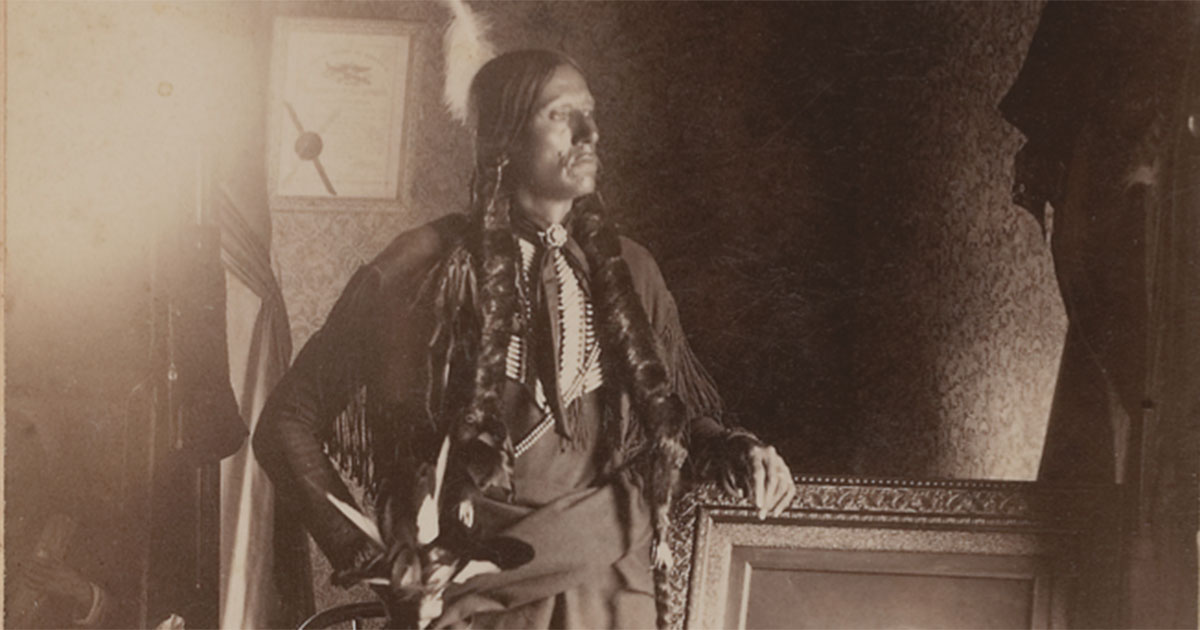

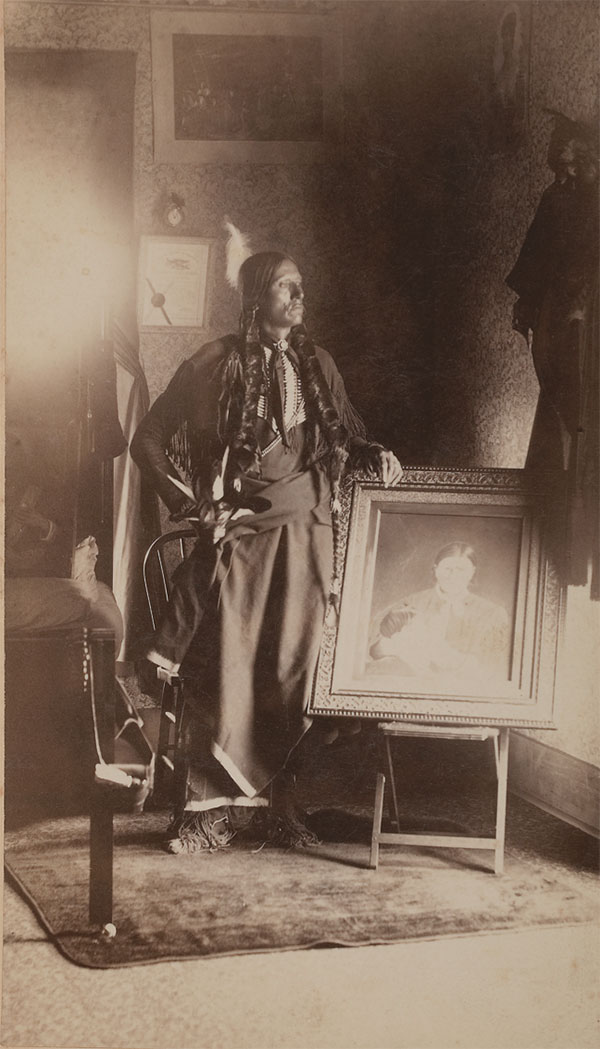

An Indian with his thick, long braids wrapped in otter fur stands beside an oil portrait of a woman and a baby.

Who was this man? What had happened to the people in the painting who were obviously important enough to the man that he wanted to be captured with them for time immemorial?

The size of a picture postcard, the photo of this Indian is an albumen print, which first came into being in 1850 and peaked in the 1860s-90s. Seeing the pencil markings “Leny. 1892,” you would at least know the true or approximate age of the photo. And if you had your trusty tome of Carl Mautz’s Biographies of Western Photographers, 1840-1900, you might figure out “Leny” could be photographer William J. Lenny. He partnered up with William L. Sawyers in Purcell, Oklahoma, to take photographs of the local Indians. Another marking “Comanche 196” would aid in identifying the man portrayed in the photograph.

The story behind the photo, though, is yet unknown to you, and that, combined with the visual impact of the image, is often what turns people into collectors of historical photographs.

That certainly was the case for Wes Cowan, who became fascinated with such photography while trolling antique shops as a graduate student at the University of Michigan in the 1970s. Over the course of 15 years, he would amass one of the best collections of Frank J. Haynes stereoviews and painfully part with it to start his own business—as an auctioneer. Today he is not only the owner of Cowan’s Auctions but also a celebrity, recognized by many as one of the appraisers featured on PBS’s Antiques Roadshow and as one of the sleuths who brings the true story of a collectible to light on History Detectives.

So what is the true story behind this photograph that hammered in at Cowan’s on December 9, 2009, for $3,500?

Since numerous photographs exist of this Comanche chief, anyone versed in Comanche history would have recognized this man as Quanah Parker.

Yet this is not merely a portrait of him; even a casual glance at this image may open one’s heart to the belief that an incredible story must lie behind this photo.

When Quanah left the photo gallery with his print in hand, he would return the portrait of the woman and child to a wall in his two-story home known as the Star House (its metal roof featured stars that mimicked those appearing on the uniforms of U.S. military officers). Located on the Comanche reservation near Fort Sill, Oklahoma, his home had been built in 1884, the same year that he ran an advertisement in The Fort Worth Daily Gazette, seeking a photograph he had heard existed of his mother Cynthia Ann Parker.

The daguerreian who had captured on film Cynthia Ann and her two-year-old daughter Prairie Flower in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1862 responded to the ad. “Mr. Corning has this daguerreotype, and says it is an excellent likeness of the woman as she looked then. It is now at the Academy of Art, Waco, and several photographs will be taken from it, one of which will be sent to the young Indian, who,” the May 26, 1884, edition of the Gazette could not resist adding, “ought to be thus convinced that it is a good thing to advertise in the Gazette.”

Quanah, the last chief of the Quahadi Comanche, finally possessed a permanent memento of his white mother who had been captured by the Comanche as a nine year old, raised by them and then recaptured by Texas Ranger L.S. Ross and his men in 1860 to be returned to her relatives—unhappily, if truth be told, as she missed her two sons she had been forced to leave behind, with Quanah as the eldest.

Over the past 15 years, Cowan’s has sold a number of portraits of Quanah Parker, yet auctioneer Wes Cowan admits to us, “of the Parker images I’ve handled, this is the most poignant, and most compelling.”

Even more special, the print not only speaks of a son’s undying love for his mother, but also captures the chief at a pivotal moment in his own life.

“Free grass, free soil, free speech, free lunch, free whiskey will make a platform for a free fight in Texas,” reported a pioneer paper in Dallas, Norton’s Intelligencer, in May 1884.

What actually happened was closer to how the Gazette reported the “free grass”* issue on May 16, 1884, “‘The time will never come in Texas,’ says Gov. Ireland, ‘when the cow shall not run on the commons….’”

Thanks largely to Quanah’s support of local Texas cattlemen such as Charles Goodnight and the Burnett family, the year 1884 brought about the first major lease of Comanche tribal lands for grazing rights. The chief would find himself caught between the anti-lease faction and those who sided with him that the Indians may as well make money off of any land they are not using. He’d dismiss the former to Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller in February 1885: “I cannot tell what objection they have to it, unless they have not got sense. They are kind of old fogy, on the wild road yet, unless they have not got brains enough to sabe [know] the advantage there is in it.”

The chasm would persist between his fellow Indians whom he characterized as “old fogy” and those who accepted the grass money. Parker would profit the most, not only materially, but also gaining respect and recognition among the whites and some of his fellows as the principal Comanche chief until his death in 1911.

Today, mother and son, who had been brought together much later in life via her image captured on a “mirror with a memory,” lie buried next to each other in Oklahoma’s Fort Sill Cemetery.

Many more such photographic treasures bid out at Cowan’s auction in December, which totaled more than $565,000. A few of the most interesting ones are presented here.

* “Free grass as used in state politics today applies to all uninclosed [sic] lands, public and private, and means that these lands shall remain rent free to stockmen,” reported The Fort Worth Daily Gazette on June 5, 1884.