When former Sen. Fred Thompson took the floor of Congress in October 2002 and declared Sheb Wooley to be an official “American treasure,” Wooley was definitely surprised.

When former Sen. Fred Thompson took the floor of Congress in October 2002 and declared Sheb Wooley to be an official “American treasure,” Wooley was definitely surprised.

Sheb’s widow, Linda Dotson-Wooley, says, “Sheb got a little teary-eyed. He never realized that he’d done anything much.”

“As far as he was concerned, all his life he was just havin’ fun. Of course, after that, whenever I asked him to take out the garbage, he’d say, ‘Well, I don’t know if American treasures take garbage out,

do they?’”

Wooley died from leukemia less than a year later, on September 16, 2003, but national obituaries and congressional honors notwithstanding, few people really had any idea of how many people Wooley touched in his 82 years, and continues to touch even today.

Only minutes ago, I turned on the TV and found Wooley acting opposite Gene Hackman in the 1986 movie Hoosiers. During a commercial break, Mastercard used a Roger Miller song, “Walkin’ in the Sunshine,” as background music. It was Wooley who set Miller’s career in motion when he taught his much younger cousin-in-law how to play guitar back in Erick, Oklahoma, years before the world had so much as a glimmer of “King of the Road.”

Wooley is often credited as having cut the first commercial record in Nashville at the end of 1945. And it was the former rodeo-er Wooley who taught Clint Eastwood how to ride and, more importantly, tolerate horses. And he taught James Dean how to talk twang in his final movie Giant (1956).

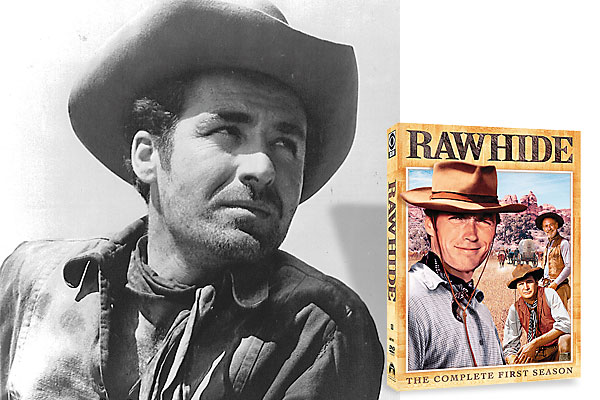

Those most familiar with Wooley know him as scout Pete Nolan on the CBS show Rawhide (1959-65), a series that was created by Charles Marquis Warren, who had previously cast Wooley in several films, including Little Big Horn (1951). Rawhide also starred Eric Fleming and the young gangly Eastwood.

The rest of the world is more likely to remember him for having one of the biggest novelty hits in the history of pop music, “The Purple People Eater,” which was number one on the pop charts for six weeks in 1958, was covered by everybody from Judy Garland to Screaming Lord Sutch and sold, over time, as many as 100 million records.

Beyond the many roles he played in features like High Noon and the variety of TV shows he acted in throughout the 1950s-1960s, beyond the straight-up Country and Cowboy albums he recorded and the many parody and novelty tunes he released, usually as his besotted alter-ego Ben Colder, and besides having written the theme for Hee Haw, Wooley is responsible for one of the most entertaining bits of movie trivia in the world.

It’s called the Wilhelm scream, named by sound designer Ben Burtt after a character in the 1953 movie Charge at Feather River, and there are entire websites devoted to it. Suffice it to say that it can be heard on every print and DVD and videotape of every Star Wars movie, every Indiana Jones movie, two Lord of the Rings films, Superman Returns, the new King Kong and X-Men: The Last Stand. Dozens of movies, TV shows and videogames have employed the Wilhelm scream, a sound bite of horror, pain and shock recorded by Wooley for the 1951 movie Distant Drums, and used as the sound made by a guy being devoured by an alligator. It’s as though Wooley’s scream represents a kind of Tom Joad moment of movie agony, “Wherever there’s a guy being mangled, maimed or mutilated, I’ll be there.” There aren’t any awards given for the best anguished shriek, but if there were, Wooley would have won it every year for over half a century.

Linda Dotson-Wooley keeps her husband’s memories, as well as his business, alive, even while she operates her own, the Dotson-Wooley Entertainment Group, out of Nashville. We spoke over the phone one afternoon while she was knee deep in construction workers and yapping dogs.

HCB: Linda, how did you meet and get to know Sheb Wooley?

LDW: Sheb and I both moved here to Nashville the same year, by coincidence, in ’78. I was trying to build my management and public relations businesses, and get my writin’ goin, and he came to me askin’ me to manage him, and that’s how we went into partnership. And after a long time, well … He always used to say on stage, “Linda said she was tired of getting 10 percent—she wanted it all.” (Laughs.)

Of course, the thing about Sheb is that he straddled music and movies equally.

And how cool, too, because I’m telling you, there was so much going on and so many people that I was privy to know, and still know, the ones who haven’t passed on, and the families of all the cowboy actors—Autry and John Wayne and Ben Johnson, who was one of my favorite people in the world.

Where did he get all that talent? He’s like Will Rogers, coming out of Oklahoma and accomplishing so much in so many areas.

That is a good comparison because he was a great fan of Will Rogers. He once said Oklahoma was so desolate that the only entertainment was to cut a hole in your pocket and play with yourself. (Laughs.)

Sheb had to be creative. He would lay awake at night when he was nine, 10, and he couldn’t sleep because his mind was going so fast about how he wanted a big herd of cattle and a big ranch and horses, and he’d imagine what each one looked like. Same time, he’d hear people on the radio and think, I can sing these songs, and he had this gift of writing words and singing melodies. He was just born with music in him.

When he was about 12, he put together this little band, the Plainview Melody Boys, and he promptly walked into the radio station and told this man, “I want to do a show, a morning show every weekend,” and the man said, “Well, okay.” Sheb was fearless.

So he set out to be a singer and songwriter in the mid to late 1940s, in Nashville?

He first came to Nashville writin’ songs for Ernest Tubb, Hank Snow, Eddy Arnold. Eddy got Sheb to mow his grass. (Laughs.) And then when Sheb got tired of that, and he didn’t think Eddy was going to record any of his songs, he stopped mowing his lawn. (More laughs.)

He just got up and said, “Think I’ll be an actor now?”

Ernest Tubb and some others did end up recording some of his songs—but somebody told him, you’re a very nice lookin’ man and what you need to do is go to Hollywood and get in them movies. So Sheb just packed up and went there.

Being a good rider must have helped.

He was a great horseman. He would do these movies where he would have a small acting role, but he would also wrangle and show the other actors how to ride.

Within about six months, he got his first role with Errol Flynn in Rocky Mountain [1950]. He and Errol looked like twins, both of them with beards.

I read once that a woman mistook him for Flynn.

And he played it to the hilt! (Laughs.) Figured if the girl thought he was Errol Flynn, he’d just belly up to the bar!

Seems like Charles Marquis Warren played a big part in Sheb’s career, beginning with Little Big Horn through Rawhide.

I think he was helpful in making suggestions and in passing the word on getting Sheb work. Sheb admired him and everything but remember, he left Rawhide for a year? It was contract time and Sheb thought, I’m gonna get me a raise. (Laughs.) And they cut him—he got fired for a year. They brought him back, but he did butt heads with Charles Marquis Warren a bit. He said, “Well, I thought I was invincible, and I found out I wasn’t.” (Laughs.)

And Sheb is one of the three bad men stalking Gary Cooper in 1952’s High Noon.

Well, High Noon. I’d hear him be asked many times in interviews what was his favorite movie to be in, and it was High Noon. He loved Gary Cooper; they became very good friends. He obviously had the same kind of personality of a good old cowboy as Sheb did, and Ben Johnson and all of them who we knew.

It’s funny, even though Sheb’s scenes were cut out of Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo [1959], he was in both pictures. Hawks often said he made Rio Bravo as an answer to High Noon. He said, in High Noon, a guy asks for help, and he can’t get it; and in Rio Bravo, people are offering help, and he won’t take it.

That’s interesting—I had not heard that before. Maybe that’s why he ended up cutting him out. (Laughs.) I think there might be one tiny little piece left of Sheb in there somewhere, because he still gets residuals on it. (Laughs.)

You know, I’ll tell you a part he was cast for, and turned down, was Lonesome Dove.

Is that right?

Yeah, and the character he was cast for was that guy who was a little bit squirrely. I forgot his name, kind of a silly-type fella, and Sheb didn’t like it, so he passed. Sheb didn’t do what he didn’t want to do.

I’m guessing Sheb and Clint Eastwood got along pretty well.

Oh yeah. Clint called every once in a while. He still does. Sheb taught him how to ride a horse, though he was allergic to them. I have a picture of them on Sheb’s ranch at Ojai in California, him and Sheb diggin’ an outhouse in the mountains—a one-holer. (Laughs.)

They camped out a lot on the ranch, and they’d go horseback ridin’ in the mountains. It’s a preserve now. Taken by the government—you know how they do.

Seems to me that Eastwood could have just dropped off the map after Rawhide.

You’re right. He could’ve easily. Clint is sort of like a little phenomenon or something. ’Cause he didn’t even really like actin’ that much anyway. And he was always sneezing at the horses and the hay around him. He hated ridin’ but then he got into it after Sheb had taught him to ride. But he said, “I get so tired of pushin’ these cows around.”

Sheb always said on his music shows, “Well, I was the scout on Rawhide, and it was my job to go into town first and round up the girls for Clint Eastwood.”

Was it Clint or Sheb who said that he was tired of pushin’ the cows?

It was both of ’em. They said, we’re just sick of pushin’ ’em around in little circles.

What’s the story with Eric Fleming? Eastwood never talks about him.

Well, you know, Eric was a hard one to … they liked him, all the people on Rawhide liked him, all the cast members, but he had a very, very dark past, and I guess he just didn’t trust anybody and so he didn’t know how to love. He wouldn’t join in any if they got together to have a little party or something. He was hard to be around or even be a friend to, although I guess if anybody could say they was a good friend, it was Clint and Sheb.

And then he went to Peru and got eaten by piranhas. Sheb said that Eric had had a premonition about dyin’ young and also a premonition about the scene he was getting ready to do in the river down there, and it took them a couple of days to do it ’cause he felt like, I don’t want to do this. And then he went out there and fell out of the boat and was eaten.

You know, they don’t talk about piranha in most of the bios.

I know they don’t.

They say that he drowned, but not that he got eaten—

He drowned because he had holes in him. You drown quick if you get eaten into a million pieces.

It’s nice that Sheb kept acting, even while his tour schedule was so busy.

He had pretty much retired to Nashville when I met him, from movies, and I told him he was too talented for that, so he went and did The Dollmaker (1984), with Jane Fonda, and The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) and Silverado (1985).

Some of those guys we talked about did their best work late—Ben Johnson, for example.

Absolutely. And Ben Johnson was one of the nicest, most wonderful cowboys in the world. He and his wife, just beautiful. Anybody who met him—he was so much like Sheb—normal good old cowboys. And that feeling is not there with a lot of people these days. There’s not a lot of good old cowboys out there who were raised with respect, raised poor and hungry, but who respect women and horses.

Not necessarily in that order.

Not necessarily in that order, you’re exactly right. (Laughs.)

When did you first find out about the Wilhelm Scream?

Isn’t that the wildest thing? Ben Burtt, who worked for Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, and works now for Pixar, he brought that to my attention. Think they all got into a contest that every movie they would make they would use that scream. It was so awesome! And Ben Burtt sent me a collection of clips from Star Wars and Indiana Jones and everything, and it’s so awesome to hear Sheb keep screamin’ and screamin’ and screamin’! (Laughs.)

I guess they established finally that it was Sheb who recorded the scream.

I didn’t even know they were looking to confirm it until they got in touch with me, and I had all the information when he was doin’ the movie in the swamps and stuff, and that they had him come in and loop after. And he said they had him come in and scream and scream and scream and scream and scream and scream, and he just thought it was funny that he had to do it.

That scream first came out of Distant Drums, didn’t it?

Distant Drums, that’s right. They were making the movie in the swamps and stuff. And then he said, when they did that, he said he hated doing that movie because of the snakes and everything.

Did Sheb ever talk about Johnny Guitar [1954] or Giant [1956]?

I do remember he once said that on Trooper Hook (1957), Barbara Stanwyck had a heavier beard than he did. (Laughs.) Don’t recall he ever mentioned Johnny Guitar.

I’ll tell you a funny story. When Sheb was called for Giant, he actually thought, because he read the whole script, he thought he was reading for Jett Rink, James Dean’s part, but what they did—they let him know afterwards—they had to teach James Dean the manner and tone of how Sheb spoke; they wanted James Dean to speak like that. So Sheb read all his lines for him and worked with him for about three weeks before the movie for him to be, he was sort of like a dialogue coach. They did cast him in a smaller part, but he liked being there because he liked James; he was kind of like a little brother to him. In fact, James had asked him to go ridin’, he was so proud of that new Porsche, he asked Sheb to take a ride with him, and Sheb had something else to do, and he didn’t. And the next day I think is when he died.

Sheb and Johnny Cash were very close, weren’t they? They toured together in the 1950s.

You know, I’ve got six hours we taped with Sheb telling stories that nobody’s ever heard, great stuff, stories about people that are so funny. Bob Wills and different actors and Johnny Cash road stories. Stories about how when they were touring together, Sheb and Johnny used to destroy hotel rooms, ’cause they both drank a lot. One hotel, they moved all the furniture out of their room out to where the elevator opened in the hallway. They set it so when the elevator opened, it looked like you were looking in somebody’s room. And they called the boy who was working the nightshift. They said, “we got a problem with our room,” and the boy came up, and at three in the morning, and there’s Johnny laying in the bed, and they said “we’re mad, we need this taken care of.” So he went back down, called his boss, had his boss get out of bed. And in the meantime, Sheb and John moved everything back into the room.

Another time, they painted the room black—everything, the TV, the furniture, the commode. And one time, they cut the legs off of all the furniture.

Johnny and June lived right around the corner from us on the lake [Old Hickory Lake, near Hendersonville, Tennessee].

We’d all visit each other on jet skis or whatever. It’s the one that was just bought by Barry Gibb; he’s rebuilding it now.

That’s something they didn’t show in Walk the Line, Sheb and Mrs. Wooley meeting up with Johnny and June on jet skis.

Let me tell you what, there’s a lot of stuff they didn’t show that happened between Sheb and Johnny.

Sheb and Johnny were mentioned in the press because they died so close together [Cash on Sept. 12; Wooley on the 16th].

Actually, Sheb was feeling pretty good the day that we went to visit with the family at a private thing at the funeral home for Johnny. But as soon as we walked through the door and he saw Johnny, it just, his knees buckled under him, and he got sick right then, and I had Marty Stuart and some others help me get him to the car. And within hours, he was dead after that.

It took it out of him, did it?

It did. I think it was that when he saw Johnny he thought, okay. You know? I’m just guessing but it seemed to me, it was like, “Here’s my buddy, and he’s younger than me, and I been hangin’ on and I’m okay to go now.” He wasn’t sad—he was happy when he died, but to see Johnny there, it really hurt him a lot.

You know, he wanted me to get him a pine box. And I said, “Sheb, are you sure?” He said, “I’m a cowboy, and I don’t like wastin’ money.” He said, “Find somebody to make me a pine box,” and this was years before he even got sick. And then, when he did get really ill, I was looking on the Internet and found this monastery in the Midwest, and they grow their own trees and make their own linens. And I called them and spoke to one of the fathers, and so they handmade him a pine casket, like in the Old West, screw on the top, and they stuffed his linens with straw. And it was the most beautiful thing ever. He got what he wanted.

Was it cheap?

Oh, no. It wasn’t cheap, but it was beautiful. And he saw it before he died. Here’s what he wanted me to do, so I wouldn’t have to pay storage on it. He said, why don’t you have them ship it from the monastery, and I’ll put my socks and underwear in it. (Laughs.) That’s who he was—so sensible on the one hand, but so wild and wooly on the other.