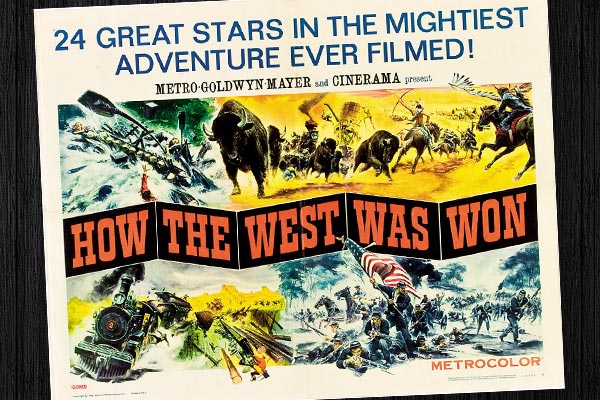

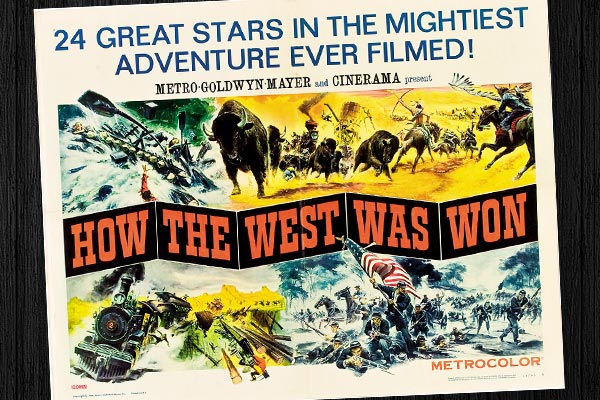

“We sincerely believe that all who see How the West Was Won, will agree that, the motion picture medium has attained its highest level of artistic achievement,” the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Cinerama bigwigs proclaim in the press book.

“We sincerely believe that all who see How the West Was Won, will agree that, the motion picture medium has attained its highest level of artistic achievement,” the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Cinerama bigwigs proclaim in the press book.

What would you expect them to say in 1963? That they had lined up an all-star cast and an estimated $15 million budget to produce a turgid, sappy melodrama that belonged in the roaring ’20s (The Covered Wagon, Tumbleweeds, The Iron Horse), not the about-to-become radical ’60s?

Premiering overseas in late 1962 before opening in America in February 1963, How the West Was Won was an old-fashioned Western in an era that was introducing fresh takes like Lonely Are the Brave, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Ride the High Country and Hud. Fifty years ago, How the West Was Won was already an anachronism.

That was the scope of this opus I planned to write. Then I re-watched the movie. To my surprise, I couldn’t stop watching. Not because the movie is a train wreck, but because … er … it’s … well … kind of awesome.

To make sure I wasn’t crazy, I checked with screenwriter and Western film historian C. Courtney Joyner for his reaction and the buzz about this movie 50 years after its release.

“Obviously, the Cinerama revivals have been very successful—partly because this is the kind of film, and made in a way, that’s truly no longer part of the Hollywood landscape,” Joyner says. “And yet, audiences respond, partly because it’s so different than what folks see at the movies these days.”

How the West Was Won is based on a series of Life Magazine articles from 1959—not a novel by Louis L’Amour, who merely wrote a novelization of James R. Webb’s screenplay. A generational story, it chronicles the Westward migration from about 1839 to 1889 in five segments.

Three directors, well past their prime, but known for Westerns, were hired. Henry Hathaway directed the first two and last chapters: “The Rivers” (Trapper James Stewart falls for Carroll Baker and kills Walter Brennan’s pirates); “The Plains” (Debbie Reynolds goes west with wagon boss Robert Preston and gambler Gregory Peck); and “The Outlaws” (George Peppard stops outlaw Eli Wallach from robbing a train). In the middle chapters, John Ford directed “The Civil War,” in which a young Peppard overhears William Sherman (John Wayne) giving Ulysses S. Grant (Harry Morgan) a pep talk after the first day at Shiloh; and George Marshall directed “The Railroad,” in which Peppard’s disillusioned Army officer protects the railroad and its tyrannical boss Richard Widmark from angry Indians.

Throw in Lee J. Cobb, Henry Fonda, Carolyn Jones, Karl Malden and 2,000 buffalo. Let Spencer Tracy narrate. Film it in Illinois, Kentucky, Colorado, Utah, California, South Dakota and Arizona in Cinerama, a wide-screen process that required three linked cameras and three synchronized projectors.

Epic? You bet. Great history? Not hardly. Flawed? Absolutely.

Courtney thinks Reynolds sings too many songs. I’m president of the I Hate Andy Devine Club.

Courtney’s favorite moment is when Stewart smashes Brennan in the face with a chair. Mine is Ma Baker’s farewell to son Peppard.

We both love Preston’s performance.

Successful? Well, the movie grossed $50 million worldwide, won three Oscars and was nominated for five more. But how would it play today?

“Would audiences flock to How the West Was Won if it were done today?” Joyner asks. “I think they’d stampede.”

As far as epics go, Johnny D. Boggs wouldrather be watching Spartacus.