“Venison used to be sold over the block here, just like beef….

“Mrs. Dan (Diudonne) Lajeunesse ran the Thomas Hotel for a time [1900]; she had venison on the bill of fare. I often sold it to the hotel. I suppose there were game restrictions then, but none paid any attention to them; deer were plentiful,” recalled Alec Berg of Superior, Montana.

A restaurant’s bill of fare, décor, purpose and prices varied greatly from one locale to the other. Location, prosperity and clientele were the major factors that made those determinations.

Consider the Ward House in San Francisco, California, which operated during the Gold Rush in 1849. Those fortunate enough to strike it rich dined out on items like these:

– Oxtail soup, $1 ($29.06 today*)

– Baked trout with anchovy sauce, $1.50

– Curried sausages, $1

– Irish potatoes, 50 cents ($14.53*)

– California eggs, $1

– Jelly or rum omelet, $2 ($58.11*)

– Curlew (game bird), roasted or boiled, $3 ($87.17)

– Mince or apple pie, 50 cents

Compare that bill of fare to Gardiner’s Restaurant in Salt Lake City about 30 years later. You could get ham, bread, butter and vegetables—all for 20 cents ($4.45*). Hot meat, pork, veal or kidney pies were 10 cents ($2.23*). Eggs, pork chops, beefsteak or veal cutlets with bread, butter and vegetables cost you 20 cents. If you wanted to splurge you could spend 35 cents ($7.79*) on stewed Cove oysters. Gardiner’s claimed it served the finest custard cream in the city at 25 cents per pint, 35 cents for a quart or 65 cents for a gallon.

Keep in mind not all restaurants were fancy Victorian places. Edinburgh, Scotland, native Billy Whytock ran a restaurant in San Angelo, Texas, where he settled in 1884. He recalled, “Later, after saving some money, I went into the restaurant business with a partner. This restaurant was called by outsiders the ‘Fighting Restaurant’ and it was rightly named. There was scarcely a night that a fight did not occur.”

Mollie Grove Smith was more impressed with a unique item in an El Paso restaurant rather than its fare in the late 1800s. “Another time I went with my father to El Paso. I saw my first street cars there. We went into a restaurant to sat [sic] and I went with my father into a small room to wash up. I saw a big fat Chinaman standing behind a door pulling a rope. I could not imagine what he was doing and was very frightened. Afterwards I found out that the rope that he was pulling operated some fans over the tables in the restaurant.”

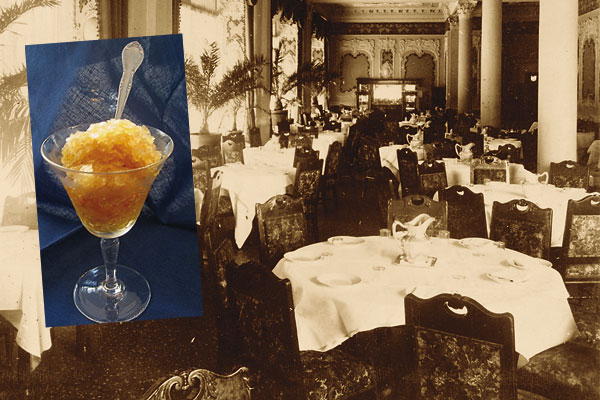

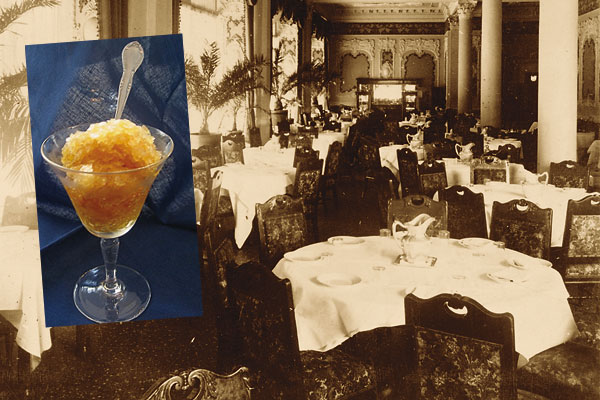

One of the crowning jewels in the West was, and still is, the Brown Palace Hotel in Denver, Colorado. Guests have been spoiled here since its opening on August 12, 1892. The main dining hall, on the eighth floor, was two stories high and offered a beautiful panoramic view of the Rocky Mountains. The hotel kitchens were also on that floor, and just above them were the servants’ dining room, staff dressing rooms and lavatories. The menus were as lavish as the hotel itself and included dishes such as broiled lake trout with anchovy sauce and lamb chops a la Nelson. Like many restaurants at the time, it served a punch similar to our sorbet course today, Roman Punch . Punch was generally served before the roasted meat course. This potent punch not only cleansed one’s palate, but one’s mind as well.

* Computed via Consumer Price Index (measures how much money is needed today to buy consumer good during the year in question).

Roman Punch

2 cups water

1 c. Madeira or Port wine

1/2 cup brandy

Juice of 1 1/2 lemons

2 cups sugar

Mix all the ingredients in a bowl and stir until the sugar dissolves. Pour into a container that will go into the freezer. Freeze overnight. Serves 4.