During the 1960s, when Philadelphia’s channel 48 ran Satan’s Satellites, I had no idea I was munching popcorn through a serial (Zombies of the Stratosphere) re-cut into a feature. I was jumping out of my pj’s because it was action-filled Sci-Fi, starring a jet-propelled hero, but I had never seen a chapter play. Featuring more fights and stunts than I had seen in a dozen programs, the story flew as fast as Rocket Man did, but something made it different.

During the 1960s, when Philadelphia’s channel 48 ran Satan’s Satellites, I had no idea I was munching popcorn through a serial (Zombies of the Stratosphere) re-cut into a feature. I was jumping out of my pj’s because it was action-filled Sci-Fi, starring a jet-propelled hero, but I had never seen a chapter play. Featuring more fights and stunts than I had seen in a dozen programs, the story flew as fast as Rocket Man did, but something made it different.

This Republic picture was made for me.

Ten years old and devouring Famous Monsters of Filmland every month, I would mull over its pages filled with images of heroes, baddies and monsters from serials of the 1930s and ’40s: The Crimson Ghost, Flash Gordon and, most intriguing, Gene Autry slugging a robot.

The problem: How could I see these serials? Answer: I couldn’t.

At the time, serials were rotting in studio vaults. The 13- to 20-minute length of each episode made serial chapters unsuitable for TV.

After Columbia Pictures produced its last serial in 1956, Blazing the Overland Trail, the form tumbled into a premature grave. Who needed serials, when we had TV? That was what studios thought, even if the belief didn’t compute. The chapter play has been with us since the beginning of film, designed to bring customers flooding back to each new attraction. Who wasn’t going to race to the theater to see if the heroine got off the ice floe or the hero survived the dynamiting of the gold mine?

No other movie form employed the “cliffhanger” structure, leaving the Saturday Matinee gang breathless for more as the credits rolled; what was going to happen next week was the talk of the schoolyard. Serials weren’t for the adults; they were for us kids.

The parents could take in William Powell and Norma Shearer, and the kids could revel in Buck Jones. By the dawn of sound, the serial had become the province of budget studios and poverty row independents. Outfits like Principal or Victory would snag a Hoot Gibson, put him through grueling paces for 10 days, butcher it together and have a new Western chapter play.

In the early 1930s, Universal was the serial leader at the studio level, racking up big dollars. Producer Nat Levine wanted a piece of that market. Levine’s scruffy Mascot Pictures was a half-a-rung up from poverty row, spending for star talent (Bela Lugosi, a non-Western John Wayne), while being tight with production.

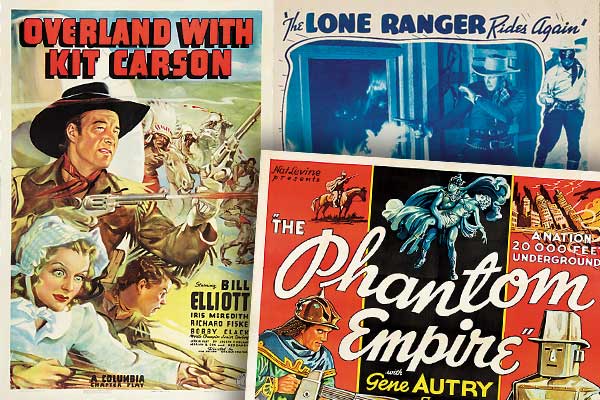

The Mascot Pictures’ logo signaled the end of my decade-long hunt for Autry and the robot when I finally saw The Phantom Empire. It was another condensed feature, with sound so low you couldn’t hear Autry’s singing between trips to the underground civilization of Murania, where he, and teenager Frankie Darro, battled an alien army determined to conquer the earth.

Autry’s only serial was a hit, allowing Mascot to merge with several low budget companies to become “B” factory, and serial powerhouse, Republic Pictures. Republic took the best of Mascot’s formula for action and added its own polish to produce a remarkably slick product for little money. Serial expert Eric Hoffman writes, “If you wanted exciting, sometimes breathtaking action by the best stunt people in the business, then Republic was the studio.”

Universal met the competition head on, with Columbia also entering the serial arena. For nine years, the three battled it out, drawing on radio shows, comic books and pulps for subjects. Even as Green Hornet, Captain Marvel and Spy Smasher blasted through their chapters, two-fisted cowboys were still the most popular with the front row kids.

Hoffman does add a note of caution: “These were done on tight shooting schedules, with budgets of several hundred thousand dollars, and less. How enjoyable each Western serial was depended on the studio and how much effort was put into production.”

Hoffman’s point is well taken; of the more than 60 Western serials produced between 1931-56, they’re not all lost treasures, but many do rise above their restrictions, as slick, remarkably entertaining, unpretentious examples of action-adventure filmmaking.

Thanks to companies like Alpha Video, Serial Squadron and VCI Entertainment, found on the Internet, the best of the chapter plays can be rediscovered and properly appreciated. Here are a few:

Zorro’s Fighting Legion: This 1939 Republic serial is one of the best, thanks to William Witney’s direction and Yakima Canutt’s stuntwork. Canutt repeats his famous Stagecoach drop between the running horses here, but since he’s not doubling anyone, the camera is closer, and we get to see the amazing stunt in all its glory.

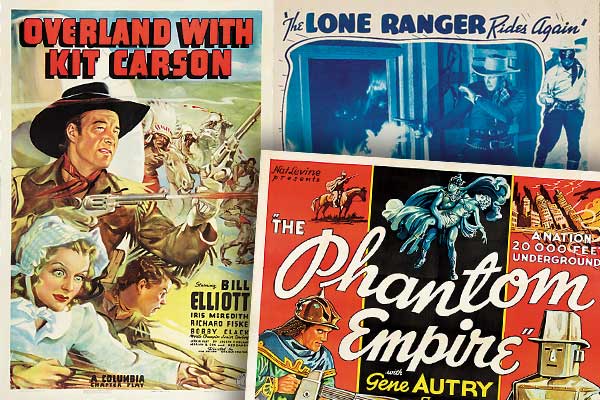

Overland with Kit Carson: “Wild” Bill Elliot personifies the kiddie matinee Western hero in this 1939 Columbia serial that shows none of the studio’s normal threadbare approach to its chapter plays.

Overland Mail: From Universal and starring Lon Chaney Jr., this 1942 serial features the classic “white polecats” disguised as Indians plot, but done with speed and polish. Castle Films released a nine-minute version titled The Indian Raiders for home use in 1956.

The Lone Ranger Rides Again: The second of Republic’s “Lone Ranger” serials, starring Robert Livingston as the masked one, shows the studio and Director William Witney at the top of their form. Chief Thundercloud plays Tonto in the 1939 serial.

Riders of Death Valley: Universal’s “Million Dollar Serial” with an all-star cast—Dick Foran, Charles Bickford, Buck Jones, Lon Chaney Jr., Noah Beery Jr., Leo Carrillo and more—double-crosses and chases more than most kids could handle. This 1941 chapter play is absolutely Universal’s best Western serial, and, despite an awful theme song, it is my personal favorite of them all.

C. Courtney Joyner is a screenwriter and director with more than 25 produced movies to his credit. He is the author of The Westerners: Interviews with Actors, Directors and Writers.