Born into a prominent New York family on July 27, 1840, Ranald Slidell Mackenzie was destined to live his life seated in a McClellan saddle on the back of an Army horse—and trail the painful growth of his nation through two major wars.

Born into a prominent New York family on July 27, 1840, Ranald Slidell Mackenzie was destined to live his life seated in a McClellan saddle on the back of an Army horse—and trail the painful growth of his nation through two major wars.

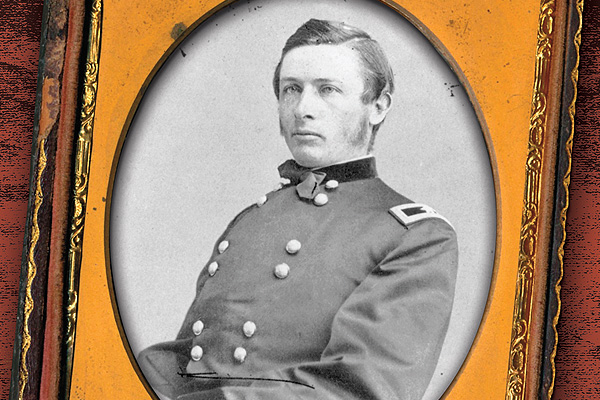

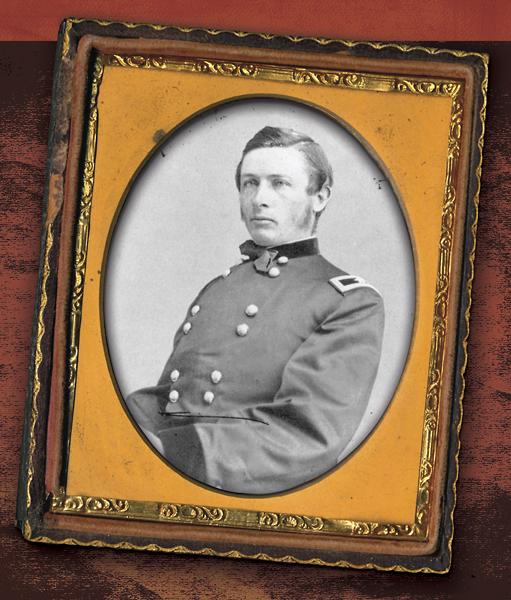

The son and brother of distinguished naval officers, Mackenzie chose his own path for a military career. He graduated at the head of his West Point class in 1862, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army of the Potomac. He quickly witnessed the carnage of eight battles, losing two fingers at the battle of Jerusalem Plank Road, earning the nickname “Bad Hand.” By the end of the war, he had reached the brevet rank of major general.

But it was the subsequent Western Indian Wars where Mackenzie would enforce the nation’s doctrine of Manifest Destiny, especially against the Comanches.

After the Civil War, Mackenzie was sent west to Texas to challenge the greatly feared Comanches for control of the Southern Plains. He was a U.S. commander whom President Ulysses S. Grant referred to as the “most promising young man in the Army,” while his soldiers nicknamed him the “Perpetual Punisher.”

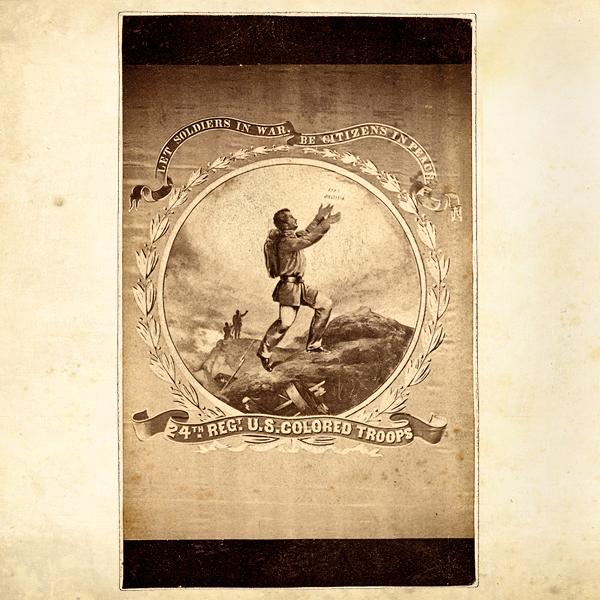

Promoted in 1867 to colonel of the Buffalo Soldiers’ 41st U.S. Infantry, which two years later became the famous 24th U.S. Infantry, he began leading expeditions against tribes across Texas and into Mexico. His mission: forcing the Indians to live on their reservations, particularly the Comanches. In 1871, Mackenzie, now assigned the 4th U.S. Cavalry, was unleashed from Fort Richardson in Jacksboro, Texas. His directive was to destroy and relocate the Comanches back to Fort Sill in Oklahoma Territory. He proved himself the era’s most effective Indian fighter at the Battle of Blanco Canyon and the Battle of North Fork on the Texas plains of the unforgiving Llano Estacado.

One of his most infamous punitive raids happened September 28, 1874, when he led forces 1,000 feet into Palo Duro Canyon on an Indian trail so steep that soldiers had to lead their horses single file. Instead of following the fleeing Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, Mackenzie captured and killed 1,500 to 2,000 of their horses, ponies and mules. Left horseless and starving, unable to hunt, the tribes all returned to the reservation by February 1875.

War takes a toll on young officers. By 1883, physically wounded seven times, 43 years of age, Brig. Gen. Mackenzie now suffered psychological wounds, losing his mind, some attribute to a severe fall from a wagon at Fort Sill in Oklahoma Territory. He was returned to his native New York, committed to an asylum, and retired from the Army. The general died at his sister’s home on January 19, 1889, and was interred in West Point Cemetery.

Photo Gallery

– all photos Courtesy Library of Congress –