At this moment, on Clerkenwell Green in London, England, a lean cowboy with steel-blue eyes loosens his Colt’s revolver in its holster and pushes through the batwing saloon doors looking for a shot of redeye and the outlaw who shot his partner. He’s a character in a pulp Western novel, a much-maligned fiction genre which is still alive and well, thank you, in the heart of Great Britain.

One early successful Western was Owen Wister’s The Virginian, published in 1902. It was the first Western to sell more than a million copies. Wister termed it “colonial” because he saw Wyoming Territory as a colony of New England, and “romance” because it is based on “action and episode.” He viewed the American cowboy as “the last romantic figure upon our soil.”

The Western is descended from the historical romance, popularized in 1814 by Sir Walter Scott in Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Kenilworth and other novels in his Waverly series. Before Owen Wister, Fenimore Cooper romanticized New England’s northwest frontier in The Pioneers, The Prairie and The Last of the Mohicans.

Novels in the early 19th century were found in upper class home libraries. They were thick, large and bound in durable cloth or leather, and they were heavy. All of this made the novels expensive to manufacture and expensive to ship. Then the Beadle brothers entered the picture.

The Beadles published the first “dime novels” in 1860. These were skinny and flimsy, printed in small, often blurry type on cheap pulp paper. They looked more like what we’d call a leaflet.

But they were cheap, and they were portable. They offered passengers riding on stagecoaches or on the railroad something to read other than newspapers. Dime novels could fit into a purse or pocket and if left on the seat by mistake, they were no big loss.

Move ahead to 1869 when a flamboyant individual named Edward Zone Carroll Judson began selling romantic stories under the pen name of “Ned Buntline.” His first dime novel featured the exploits of “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Buntline’s novels spawned a whole pack of books known variously as “dime Westerns,” “paperbacks” and “pulp Westerns.” Anyone with 10 cents to spend could thrill to the improbable adventures of Buffalo Bill, Deadwood Dick or Denver Dan the Road Sport. Or if readers preferred a heroine, they enjoyed the exploits of Daisy Dare and Lariat Lil.

Sales of Beadle-style dime thrillers started to decline around 1890, but by then a slightly thicker version had been born. Throughout two World Wars and a Depression, the pocket Western flourished. Publishers like Ace, Bantam, Dell and Pocket Books kept them coming. You could find them in soldier’s packs, sailors’ duffel bags and lunchboxes of working stiffs.

Many of the cheap paperback Westerns were written under pen names. Some were by Frederick Glidden, writing as Luke Short. You could buy Ramrod or Raw Land in 1943 for 25 cents. Or a book by Joseph Ernest Nephtal Dufault, who wrote more than 20 Westerns, including Smoky the Cow Horse, under his pen name Will James. Another author whose books found their way into saddlebags and overall pockets was Frederick Faust, who lived to see Destry Rides Again made into one of them newfangled movin’ pictures. He was Max Brand, of course.

It’s tempting to say that pocket Westerns have gone the way of the butter churn, never to be seen again. The old books themselves are falling to dust as the acidic wood pulp paper succumbs to atmospheric chemistry. Where are the short, fast-moving Westerns you can carry in your coat pocket? Where are the authors with colorful pen names, authors who turn out four or five titles per year?

In England, that island where Sir Walter Scott popularized historical romances with action-driven yarns about horsemen, savage warriors, rebels and outlaws.

Robert Hale Ltd. of Clerkenwell Green in London started the presses in 1936 and, according to the founder’s son John, “has always published Westerns.” In the 1980s the British company began a line known as Black Horse Westerns. “There are about 200 Westerns in print at any one time, and we publish 72 titles per annum at the moment,” John Hale says. “The chief virtue of these stories is that they should make a gripping read.”

You won’t find Black Horse Westerns in many bookstores or revolving racks at truck stops, because they’re manufactured for distribution to public lending libraries in the U.K. “Each title is borrowed an average of 5,000 to 6,000 times in its first year on the shelves,” one researcher reports. Book collectors like them: each 160-page Black Horse Western is printed on library quality paper with ample margins and readable type, bound between collectible “paperboard” hard covers. At least two British online booksellers keep Black Horse Westerns in stock: Amazon.co.uk and WHSmith.co.uk.

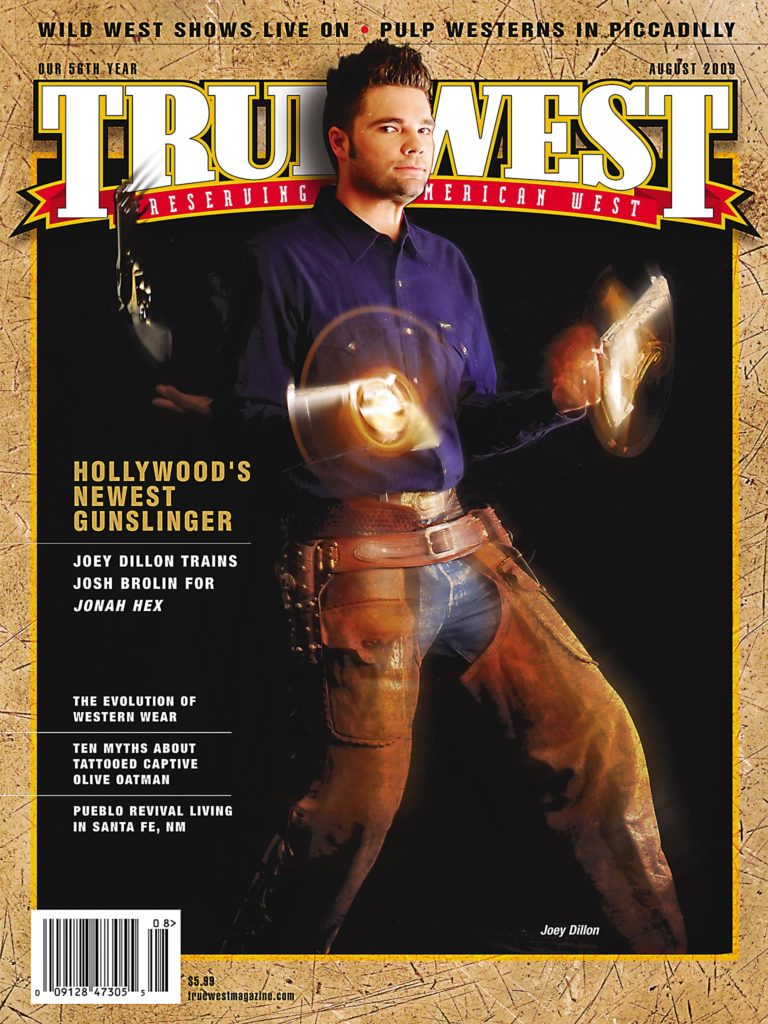

Black Horse authors come from England, Australia, Scotland, Canada and the U.S. Several of them keep up the pulp pen name tradition too. Last year, more than 50 different pseudonyms appeared on 72 new Black Horse titles.

In the Robert Hale Ltd. Internet catalog you’ll find noms de plume like “Owen Irons,” “Jack Sheriff,” “Chap O’Keefe” and “Lance Howard.” Irons and Howard are pen names for American authors, respectively, Paul Lederer and Howard Hopkins. One fifth of the writers of Black Horse Westerns hail from the United States.

“One American,” writes Hale, “sadly now dead, had [more than] 40 live pseudonyms on books he wrote for us, which I have always regarded as a remarkable achievement.” That author was Lauran Paine, whose more than 900 books included The Open Range Men, which was adapted for film as 2003’s Open Range.

Some of the pen names are used by women. “Terry Murphy,” for example, or “Ty Kirwan” and “Gillian F. Taylor.” BlackHorseWesterns.com ran an article about Irene Ord, born in Darlington, UK, who died at 83.

She was a grandmother who wrote dozens of Westerns under pen names such as “Tex Larrigan,” “Curt Longbow,” “James O. Lowes” and “Newton Ketton.”

If you’ve thought about writing a Western yourself, you might wonder what happens to a submitted manuscript. Or “typescript” as it is called at Robert Hale Books. When it reaches the offices on Clerkenwell Green, it is read by John Hale or an editor and is accepted or rejected. If accepted, it is sent on to a copy editor “well versed in Westerns” who has “quite a library of reference books” to draw upon. After the editor has corrected your mistakes and double-checked to be sure you didn’t use smokeless powder in a cap-and-ball Remington, the typescript goes into the Production Department to become a Western novel of about 160 pages, bound in paperboard covers with a colorful action picture on the front.

From there it goes to the public lending libraries on Hale’s subscription list. Some copies are held back for online booksellers. After a year or so, your book will likely be sold to Ulverscroft, who will publish it as a large print edition in its Linford Western Library series.

BlackHorseWesterns.org offers samples from Black Horse Westerns, along with articles about Western writing and biographical sketches of authors. The website is an independent effort created by Black Horse writers and readers.

Ned Buntline would have been overjoyed if his books had attracted a worldwide following of fans so loyal they began a website about him. What makes these writers and readers so loyal to the BHW brand? The short answer is that, amid all the consumers of stories about psychopaths, sex addicts, dysfunctional humans and vampire aliens, there remain readers who just like a “good gripping yarn” about a plausible hero, the American cowboy.

Make no mistake: the cowpuncher is a mythic hero. Owen Wister summed it up in 1902: “his wild kind has been among us always, since the beginning: a young man with temptations, a hero without wings.” As such, whether he comes riding out of Hole-in-the-Wall or Clerkenwell Green, storytellers will keep his legend alive.