In 1870, a former Union Army general named William Palmer supervised construction of the Kansas Pacific Railway into Denver, Colorado.

The arrival of the first steam engine as it chuffed into town at 15 miles per hour connected the community of not quite 5,000 people to the rest of the country. A route north to Cheyenne, Wyoming, attached the Union Pacific’s east-west corridor to either coast.

Palmer recommended southbound development, with extensions to coal fields, mills and mining camps, to his Kansas Pacific employers. Favoring east-west migration routes, they turned down his proposal. As a result, the strong-minded, 33-year-old engineer formulated plans to build his own railroad.

An Appetite for Adventure

Palmer’s passion for travel and trains was no accident. After a straight-laced Quaker upbringing and high marks in Philadelphia schools, he took a job with the Hempfield and Pennsylvania Railroads, hiking for miles through wilderness to survey new routes. As he wrote to a friend, “Nothing stops us—for a railroad line must be a straight one—a locomotive is not proficient at turning corners.”

To expand his engineering knowledge, the teenage apprentice traveled to England to learn more about fuel and transportation. While in Europe, he made important business connections, which he captured in copious notes in his journals. To pay expenses, he sold journal articles he wrote. He also saved money by lodging with acquaintances. His knowledge and confidence grew, along with a healthy appetite for adventure.

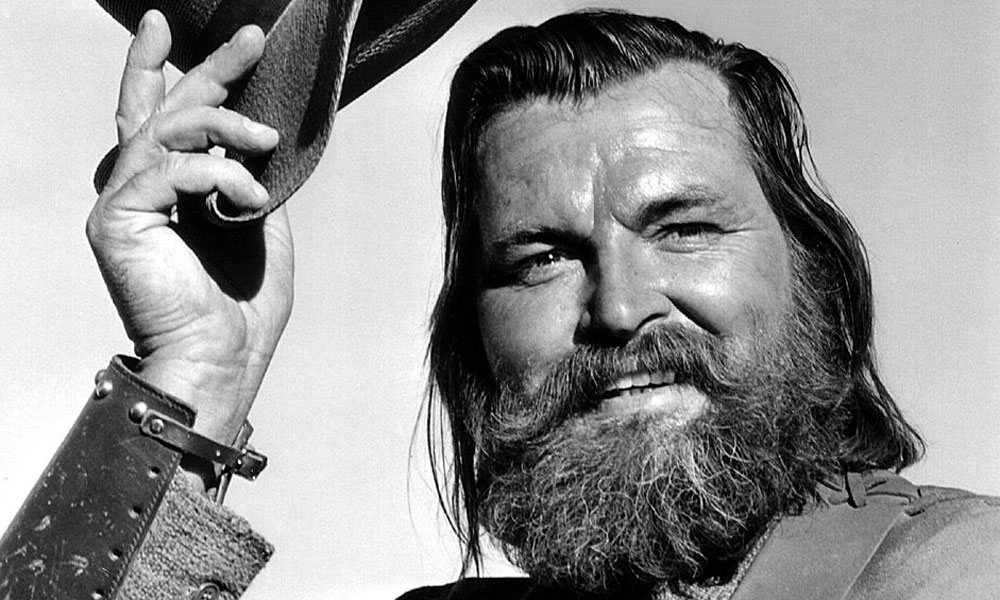

When Palmer returned home to Philadelphia, the threat of Civil War was looming. He faced a pivotal dilemma. Although his Quaker religion opposed war, his opposition to slavery was strong. He felt motivated to take action. A seasoned horseman, he joined the Union Army as a cavalry captain. He assembled an elite crew of trusted friends and acquaintances, which became the 15th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment.

During the war, Palmer was captured as a spy behind enemy lines. He could have been hanged. Instead, he survived several months in a Confederate prison, where he cleverly adopted a false name, and was released in a prisoner exchange. He then located and regrouped his old regiment. When he left the army, he was a general, and he received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

After the war, the Rocky Mountains lured him westward, and he went to work for the Kansas Pacific Railway, an eastern division of the Union Pacific. In 1869, when he first saw Pikes Peak, he wrote in a letter, “Riding as usual on top of the coach, I got wet. But what of that? One can’t behold the Rocky Mountains in a storm every day.” Seduced by the “free air and lonely plains” of the West, he envisioned a new railroad company, in which, a “host of good fellows from my regiment should occupy the various positions.”

Once the Kansas Pacific was completed into Denver and Palmer’s work was finished, he left the company. With little to offer beyond determination, enthusiasm and plans for a new railroad, he traveled back east to call on any and all business contacts, in search of private investors. During the course of his travels, he met and courted 19-year-old Mary Lincoln Mellon, known as Queen, from Flushing, Long Island.

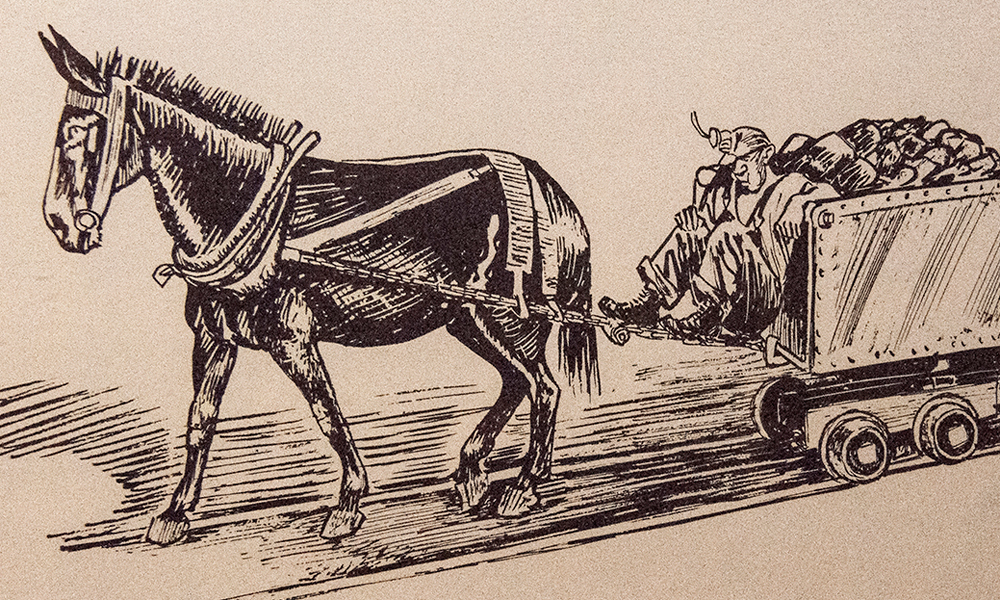

After traveling to see Colorado for herself, where Palmer was hoping to build a home at the foot of Pikes Peak, Queen agreed to marry him in 1870. The newlyweds honeymooned in England, where Palmer met several times with his British business partner Dr. William A. Bell, a pal from an 1867 Kansas Pacific survey trip. Bell provided introductions to investors in London, while the pair studied narrow gauge construction. At three feet wide—instead of the standard four feet, eight-and-a-half-inch width—the rails were lighter weight and cheaper to build. More important, they allowed for steep grades and sharp turns on rail routes “through the Rockies, not around them.” This would become the motto for the fledgling Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, known as the D&RG. The entrepreneurs ordered the 30-pound narrow gauge rails from Wales.

The Dream Begins

Throughout the West, industrialists with visions of progress and wealth raced to build railroad empires and claim land rights for expansion. Palmer’s D&RG joined the competition. Grading and roadbed construction began south from Denver. New towns sprang up along the route. American Indians viewed the intrusion with a combination of curiosity and alarm. Train rides were offered to win their goodwill and calm their fears.

As he promised, Palmer began building a home at the foot of Pikes Peak. In 1871, when the D&RG arrived there from Denver, one log house existed in the barren town site, which would become Colorado Springs. While Palmer built his house, new residents arrived daily and the town grew. He visualized a city which would become a destination for travelers from all over the world.

Palmer pushed railroad construction toward New Mexico, pouring all resources into the narrow gauge line, widely known as the “Baby Railroad.” Clashes were inevitable with competing companies. In 1878, when the D&RG reached westward along the Arkansas River toward the Leadville mining camp, a branch of the Santa Fe line challenged the D&RG’s right to claim the narrow Royal Gorge Canyon.

A two-year skirmish ensued during which tempers flared and neither side budged. Conflict erupted when one company hired employees away from the other, mail service was disrupted, telegraph lines were cut and construction equipment was thrown into the river. The gunslinging lawman Bat Masterson was imported from Dodge City, Kansas, by the Santa Fe Railroad to maintain law and order. Firearms were drawn, but no blood was shed.

In April of 1880, a court ruled in favor of the D&RG, allowing them to continue building through the canyon. Hostilities from the “Bloodless War” lingered. Even though the smoke had cleared, Palmer cautiously built a private schoolhouse for his children to protect them from kidnapping by rival companies.

Caution: Bumps Ahead

While the D&RG expanded, difficulties increased, finances stretched and maintenance deteriorated. To pay for land, repairs and supplies, investor interest payments were held back, as well as paychecks to employees, who were fatigued by long hours and back-breaking work. When a new board of directors accused Palmer of expanding the road too quickly, he resigned as president of the D&RG in 1883. His focus shifted toward development in Mexico and building a D&RG branch route, the Rio Grande Western, with connections to Salt Lake City and Ogden, Utah.

At the D&RG, problems amplified when a new president named Frederick Lovejoy was appointed. He resented Palmer, and he relished moving ahead without him. In a fit of temper, Lovejoy ordered a crew to tear up a mile of track west of Grand Junction, Colorado, near the Utah border, paralyzing interstate train travel between the two states. Soon after, the stalled D&RG and the Western lines both went into receivership until finances could be resolved, and tracks and hostilities mended.

By 1886, passengers in Utah eagerly bought tickets to ride the Western and the D&RG narrow gauge “through the Rockies, not around them.” The meandering 735-mile route took 35 hours to Denver, passing through beautiful mountain scenery. Passenger tourist traffic increased, placing greater demand on the transportation network.

As interstate traffic increased, the Baby Railroad presented a problem. Standard gauge transcontinental trains could not cross Colorado unless the roadbed contained a third rail, to allow for either standard or narrow gauge transit. Although three rail roadbeds were provided, narrow gauge rails were slightly shorter than standard gauge rails. Train cars rode unevenly, which caused dangerous shifts in freight and burning hot box fuel, and uneven wear of equipment and wheels.

Meanwhile, the D&RG appointed another new president, David H. Moffat, who planned a bold, direct route across the Rockies to increase interstate traffic. In 1887, Moffat announced that all D&RG railways would change to standard gauge. The railroad ordered 21,000 tons of steel for new rails at a cost of $6 million. By 1890, the railroad’s conversion to standard gauge was complete.

“The Road is His Monument”

In 1901, Palmer sold his railroad holdings at a huge profit, for $6 million. With expansion into Mexico abandoned after New Mexico routes were claimed by the Santa Fe, Palmer sold his interests there as well. His method of celebrating retirement and financial success was unique. He rode the rails in a lavish private train car, connecting to one train, then another. He traveled the lines, a wandering nomad, looking up old friends, workers and employees—pioneers who built his original railroad. Imagine their surprise and amazement when Palmer arrived and presented them with sizable monetary gifts, amounting collectively to more than $1 million.

Palmer’s final years were highlighted by a 1907 reunion with his loyal friends from the 15th Pennsylvania Cavalry troop. Immobilized by injuries due to a fall from his horse, Palmer paid all expenses to transport the surviving soldiers from his regiment to Colorado Springs for a week of reminiscing, sightseeing, hospitality and a rip-roaring grand party at his recently restored Glen Eyrie mansion.

Palmer died in 1909 of complications from his riding accident. In a 1920 speech to D&RG employees, Dr. William A. Bell said: “The present generation has little conception of the work done by Gen. Palmer. It is apt to think of later men as builders of the Rio Grande. The road is his monument. Those who followed have built on the foundation he laid. His work was in a virgin country in which he believed as few men are given to believe. He thought and acted in a big way.”

Joyce B. Lohse is the author of the 2009 biography General William Palmer: Railroad Pioneer, published by Filter Press.