Following Geronimo’s third and final breakout from the White Mountain Apache reservation in May 1885, first Gen. George Crook, then Gen. Nelson A. Miles sought to capture or kill him and his people in the rugged, mountainous country of Sonora.

Following Geronimo’s third and final breakout from the White Mountain Apache reservation in May 1885, first Gen. George Crook, then Gen. Nelson A. Miles sought to capture or kill him and his people in the rugged, mountainous country of Sonora.

The campaigns lasted more than a year. In August 1886, at Miles’s order, Lt. Charles B. Gatewood succeeded in putting two Apache scouts, Kayitah and Martine, in touch with Geronimo and his compatriot, Naiche, son of Cochise. They persuaded them to talk with Lt. Gatewood, talks that led to Geronimo’s agreement to accompany Capt. Henry W. Lawton north to Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, and talk with Gen. Miles about surrender.

The Apaches and Lawton’s command reached their destination on the afternoon of September 2, 1886. Skeleton Canyon opened on the west side of the Peloncillo Mountains. Venturing into the narrow entrance, the Apaches noted that it widened and divided into two branches. But they also noted that several army units had already bivouacked, and more arrived before they could go into camp.

The numerous soldiers, together with the many couriers who came and went, made all the Chiricahuas more nervous and suspicious than they already were. They informed Lawton they would move deeper into the canyon and camp alone. Like Crook at Canyon de los Embudos, the absence of Gen. Miles further upset them.

With his usual acute eye for topography, Geronimo selected a plateau at the confluence of the two canyons. From here they could watch the soldiers below and scan the San Bernardino Valley beyond, as well as defend themselves if it became necessary. Gatewood and interpreter George Wratten stayed with them.

The agitation persisted through the night and into September 3. Finally, from their elevated perch, the Apaches sighted dust arising from the approach of vehicles. They assumed that at last the general had come. They could talk with him and “look him in the eye.”

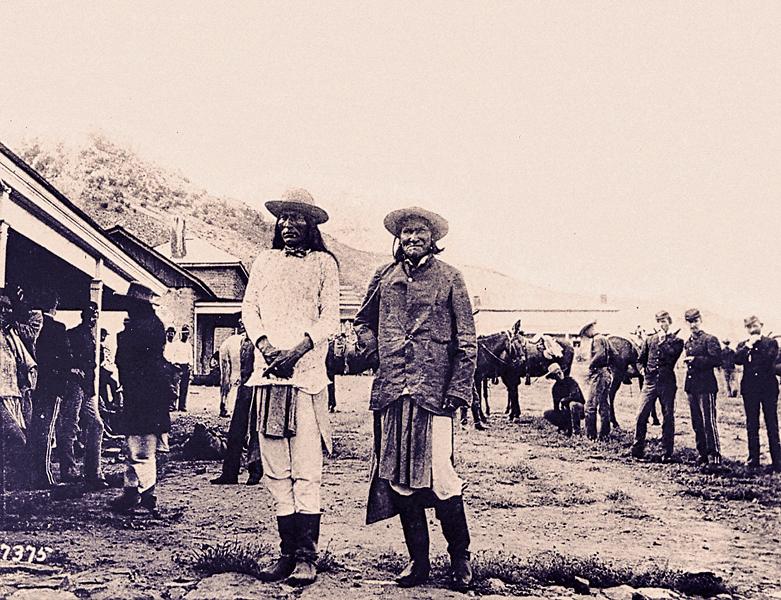

Geronimo pressed Gatewood to take him to meet Miles. Near the mouth of the canyon, the great Apache leader and the great American general stood face to face. It was a more dramatic and meaningful encounter than Geronimo’s with Crook at Canyon de los Embudos. For both Geronimo and Miles, the outcome would be momentous. It could mean Apache surrender, in the full sense of the word that Geronimo had never entertained, or an immediate exchange of fire between Apaches and soldiers, and a stampede of Apaches back to Mexico.

The two warily shook hands and then talked briefly. Gatewood, sitting to the rear, recalled that Miles simply told them to surrender and be sent to Florida to await the action of the president. Then Geronimo turned to Gatewood and said, “Good, you told the truth,” shook hands with Miles and declared he would go with him regardless of what the rest decided.

Naiche had not accompanied Geronimo nor decided to surrender. Naiche’s brother had gone to Mexico looking for a lost pony and perhaps been killed by Mexicans. Naiche had gone into the hills to mourn.

After meeting with Miles, Geronimo went in search of Naiche and persuaded him to meet the general. They met with him on the morning of September 4. Naiche remained suspicious of the good intentions of Miles, and he had not yet surrendered his following, which was much larger than Geronimo’s. Miles explained in more detail his plan for the Chiricahuas. Somewhat reassured and encouraged by Geronimo, Naiche surrendered his following. All laid down their arms.

According to Geronimo, Miles’s explanation took place before Naiche and the band as a whole had agreed to surrender or laid down their arms; only Geronimo himself had yielded. Dr. Leonard Wood and Lt. Thomas Clay were present. Miles said, “You go with me to Fort Bowie and at a certain time you will go to see your relatives in Florida.” He drew a line on the ground and said it represented the ocean. Placing a stone beside it, he said, “This represents the place where Chihuahua is with his band [Fort Marion, Florida].” He then picked up another stone and placed it a short distance from the first. “This represents you, Geronimo.” He then picked up a third stone and placed it a short distance from the others. “This represents the Indians at Camp Apache. The President wants to take you and put you with Chihuahua.” He moved the Geronimo stone, and then he moved the Camp Apache stone next to the Chihuahua stone. “That is what the President wants to do, get all of you all together.”

Accompanied in an army ambulance by Geronimo and Naiche and three men and a woman, Miles and Lt. Clay pushed forward on the morning of September 5, moving hastily to reach Fort Bowie the same day. Lawton followed with the rest of the Chiricahuas, traveling at a more leisurely pace. They arrived at the fort early on September 8.

While waiting at Fort Bowie, Miles again explained his idea of the future to Geronimo and Naiche. He said, “From now on we want to begin a new life.” He held up one of his hands with the palm open and marked lines across it with a finger of the other hand. “This represents the past; it is all covered with hollows and ridges.” He rubbed the other palm over it and said, “That represents the wiping out of the past, which will be considered smooth and forgotten.”

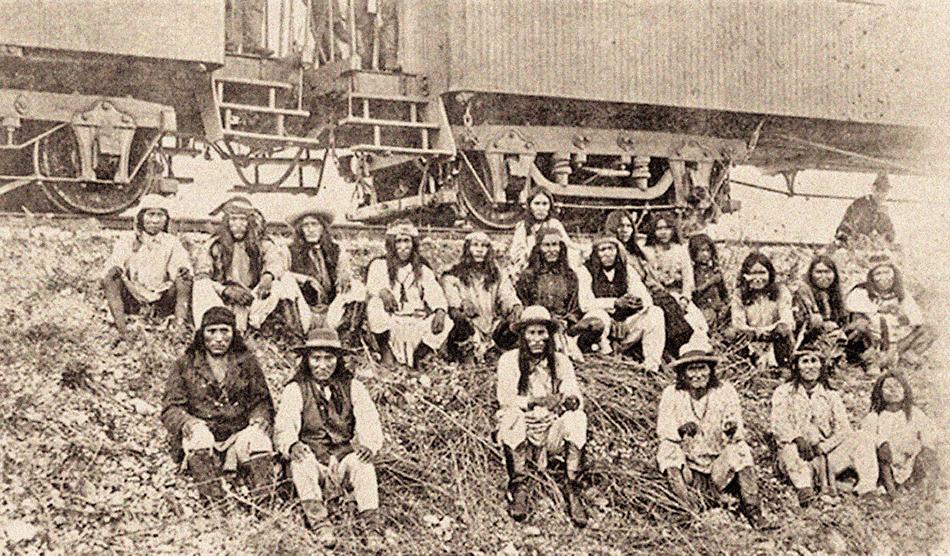

On the day Lawton arrived with the people, September 8, all were packed into wagons as the 4th Cavalry Band drew up on the parade ground and played “Auld Lang Syne.” The wagons moved north down the road to Bowie Station, where a train lay waiting.

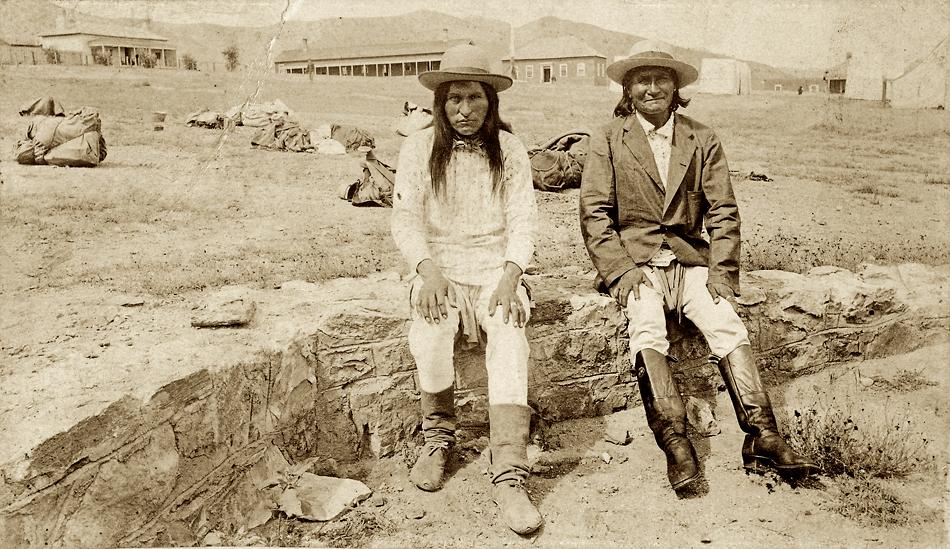

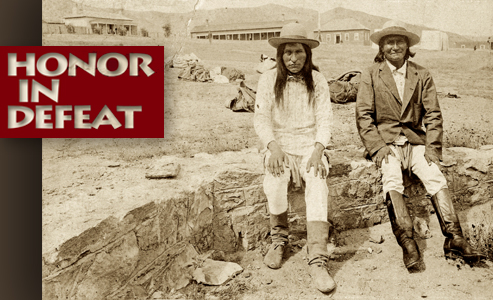

After a photographer took pictures, they boarded the cars—15 Chiricahua men (including Gatewood’s scouts Kayitah and Martine), nine women and three children, 27 in all. Captain Lawton took charge with an escort of 20 cavalrymen. Miles and his staff rode as far as the Rio Grande, in New Mexico, then changed trains for Albuquerque. The special train steamed on east, headed for Florida.

Although a man of periodic mood swings, Geronimo had provided exceptional leadership in the days following his extended discussions with Lt. Gatewood on the Bavispe River. He never relaxed his inbred suspicion, never let his guard down, remained always alert for treachery.

He forced the Mexican prefect, Jesus Aguirre, to back down and return to Mexico. He followed the wise counsel of Gatewood and appeared, or pretended, to accept Capt. Lawton as trustworthy. Traveling north to Skeleton Canyon in tandem with an American command posed dangers, as the murderous intent of Lt. Abiel Smith demonstrated, but Geronimo negotiated this journey with skill.

Naiche remained in the background, letting Geronimo plot the daily course of action. In the end, Geronimo probably had more influence than Miles in persuading Naiche to surrender his following.

When he met Gen. Miles on September 3, Geronimo discovered a general who did not “talk ugly” like Crook and gave in to him. Putting his trust in Miles proved a mistake with lifelong consequences. But by now, surrounded and outnumbered by troops, an attempt to break free would be costly and leave his people as destitute as ever. Besides, Miles seemed like a trustworthy man, and his talk about getting all the Chiricahuas together held strong appeal. Geronimo did not understand how little control Miles had over their future.

Geronimo had the good sense to recognize the truth of what Kayitah and Martine said when they finally met with him in Mexico. They described the pitiful condition of the Chiricahuas, which Geronimo could plainly see around him as the two emissaries talked.

Overcoming his stubborn reluctance to meet with soldiers, he consented to go down and talk with Lt. Gatewood. He had long known and trusted this officer. From this point forward, his strategy was to bargain for the best terms possible, ideally a return to the old life on the reservation. When this proved impossible, he held forth the prospect of continuing the war, but also gradually accepted the inevitable.

As a matter of fact, although raiding occurred repeatedly, only two clashes with the U.S. cavalry occurred during the last two years of Geronimo’s freedom, with only minor skirmishes. Occasionally his camp was seized by Apache scouts or soldiers, but not before Geronimo took alarm and scattered his people into the hills. The army and the scouts tried to find and destroy the Chiricahuas, without success. Geronimo and Naiche led their people through the tortuous Mexican defiles they knew so well and constantly eluded their pursuers. That in itself reflects creditably on Geronimo, whose avoidance of the enemy and subsistence of his people by raids on the Mexicans demonstrate superior leadership.

During the two-year period ending at Skeleton Canyon, Geronimo’s name appeared almost daily in the national press. That he became the best-known of all Indian leaders sprang largely from this two-year period. For vulnerable citizens in both Mexico and the United States, he personified the Apache menace. Ironically, despite the atrocities committed during raids on civilians, his fame grew not from war, but from his uncanny avoidance of war.

Although 1885-86 marked Geronimo’s preeminence as a war leader, his success in avoiding war and finally in working through the tortuous process of surrender marked his finest period as a fighting Apache.

This edited excerpt is from Geronimo, by Robert M. Utley and published by Yale University Press. The former National Park Service chief historian is the author of numerous history tomes and resides in Scottsdale, Arizona.