Everyone’s heard the iconic children’s tale about the “little engine that could.” But few realize a real-life version exists.

Call it the “movie that saved a railroad” because that’s exactly what A Ticket to Tomahawk did for the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad that today is one of Colorado’s top tourist attractions.

Millions have traveled the breathtaking route into the San Juan Mountains on a train so popular that it’s hard to believe it once was old and tired and ready for the scrap yard. Then a California historian wrote a “delicious” screenplay and convinced producers to feature the old rail line. Marilyn Monroe was even cast in the film. But that’s getting ahead of the story.

Headed For Doom

The town of Durango, Colorado, was built by the Denver & Rio Grande Railway in 1880. Within two years, the railway already built the rail lines into the mountains to Silverton. Gold and silver were waiting to be shipped down that line—some say $300 million in precious metals rode those rails—yet the route was so beautiful that from the very beginning, passengers were encouraged.

But by 1893, silver prices dropped from $1.05 an ounce to just 63 cents an ounce. Ten large mines in the Silverton district closed. A few years later, a couple other mines played out. That wasn’t the only disaster. A fire in 1889 had already pretty much destroyed downtown Durango.

Life in Durango only got worse, and money never again was plentiful. Rock slides and floods caused problems. The “war to end all wars,” WWI, came along, and the military ran the railroad for its own needs. The end of the war didn’t end the misery. The Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 killed 10 percent of Silverton’s population in just six weeks. More mines closed and finally, the railroad stopped operating completely. It would stay silent for a decade.

Then came WWII, and the government reopened the smelter in Durango to process, not silver, but uranium. The government operated the smelter into the late 1940s, but when that use ended, the railroad was again in danger of disappearing. In 1948, serious plans were entertained to sell off the rails and locomotives for scrap.

A small staff struggled along, trying to salvage the line as a tourist attraction, but their efforts looked doomed. Thankfully, Hollywood discovered this precious piece of Colorado and gave the world A Ticket to Tomahawk.

Flash of Genius

Screenwriter Mary Anita Loos hatched the idea for A Ticket to Tomahawk in her beautiful historic hacienda in Santa Monica, California—today the site of La Senora Research Institute. She was fascinated by a narrow gauge model train engine that she and her first husband, Richard Sale, had bought. If she could write movies like her Comedy Western about two Easterners seeking their fortune from a gold mine that was discovered by a father who was murdered for it (1948’s The Dude Goes West), “Why not a story about the little narrow-gauge tracks that did so much to open up the West?” she told the Durango Herald-Democrat in 1949.

“We did a lot of research and looked at all of the narrow gauge trains. But the incredible Animas Canyon was the deciding factor to make the movie here. I’m glad because you get a beautiful look at a beautiful place that wouldn’t be known without the train,” she added. (This and other stories from the making of the film are also shared in Fred Wildfang’s book Hollywood of the Rockies: The Spirit of the New Rochester Hotel.)

For A Ticket to Tomahawk, released in 1950, she shared writing credits with her husband Richard, who also directed the film. “Screenwriting was really a ‘social avocation’ for her,” remembers Tish Nettleship, who was like a daughter to the screenwriter and is the founder of La Senora Research Institute. She notes Mary Anita was a Stanford University-trained archaeologist. “Researching and writing accurate history was her love.”

But Mary Anita, then 40 years old, put all that aside at just the right time. “Mary Anita wrote a delicious comedy of the times, and her real coup [was] she talked her Navajo friends into being in the film and playing Pawnees,” Nettleship says.

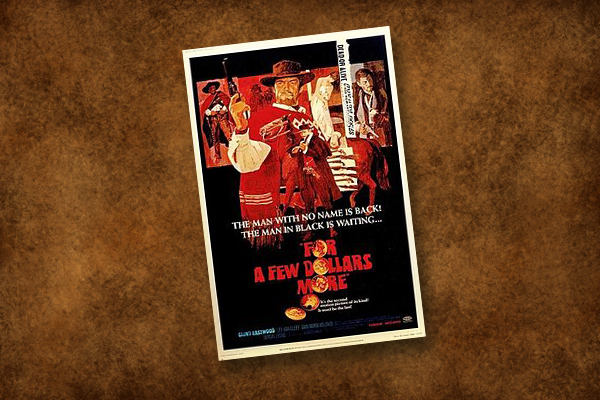

The basic plot of this Western set in 1876 is a race between the train and stagecoach. Anne Baxter plays Kit Dodge Jr., the granddaughter of a railroad man. She must get the train to Tomahawk on time with at least one paying customer to win a Colorado Territory franchise. Her passenger is Johnny Behind-the-Deuces, a traveling medicine show entrepreneur played by Dan Dailey. She’s opposed by a stagecoach line tough called Dakota, who is played by Rory Calhoun. The film had everything: cowpokes, an Indian attack, a narrow gauge steam train and a pretty young blonde who was so unknown she got no screen credit whatsoever, but who everyone will recognize as Marilyn Monroe.

Marilyn plays one of four dance hall girls on the train who perform an impromptu song and dance with Dailey— “Oh, What a Forward Young Man You Are”—on the way to Tomahawk. YouTube runs a clip of that song and dance.

The #20 locomotive used in the film is from the Rio Grande Southern, a narrow gauge railroad built in 1891 by Otto Mears that ran from Ridgway to Durango. Owned by the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden, the 20 is “undergoing a full restoration to operating condition in Strassburg, Pennsylvania,” says Jim Pettengill, vice president of the Ridgway Railroad Museum. It was “gussied up” in garish paint for the movie and named the Emma Sweeny. (A replica of the locomotive was created by 20th Century Fox for close-ups and later was used in the CBS series Petticoat Junction.)

“Mary Anita was presented by the railroad a commemorative plate showing the ‘Emma Sweeny’ as star of Ticket to Tomahawk,” Nettleship says. “Another such plate was presented to the railroad’s engineer for the filming, and his grandson brought his family’s plate as a gift to La Senora when we did our first official screening of the film.”

Mother Nature Steals the Spotlight

The gussied up locomotive did not capture everyone’s attention; nor did a cute Marilyn Monroe in a yellow hootchie-cootchie outfit. What struck filmgoers was the dress that Mother Nature wore as the line traveled up her mountain.

“Mary Anita’s movie had such gorgeous scenery that people started showing up at the closed railroad office asking to take a scenic ride,” Nettleship says.

The movie reviews took notice. In the All Movie Guide by Hal Erickson, he writes, “The film’s never-take-a-breath action scenes are played out against some of the most gorgeous Colorado scenery ever captured on Technicolor.”

The New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther wrote on May 20, 1950: “It was filmed, for the most part, amid scenery that is lovely on the Technicolored screen. Shot very largely on location in western Colorado, it does have an airiness and a beauty that you don’t often find in such films.”

The official website of the railroad today cites Ticket to Tomahawk as its first savior. (Director Raoul Walsh actually captured it first on film, for a train robbery scene in 1949’s Colorado Territory; but Loos made the railroad a star in her screenplay.) Other movies shot on location followed: Across the Wide Missouri, Denver & Rio Grande, Viva Zapata!, Around the World in 80 Days. By the time Hollywood used the railroad line in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, in 1969, the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge was both a National Historic Landmark and a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

Charles E. Bradshaw Jr. bought the line as it approached its 100th birthday in 1982. He restored the original engine #481, and after 20 years in retirement, it went back into service. He continued his restoration work, replacing some 10,000 railroad ties, weatherizing engines and coaches for winter use, and expanding the line. “By 1986 there were four trains running to Silverton with a fifth running to Cascade Canyon Wye!” the railroad’s website states.

“Old Hollywood” Stories

Just as colorful as the tale of the movie is the story of the woman who wrote the script.

Mary Anita Loos was born on May 6, 1910, in San Diego. Her father was Dr. Richard Loos, cofounder of the Ross-Loos Medical Clinic. She grew up in a California hacienda built by Jose Mojica, an operatic tenor and Mexican movie star who became a Franciscan priest. He sold it to her father. She eventually inherited it, but she always kept Mojica’s former bedroom ready for him whenever he visited California.

“So Mary Anita had all the Mojica stories, many of which were highly confidential,” Nettleship says.

Ticket to Tomahawk would bring Mary Anita her biggest fame as a screenwriter. She and Sales were nominated in 1951 for the Best Written American Western by the Writer’s Guild of America.

Besides writing, she was a producer, publicist and actress. Her last recorded writing credit for Hollywood was as one of three writers for the 42nd annual Academy Awards in 1970.

Eventually, financial circumstances led her to sell the hacienda to her friend Lyle Wheeler, and she moved a few blocks away. She continued attending dinner parties and events at the hacienda. When it was sold to La Senora in 1976, “Mary came with it as its docent,” Nettleship says.

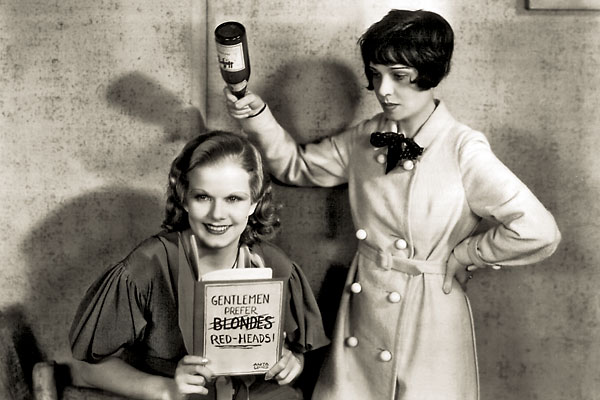

“Throughout her lifetime Mary Anita continued to entertain in the hacienda, bringing the elite of Hollywood talent to the new owner’s dinner table to transfer the ‘Old Hollywood’ stories to a new generation. When she married for a second time in 1980 she did so at the hacienda, with her best friend Eddie Albert singing all the verses of September song to a virtual roster of the still living Old Hollywood talent,” Nettleship says. She notes that Mary Anita’s aunt Anita Loos was the more famous screenwriter of the family; among her novels adapted for film is Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, starring, you guessed it, Marilyn Monroe.

“Over almost 30 years of celebrating all family holidays with Mary Anita, taking my newborn grandchildren on their first outings to Great Grandmother Mary Anita’s house and sharing the dinner table several times a month with her elderly (to my young eyes at the time) friends of such accomplishment, I guess I’m a living repository of their stories,” Nettleship says. “To the extent feasible, I’ve confirmed stories told to me.”

Mary Anita died in Monterey in October of 2004. But her film that so changed history lives on, as does the railroad it saved.

Today, the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad provides year-round service. As it was from Day One, the historic locomotives are 100-percent coal fired and steam operated. The line is operated by American Heritage Railways.

As the locomotive winds up that stunning mountain, with scenery so spectacular you think you’re in a postcard, you can almost hear the steam locomotive singing, “Yes I can, yes I can.”