No man is an island, isolated from his time and place, so exploring the world of a historical individual not only gives a sense of reality to his story—it can tell us things about his character we might have missed in a more targeted search.

No man is an island, isolated from his time and place, so exploring the world of a historical individual not only gives a sense of reality to his story—it can tell us things about his character we might have missed in a more targeted search.

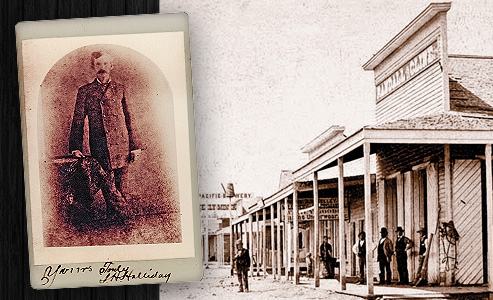

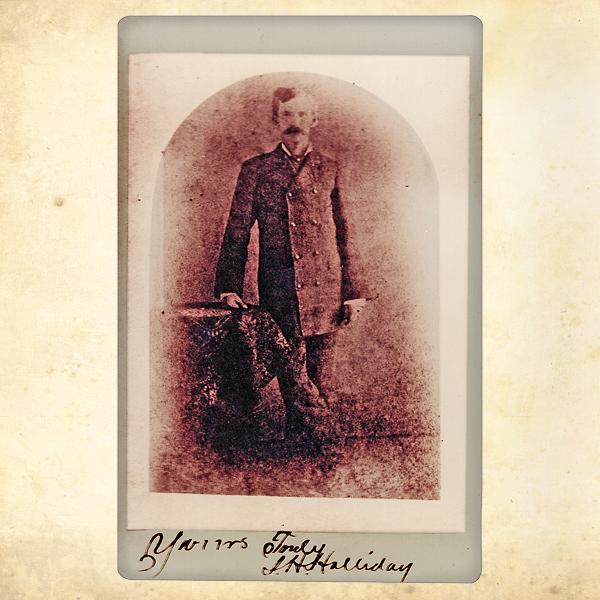

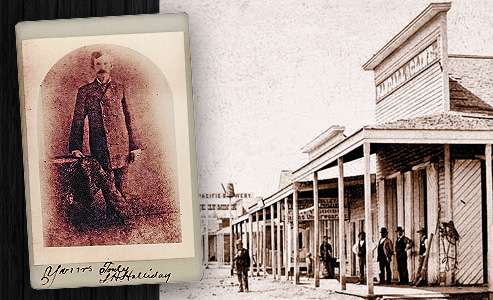

Take my study of Doc Holliday. While researching his dental school days in Philadelphia, I dug into the history of the city in the 1870s and explored the lives of his classmates at the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery. One student became intriguing. His name was Auguste Jameson Fuches, the son of French-born immigrants who had settled in St. Louis, Missouri.

Fuches was mentored by the famous Dr. Homer Judd, who had pioneered the use of Greek nomenclature for the dentition. Dr. Judd helped establish a dental school in St. Louis (present-day Washington University School of Dentistry) where Fuches studied before continuing his education in Philadelphia. After dental school, Fuches returned to St. Louis to practice dentistry, then went back to Philadelphia to receive a second degree in medicine.

That was the caliber of student with whom young John Henry Holliday had associated in his two years of college, which tells us something of the kind of life he lived while there—study, practice, more study. But I learned another interesting bit of information while getting to know Fuches—his address in St. Louis: Fourth Street, near the Planters’ House hotel.

That was an address which surprised me, being the same mentioned by Kate Elder when she claimed that she had first met Holliday when he was practicing dentistry in St. Louis, “on 4th st near the Planters Hotel.”

Elder’s recollections appeared in a letter to Brewery Gulch Gazette writer Anton Mazzanovich, but were mostly discredited as the rantings of a frontier whore who wanted some of the celebrity of the recently published Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal. Now here was Holliday’s classmate with the same address, giving us cause to believe at least some of what Elder said—and to look into the possibility that Holliday himself spent some time in St. Louis after finishing his dental education. It was a discovery that changed our understanding of his history.

This same type of exploration led to discoveries about Holliday in Prescott, Arizona, where he and the Earps laid over on their way to Tombstone. Virgil Earp had gone to Prescott first, in the summer of 1877, operating a sawmill in the shadow of Thumb Butte. Wyatt Earp and family, with Holliday and his mistress in tow, arrived by wagon train in the fall of 1879. Virgil and Wyatt headed to Tombstone, but Holliday chose to stay in Prescott, the territorial capital at the time, a pine-scented mining camp in the cool highlands of northern Arizona. With a strip of saloons and gambling halls gaining fame as Whiskey Row, it was a perfect place for a sporting man like Holliday and his mistress, Elder, to take up residence.

Except that Whiskey Row wasn’t Holliday’s place of residence in Prescott, and Elder wasn’t his roommate. She had left him soon after their arrival, going off to try her luck in the mining camp of Globe, and he moved into a boarding house a few blocks up from Whiskey Row. This time, the surprises in Holliday’s story come from his neighbors in and around the boarding house.

His landlord in Prescott was Richard Elliott, one of the owners of the Accidental Mine on Lynx Creek. The other occupant of the Elliott house was miner and stockman John J. Gosper—who also happened to be secretary of Arizona Territory and acting governor in the absence of the great explorer-turned-politician John C. Frémont.

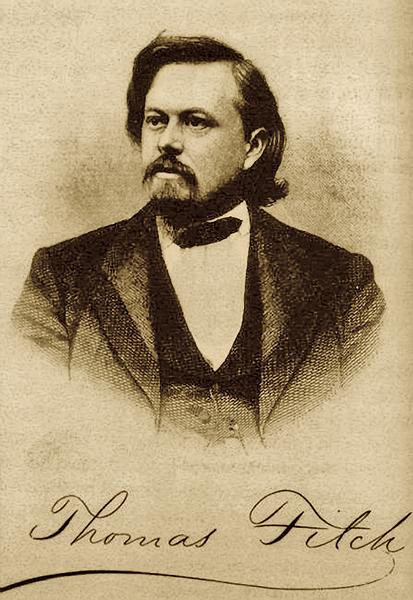

Next door to the Elliott house was the home of William Mansfield Buffum and his family. Buffum was a California businessman who had come to Arizona in the early days of the territory, settling in Prescott and establishing a prosperous mercantile company. His wife, Rebecca Evans Buffum, was known for her dinner parties—her china is now on display at the Sharlot Hall Museum in Prescott. Some of those dinner parties were no doubt attended by Buffum’s friend and former member of the Territorial Legislature, Thomas Fitch.

Fitch was one of the brightest legal minds in the Western territories—a lawyer, actor, orator, novelist and newspaper editor who had worked with Mark Twain in Virginia City, Nevada. He had been a district attorney and a delegate to the Nevada State Constitutional Convention, and he had helped draft the Utah State Constitution. Although not a Latter-day Saint, he had served as general counsel to the Mormon Church and defended church leader Brigham Young during the polygamy trials. He witnessed the laying of the first rail at the western terminus of the Overland Route in Sacramento, California, and the last one at Promontory Summit in Utah.

Those were Holliday’s influential neighbors at a most interesting time in Arizona history. Down on the southern border of the territory, near the mining town of Tombstone, American cowboys were crossing the U.S.-Mexico border into Sonora, stealing Mexican cattle and rebranding them to sell to U.S.

military bases, and sometimes killing Mexican citizens.

Mexico’s government sent a series of angry communiqués to Washington, D.C. demanding an end to the depredations, but the federal government, operating under the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, claimed the border was Arizona’s problem and the Territorial Legislature should handle the trouble. The territory disagreed, saying the federal border was Washington, D.C.’s responsibility, and refused to allocate funds for a police action, leaving the situation a stalemate.

But when Mexico threatened a war over the border issues and Washington, D.C. ordered the Arizona Territory to quell the situation, Gov. Frémont proposed a plan authorizing U.S. Marshal Crawley P. Dake to appoint special deputies to hunt down the rustlers (Dake appointed Virgil as one for Tombstone, in November 1879). Then the governor left Arizona, putting Acting Gov. Gosper in charge of enforcing the plan.

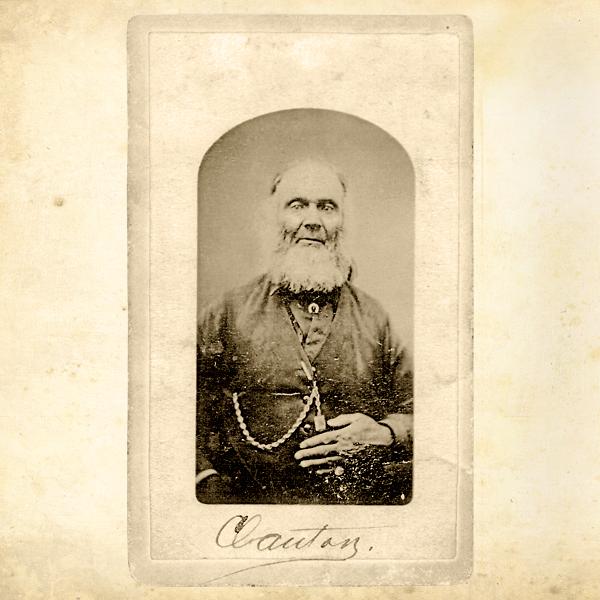

That was the lay of the land when Holliday left Prescott for Tombstone and arrived in September 1880; he soon became personally involved in the border troubles. After a massacre of Mexicans by cowboys near Fronteras (in the northeast of the Mexican state of Sonora) in May 1881 and another at Skeleton Canyon (northeast of the Arizona town of Douglas) in July 1881, Holliday’s former roommate Gosper decided to “take action.” Gosper’s private correspondence does not specifically state that “action,” but within weeks, the bloody Guadalupe Canyon Massacre occurred on August 13, 1881, in which several rustlers

were killed—including rustler boss Old Man Clanton.

The rumors at the time suggested that Wyatt and Holliday had somehow been involved. Holliday later said of the reasons behind the O.K. Corral gunfight that he and the Earps had “hunted the rustlers, and they all hate us.” He wasn’t referring to the Vendetta Ride that came after the October 26, 1881, gunfight, but to an event that had occurred before.

Did the Guadalupe Canyon Massacre have something to do with Gosper’s plan of “action” to stop the rustlers and stave off a war with Mexico? Had he followed Gov. Frémont’s lead of assigning deputies, but in vigilante fashion?

Gosper admitted to encouraging the formation of a “Committee of Safety” in Tombstone, to protect life and property, but he denied that the group was formed so its members could take the “law into their own hands.”

Yet Gosper was no stranger to employing vigilante means under the legal power afforded him, as shown in an 1879 directive from his office in Prescott: “…I, John J. Gosper, Acting Governor of the Territory of Arizona, do hereby authorize the payment out of the Territorial Treasury, the sum of $500 to any individual who shall kill, by means of fire arms, or otherwise, the highway robber while in the act or attempt of robbing the mail or express, or search of the passengers….”

Perhaps he tried the same tactic to rid the country of cowboys, as well, which would explain much about the trouble in Tombstone. It also might explain a surprising addition to the Earp-Holliday defense team at the O.K. Corral hearing—attorney Fitch from Prescott, bringing a $10,000 bond along with him.

As Holliday said of his time in Arizona, “The claim that I make is that some few of us pioneers are entitled to credit for what we have done. We have been the forerunners of government. As soon as law and order were established anywhere we never had any trouble. If it hadn’t been for me and a few like me there never would have been any government in some of these towns. When I have done any shooting it has always been with this in view.”

Sounds like the Gunfight Behind the O.K. Corral was a great deal more than a street fight or a bounty hunting deal gone bad, as it appears Holliday may have known about the cowboy situation in southern Arizona even before he arrived in Tombstone.

When one looks beyond Holliday himself to the men he knew, his story grows—and sometimes our understanding of history grows, as well.

To get the entire story, read The Last Decision, the final volume of “Southern Son: The Saga of Doc Holliday,” coming May 2015. After helping save the antebellum home of Holliday’s uncle in Fayetteville, Georgia, Victoria Wilcox spent 18 years researching the life of Holliday to write a historical novel trilogy. The first two volumes, Inheritance and Gone West, are in bookstores now.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– by bob boze bell –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Victoria Wilcox –