.

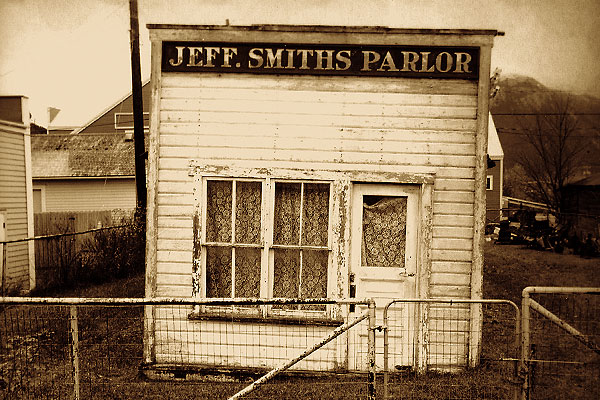

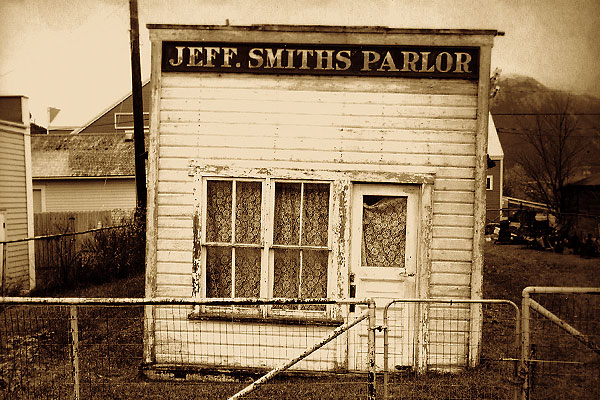

But his pride and joy was Jeff Smith’s Parlor, located in a tiny (18 feet by 40 feet) former bank building. In March 1898, he turned it into a saloon, a gathering place and an unofficial city hall of Skagway. It was the headquarters of Smith’s private army and his “law and order” society (one had to maintain appearances). Locals called it “Jeff’s Place” or “Soapy’s Place.”

The fact that Smith put his own name on it shows just how much he thought of his saloon. But he wouldn’t run it for long.

On July 8 of that year, Smith died in a gunfight on a Skagway wharf. You might think his death would spell the end of “Soapy’s Place,” but an investigation into the history of the parlor proves otherwise.

After the con man’s death, one of his pals took over the business. As the Gold Rush faded into memory, the local fire department used the building as a garage.

In 1935, old-timer Martin Itjen bought the building, as well as several others along the street. Itjen had been collecting Skagway items since his arrival in 1898, and he had become the town’s unofficial tourism director. He restored the parlor as a museum that featured local history, including stories about Smith.

Itjen died in 1942, and his friend George Rapuzzi took over the parlor and most of the collection. At various times, he closed and then reopened the museum. He also moved the building a few blocks away from the original location.

Rapuzzi died in 1986 and left behind an amazing legacy—more than 450,000 artifacts, including several buildings, documents, signs, paintings, clothing and even a 1906 street car that Itjen had used to ferry tourists around Skagway.

By 2007, the Rasmussen Foundation—a family-owned foundation that promotes Alaska’s history—bought the Itjen-Rapuzzi Collection and then donated it to Skagway and the National Park Service.

Two years later, the park service began restoring Jeff Smith’s Parlor. Workers lifted the building onto a new concrete foundation and updated the roof and floor, restored and replaced wall paneling and conserved historic artifacts (at a cost of more than $263,000 so far). More is to come, because the park service plans to reopen the Parlor Museum in 2016.

Today’s Skagway thrives mostly because cruise ships stop at the Gold Rush hub. Smith would probably be twirling his moustache at the number of potential marks who come to his town these days (and visit his grave at the cemetery). In a few years, they’ll be able to step into his parlor and see a bit of history brought back to life.

And that’s no con.