For decades, the Mandan people of the northern plains, whose vast and well-organized communities greeted French trappers and Lewis and Clark, were one of the first tribes described and illustrated in textbooks and histories of the West.

For decades, the Mandan people of the northern plains, whose vast and well-organized communities greeted French trappers and Lewis and Clark, were one of the first tribes described and illustrated in textbooks and histories of the West.

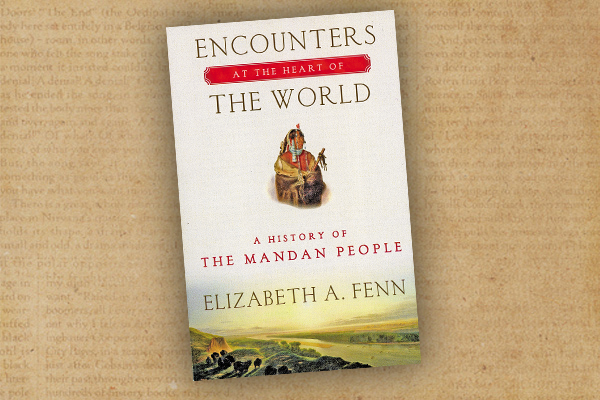

Yet, as the story of Westward expansion, Manifest Destiny and the post-Civil War settlement of the West continued through and into the 20th and now the 21st century, the Mandan, and their affiliated tribes, Hidatsa and Arikara, become anecdotal to the ongoing story: merely well remembered early subjects for artists George Catlin and Karl Bodmer. Colorado State University Associate Professor Elizabeth A. Fenn’s Encounters at the Heart of the World: A History of the Mandan People (Hill and Wang, $30) is her third and most ambitious book, in which she places the Mandan where they belong, back in the center of America’s courageous story of human resilience.

The primary strength of Fenn’s conclusions on the Mandan begins and ends with her extensive research, both in and out of the archives. Following a strong, current trend in Western history scholarship, Fenn’s research begins with a question that could only be answered through direct interaction with today’s descendants of the Upper Missouri River tribe—and a thorough firsthand knowledge of their traditional homelands in North Dakota. Fenn’s personal trek to the “heart of the world” at the confluence of the Heart and Missouri Rivers, to see the land and meet today’s living relatives of the Mandan who greeted Lewis and Clark, resolved her to tell their story.

The second reason Fenn’s scholarship is a model for current historians is her academic interest in the Mandans began with her earlier interdisciplinary research on the North American smallpox epidemic of 1775-82. “Reports of the smallpox in the upper-Missouri villages had intrigued me. How could it be, I wondered, that I knew almost nothing about this once-teeming hub of life on the plains?”

The Mandan were not exempt from the tragedy of unseen pathogens that were a scourge to the Indian peoples of the New World, and smallpox was one of the primary factors that led to the Mandan’s demise as a dominant plains culture. Fenn, though, reminds us that disease did not act alone in reducing the tribe’s influence and population: European technology (guns, ironware, trade goods) and two species of European animals forever transformed Great Plains economics, mobility and culture. First, the horse gave rise to the great, independent warrior nations of the Plains who were once relegated to nomadic dependency. Second, the Norway rat arrived by keelboat and destroyed the Mandan’s great stores of corn, which had given them their wealth and leverage with their trading partners. By the late 1830s, following the devastating smallpox outbreak of 1837-38, the Mandan peoples, who had numbered near 12,000 in 1450, were now less than 300.

Fenn’s modern recasting of the rise and fall of the Mandan culture from 1450 to 1850 does not leave the readers in the 19th century, but provides us with the hope of the present and the future for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara who still maintain their culture as a living metaphor for the resiliency of human beings at the heart of the world.

–Stuart Rosebrook