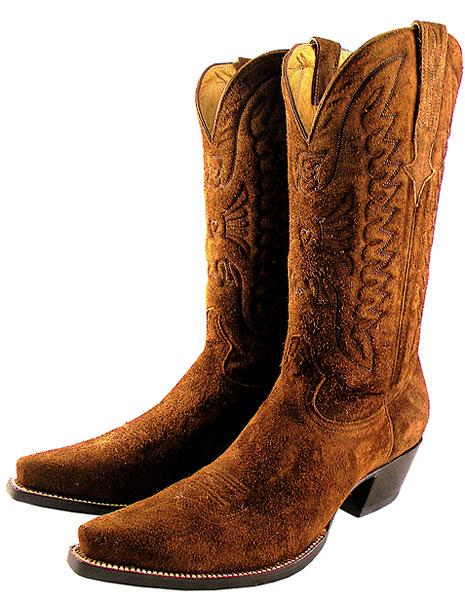

In rock ’n’ roll’s first across-the-charts hit, written on a paper bag in 1955 by Carl Perkins, the singer admonishes his dance partner not to step on his precious blue suede shoes. Sueded leather, whether it be blue, black or brown, is commonly made from split cowhide and is relatively fragile; it scuffs easily.

In rock ’n’ roll’s first across-the-charts hit, written on a paper bag in 1955 by Carl Perkins, the singer admonishes his dance partner not to step on his precious blue suede shoes. Sueded leather, whether it be blue, black or brown, is commonly made from split cowhide and is relatively fragile; it scuffs easily.

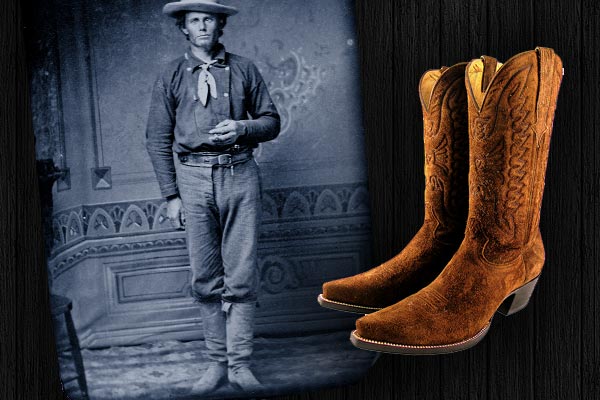

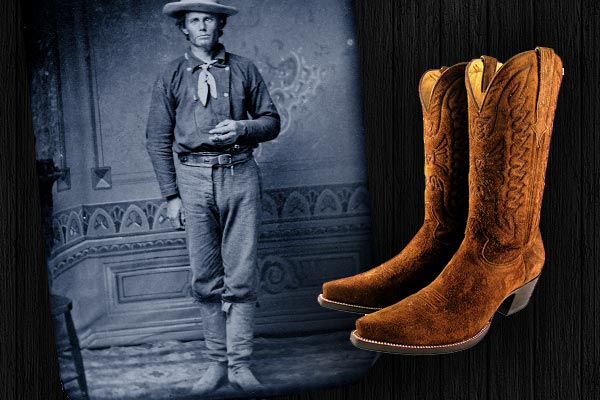

Given suede’s frail nature, folks might be surprised to see rustler Dan Dedrick wearing what appear to be sueded leather boots in the photo at left. More likely, Dedrick, Billy the Kid’s friend during and after the Lincoln County War in New Mexico, wore boots made from roughout leather. Roughouts are full-grain cowhide with the rough, textured underside of the flesh showing. Bootmakers did this with poor quality—and less expensive—leather

to hide problems on the smooth side of the hide.

Frontiersmen needed tough, durable boots that were impervious to thorns and stickers, and resistant to snake bites. They needed boots that didn’t fall apart when wet, a problem encountered by those who wore the shoddy surplus military-issue boots available after the Civil War. The most common style was an American version of the Wellington, the mid-calf, round-toed boot with a low heel favored by the British general who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815: Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington.

The American version of the Wellington was taller—almost to the knee. The upper parts were two pieces of leather, with the front piece

stretched and shaped to cover the front of the foot and toes. Dedrick’s boots fall in this category.

The most popular leather used to make these boots was full-grain cowhide waxed on the grain, or outer, side to repel water, mud and other offenses to leather. By and large, early Westerners wore boots made of plain leather that could take a lot of abuse and required little care.

Stitching on cowboy boots began to appear as the 1800s came to a close. The cobblers who made and repaired boots discovered that stitching on the shaft reinforced the leather and prevented it from collapsing and wrinkling like the boots worn by Dedrick. They also found that rows of stitching across the top of the vamp, where the foot branches into toes, allowed the boot to flex more easily. This, in turn, increased the life of the leather at this critical spot. Once bootmakers started stitching, they began to get artistic and produced elaborate designs on the shafts and vamps.

While cowboy boots made with exotic skins and flamboyant designs get the most attention, unadorned boots are the boots we work and play in. We tend to keep our plain cowboy boots because they get more comfortable the longer we wear them—just like the jeans we wear with them.

Don’t dismiss or feel sorry for the plain cowboy boot. It still has built-in elegance and a colorful pedigree. Even the most modest boots, like Dan Dedrick’s roughouts, have a little flair for flare that naturally puts some swagger in the step of its wearer. It’s a cowboy boot; you don’t care if it gets a little scuffed.

G. Daniel DeWeese coauthored the book Western Shirts: A Classic American Fashion. Ranch-raised near the Black Hills in South Dakota, Dan has written about Western apparel and riding equipment for 30 years.