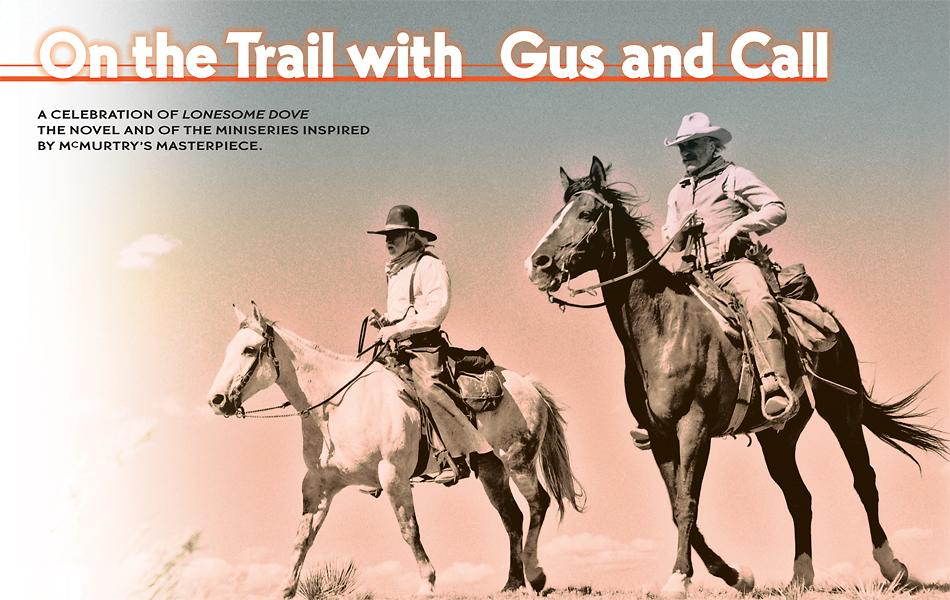

When Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove was published in 1985, virtually every review included the term “epic.” “Deeply affecting” was a close second in the flow of praise for what one critic called “the Great Cowboy Novel.”

When Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove was published in 1985, virtually every review included the term “epic.” “Deeply affecting” was a close second in the flow of praise for what one critic called “the Great Cowboy Novel.”

Its critical success was capped with the Pulitzer Prize and its mass popularity with a television miniseries graced by a rare combination of fine acting and high ratings. By then, Lonesome Dove was being called a Western classic. And it is, although not for reasons that would gladden every fan of Louis L’Amour and Zane Gray.

Lonesome Dove is most impressive as a literary balancing act. Its characters are comfortably familiar sorts who suddenly do the unexpected—and who always speak with the most wonderfully original blather. The story moves languidly for long stretches, then suddenly ignites in gun battles, stampedes, and gut cuttings to satisfy the most demanding action fan. Above all, for history students, McMurtry keeps Lonesome Dove centered between myth and anti-myth.

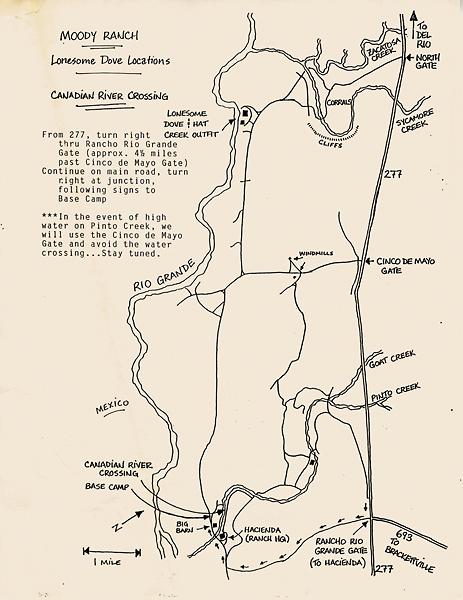

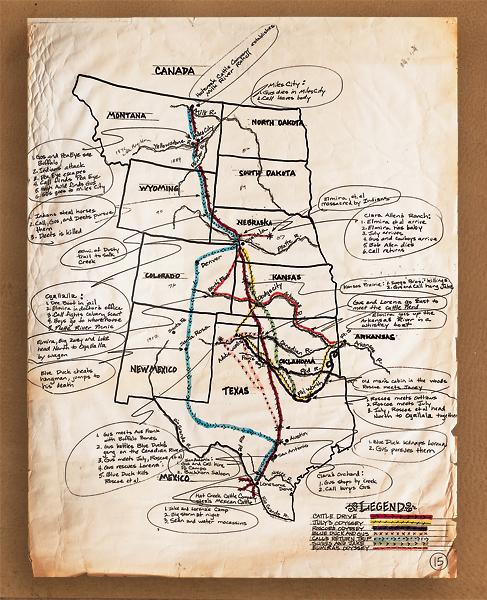

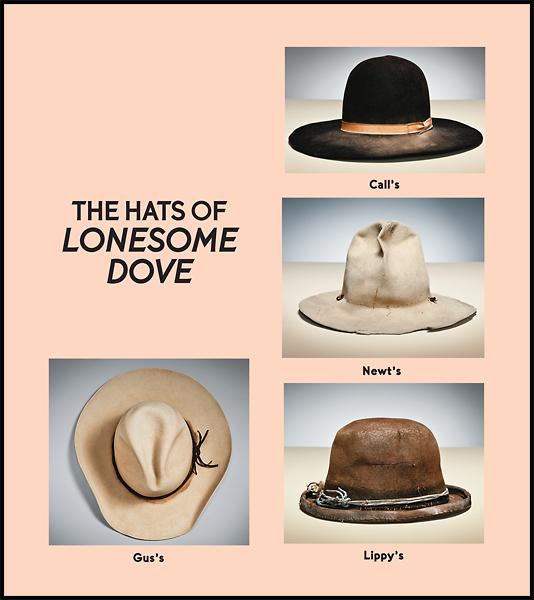

The story begins in the late 1870s in Lonesome Dove, a sunbaked speck of a town on the Texas-Mexico border. The turmoil during and immediately after the Civil War has subsided, and with it the need for aging former Texas Ranger captains like the book’s two primary figures, Woodrow Call and Augustus McCrae. With Pea Eye, Deets, Lippy, and others in the Hat Creek Cattle Company, they pass time in and around the town’s one saloon, the Dry Bean, where the prostitute Lorena conducts her business. Enter the handsome Jake Spoon, another ex-Ranger, who persuades the restless Call to drive a herd of three thousand cattle northward twelve hundred miles to the grassy valley of Montana’s Yellowstone River, nearly to the Canadian border. The long drive and its adventures consume most of Lonesome Dove.

For readers after historical accuracy, Lonesome Dove is mostly accurate, at least in the term’s narrowest sense. There are a few anachronisms and startling omissions. The Indians who send Gus to his deathbed with a rotting leg are presumably Blackfeet, who in fact were mostly in Canada by this time or starving on what remains today one of America’s bleakest reservations. It’s hard to imagine that the Hat Creek outfit sees no farmers; in western Kansas alone, sixteen counties were created during the 1870s, with more land broken to the plow than would have fit into Connecticut and Delaware combined. And where are the railroads? Every historical development in the novel’s background—cattle trailing and ranching, buffalo hunting, and the Indian wars—was either spun off directly or facilitated by the first transcontinentals built during the previous decade. Montana-bound drovers would have crossed three major lines. Various characters in the novel pass time in Dodge City, Ogallala, and Miles City, towns that were creatures respectively of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe; the Union Pacific; and the Northern Pacific. Except for some Mexicans and Irish, there is not much in Lonesome Dove to suggest that the plains West was quite an immigrant stew. The percentage of foreign-born persons in the Montana McMurtry describes was twice that of New York.

Still, given the story he chooses to tell, McMurtry is faithful in both broad strokes and detail. He catches beautifully the feel of the plains at the moment, just after the national centennial, when power tipped finally and quickly from Indians to whites.

The novel gives us as well a true feeling for cowboying. Besides his own experience, McMurtry seems to have drawn heavily from two classics, Teddy Blue Abbott’s memoir, We Pointed Them North (1939), and an early instance of what would later be called a nonfiction novel, Andy Adams’s The Log of a Cowboy (1903), both of them accounts of similarly long cattle drives. McMurtry borrows some material directly from the historical record. Call’s moving epitaph to Deets after his friend is killed trying to return an Indian child is an almost exact transcription of the tribute by the Texas rancher Charles Goodnight to Bose Ikard, a former slave who was Goodnight’s most trusted hand. The pyschopath Blue Duck has elements of Charlie Bent—the mixed-blood son of the Cheyenne Owl Woman and the prominent trader William Bent, who preyed mercilessly on Colorado whites after the Sand Creek massacre—and perhaps of the Kiowa warrior Satanta (White Bear). Blue Duck’s death, “flying” out the third-floor courthouse window just before he is to be hanged, is a mimic of Satanta’s suicide by diving headfirst from the second floor of the Texas state prison hospital in 1878.

McMurtry chose the cowboy’s West for his setting partly because that place and story are his and his family’s. Late in the nineteenth century, his grandparents took up ranching near the North Texas town of Archer City, where McMurtry lived and worked until leaving for Rice University. He heard the stories and absorbed, but didn’t share, his father’s longing to have worked the country at the time of the cattle drives. McMurtry has commented that he was moved to write Lonesome Dove partly by the “thrill of the vernacular,” the desire to re-create the speech and the dailiness of life among plainsmen of his grandfather’s time.

Clearly, however, he is up to much more than that. Embedded in this novel is McMurtry’s vision of pioneering, of what people of his grandparents’ time found, or hoped to find, and of how they and their world changed each other. This makes Lonesome Dove a Western in both meanings of the term. It is a wonderfully entertaining set piece from the legendary terrain of the cattleman’s plains.

McMurtry’s West was a testing ground for courage, and this was the last time in our history when, for the cost of a ticket or a long hike down the road, you could break into country twice the size of Europe and move virtually unfettered and act without concern for any but the most immediate risks.

At the heart of the Western is that vision of cutting loose from the settled to the wild, of shaping new country to the individual will. Whether we should be ashamed or proud of that emotional force is another question. The point here is that the dream was truly there, and because as Americans we instinctively recognize it, it continues to give Westerns an undeniable power.

And that in turn makes Westerns ultimately tragic. Whatever reality the dream held, the end was bound to come. The transition from frontier to full settlement was not smooth and unrumpled; it was a painful jolt. In the cattleman’s West, the end came quickly. Longhorns were first driven to Kansas the year before Grant was elected. By the time he left office, ranching was shifting to the northern plains and the Indians were defeated. In another decade, barbed wire had mostly closed the open range and ranching had become a corporate enterprise. Twenty-five years, tops, and whatever true freedom had ever been there was fenced and mortgaged.

Lonesome Dove holds us with such a grip because we feel the dream in Call and Gus, and so we also feel the awful sadness as we watch it all slipping away. If a myth is a story we tell to say who we are, there is something in that telescoping of time, and in the longing for what is given and then snatched back, that speaks from the heart of the American experience. The variations run through our national library: Fitzgerald’s receding green light, Leatherstocking sent into exile from his beloved forest, and Steinbeck’s Okies taking the road to the golden land and getting their heads cracked in its orchards. McMurtry adds to this literature the long trek to Montana and Call’s return in an evening’s gathering dark to Lonesome Dove, where his house is full of rats and the Dry Bean has burned down.

Lonesome Dove, whatever its limits as a narrative of fact, manages something doubly remarkable as a novel within that mythic vein. In a tradition we have come to know as clichéd and austere, it charms us with a story with flesh and humor. Doing that, it causes us to see all the clearer the yearning, loss and illusion that sit at the heart of our spiritual history.

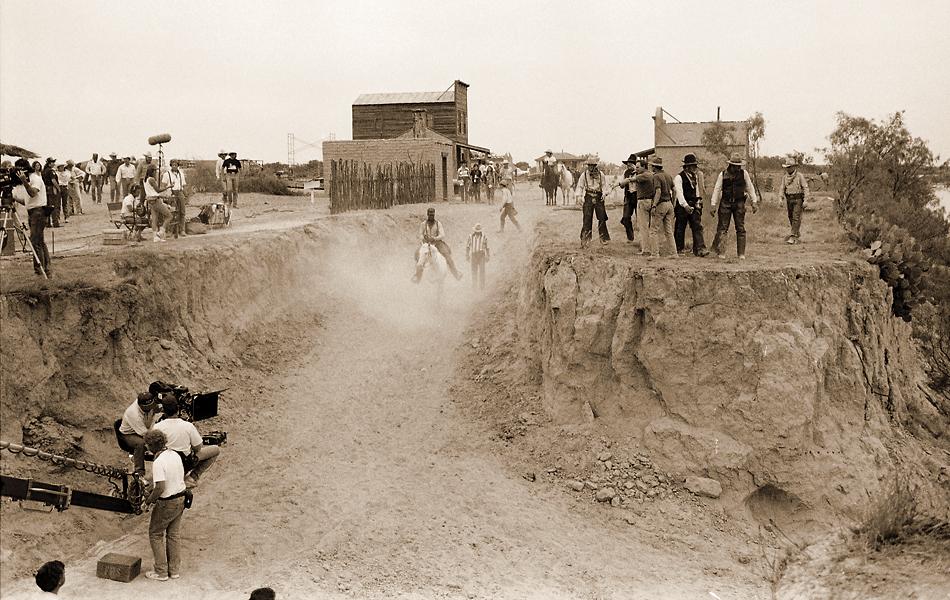

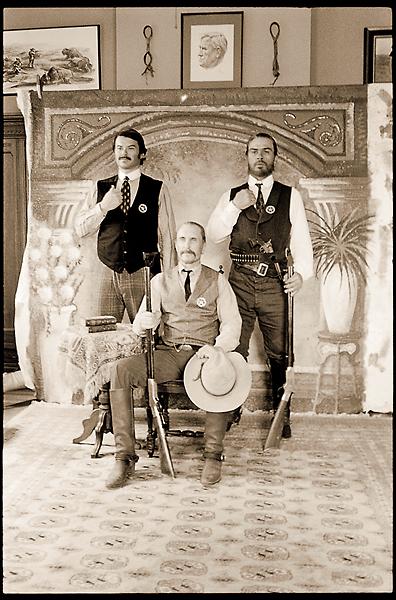

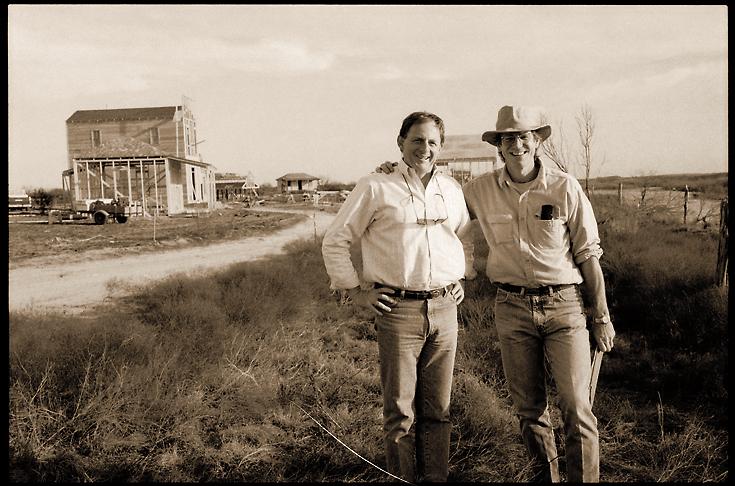

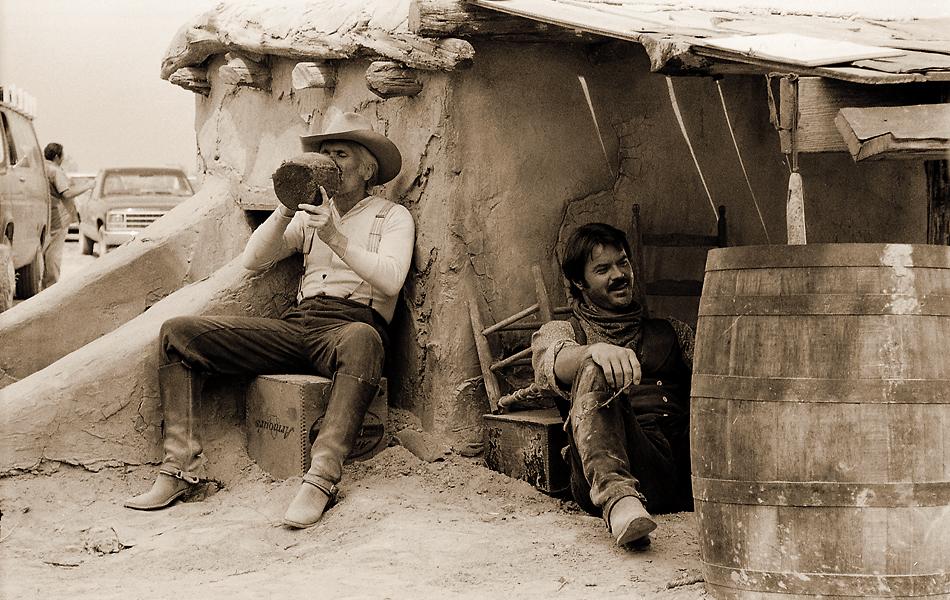

Photo Gallery

Photographs by Bill Wittliff