The night of October 18, 1915, was relatively normal for the passengers on board the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico Railroad train—until around 10:45 p.m.

The night of October 18, 1915, was relatively normal for the passengers on board the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico Railroad train—until around 10:45 p.m.

It was about seven miles north of Brownsville, Texas, headed into town, when the engine suddenly derailed. The engineer died; the fireman was severely hurt. But that was just the start of things.

A group of 60 men had caused the wreck by pulling one of the rails. They swarmed the passenger cars, shooting Anglos on sight. Three were killed, and three others wounded. The raiders made off with about $325 in cash in addition to jewels, watches and even shoes. They then headed across the Rio Grande. The whole incident took less than 15 minutes.

The history books note that the holdup was the work of Tejanos and Mexican renegades, using the chaos of the Mexican Revolution for their own purposes—to get money, to kill whites or maybe even to wrest control of the Southwest from America.

But it was more than just an extreme case of outlawry. The wreck and robbery was part of a Mexican invasion of Texas. It’s a story that’s been untold—until today.

Plan de San Diego

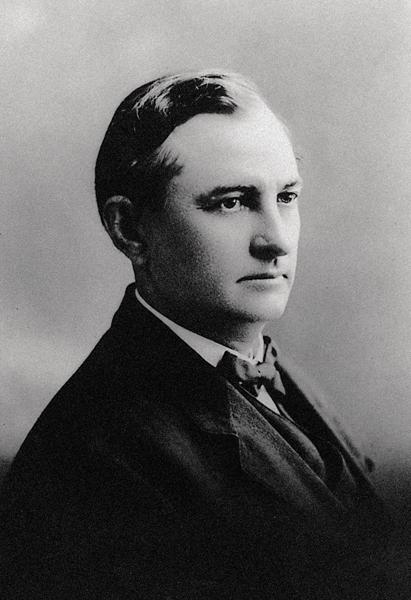

Enter Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler, emeritus history professors at New Mexico State who have spent more than 20 years looking into what’s known as the Bandit War. Their findings are published in The Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution: The Bloodiest Decade 1910-1920.

They’ll tell you that the Mexican Revolution isn’t well understood in this country. In reality, it was a series of uprisings by various factions, each trying to grab control in Mexico. The best known group was led by Pancho Villa. But other figures also jumped into the fray, notably Venustiano Carranza, a regional governor. Carranza didn’t look like a revolutionary—his long, white beard gave him the appearance of a Santa Claus. He was anything but a jolly old elf; Carranza was brilliant, devious and ruthless to a fault. He used people to achieve his ends. By the middle of 1914, he was the de facto ruler of Mexico.

And he was the man behind the Plan de San Diego.

The Plan was a manifesto, supposedly written and signed in the small Texas village of San Diego—although Harris and Sadler doubt that claim. It’s also unclear who wrote the thing. But the message was striking.

The Plan called for a popular uprising of American blacks, Hispanics and Indians in February 1915. They would capture Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and California—which would all revert to Mexican control. But even more alarming to American residents living near the border, the Plan ordered all Anglo males over the age of 16 to be killed.

So why did Carranza put together such a far out document? It’s unlikely that he really believed that Mexico could regain control of Texas and the Southwest. But the Plan could get him diplomatic recognition from the US government. The key, of course, was to keep Carranza’s role hidden from the Americans—and to blame his rivals or his Tejano allies for the violence that was to come. He played on the arrogance of U.S. and Texas officials, who believed that no Mexican was smart enough to pull off such a deal. Instead, they took the Plan at face value.

Bandit War Begins

In spite of the February start date, the onslaught didn’t really begin until July 1915. A band of 30 Mexican raiders roamed across south Texas, robbing and threatening residents, and killing at least one Anglo. Only about 12 Texas Rangers were assigned to the entire region, so they couldn’t control the situation. Local law enforcement was also understaffed.

Texas Gov. James Ferguson asked for federal troops to get involved, but officials in the administration of Woodrow Wilson turned down the request. They believed that the banditry was nothing more than local feuding, something for state and local authorities to deal with (although U.S. Army troops already stationed in Texas could return fire if attacked). Further, the feds refused to provide money for additional Ranger positions.

So Gov. Ferguson, under pressure from residents and commercial interests in south Texas, found some extra money to create Ranger Company D. And he ordered its first captain, Henry Lee Ransom, to clean things up using all means necessary. Ransom had a “shoot first and ask questions later” reputation, and he was more than happy to comply.

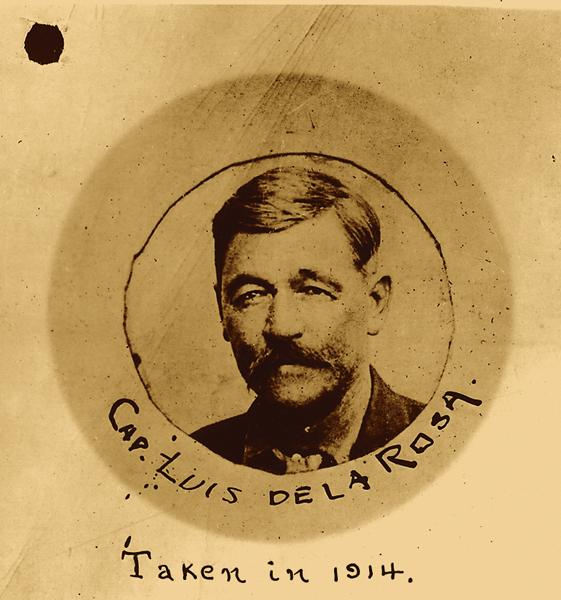

On August 3, 1915, a full-out battle between U.S. forces and a group of raiders took place at Aniceto Pizaña’s ranch, some 18 miles north of Brownsville. (Pizaña—along with former Cameron County Deputy Sheriff Luis de la Rosa—would become known as one of the combat leaders of the Plan.) One cavalry private was killed in the clash and three other Americans were wounded before the Mexicans and Tejanos escaped.

Fourteen Plan warriors attacked the town of Sebastian on August 6. They robbed a store before capturing and murdering two members of the local vigilante group. Rangers and local law officers responded by hitting the ranch of a suspected Plan member and killing him and one of his sons.

Things picked up just two days later. A detachment from the Army’s 12th Cavalry, along with some customs inspectors and the local deputy sheriff, went to Norias, home to the sub-headquarters of the legendary King Ranch—the giant cattle operation run by the Kleberg family. Norias was 70 miles from the border, but there’d been reports that a Plan raid was in the works. Sure enough, about 60 riders attacked in the evening of August 8. The 16 defenders held out for more than two hours, even though four of them were wounded. The Americans were running low on ammunition when the bandit leader was shot and killed. His followers decided to retreat—leaving seven Mexican corpses behind. This was the biggest battle of the Plan, and it led to some of the most striking photos of the period.

Texas Ranger Capt. Monroe Fox and two men lassoed the bodies and pulled them into a pile—a moment captured on film that created the impression that the Rangers had participated in the fight. The Rangers also advised the soldiers on what they’d have done had they been there. One of the defenders, customs inspector Joseph “Pinkie” Taylor, finally had enough: “ We were here when they came, we were here when they left, and we are still here, and I don’t know what you would have done if you had been here, but I do know THERE WAS NOT A GODDAM SON OF A BITCH OF YOU HERE!”

Instead of aiding in the search for the Plan members who had escaped, the Rangers helped interrogate a wounded raider who had been captured during the battle. He reported that the bandits had expected no resistance at the Norias ranch—and were surprised when bullets started to fly. The captive died just after giving his statement. It’s likely that he was tortured and, perhaps, executed.

Other photos of the dead were also taken—including the striking shot of Ranger Jack Webb holding a skull in one hand and a pistol pointed at it in the other. Tejanos saw the pictures and were sickened. Many considered the photos a terrorist tactic by the Rangers.

Misplaced Warfare

Tensions were running high. The Anglos were in fear of a local uprising, while Tejanos feared brutality from the Rangers.

Governor Ferguson responded by increasing the size of the Ranger force and ordering almost all of it to south Texas—with particular emphasis on the King Ranch properties, where manager Caesar Kleberg used them like a private security force.

General Frederick Funston, the commander of the Army’s Southern Department, now began to see that the situation was bad. He knew that at least some of the raiders came from south of the border, so the belief that the whole thing was just Texas politics-turned-violent was out the window. But he and federal officials still didn’t connect the dots to understand that Carranza was behind the attacks.

Funston positioned 40 small Army detachments throughout south Texas—a total of 2,500 men—figuring that more raids were imminent. And a number of skirmishes with bandits did take place through August. But beyond that, Rangers and vigilantes took some tough measures, ordering Mexican Revolution refugees who had come to Texas for sanctuary to go back—or else die. At least some Tejanos and Mexicans who were thought to be tied to the Plan were simply killed, no trial necessary.

But the brutality wasn’t one-sided. The Mexicans attempted a number of assassinations of U.S. officials; a couple of which were successful. On September 24, nearly 100 Plan fighters—accompanied by Carranza soldiers—crossed the Rio Grande and attacked the town of Progreso. They looted and burned the place, and captured Army Pvt. Richard Johnson, taking him with them when they retreated back to Mexico. Johnson was executed, and two Carranza men removed his ears as souvenirs. His head was cut off and placed on a pole for the Americans to see.

Still, U.S. authorities failed to blame Carranza for the attacks. His military leader, Gen. Emiliano Nafarrate, kept saying the raids were committed by a few renegades—a blatant lie that could have been checked out. For example, Plan leaders Pizaña and de la Rosa escaped to Mexico and stayed under the protection of Carranza—he even paid their bar bills.

In the meantime, the bloodshed continued into October. After the train holdup on the 15th, Gen. Funston had had his fill. He asked the War Department to approve a “no quarter” order—the troops would take no prisoners. The request was turned down, but it shows the level of anger and frustration. By this time, the Army had 5,000 men in the region, with more coming.

The federal Bureau of Investigation—the predecessor of the F.B.I.—was also involved. It wanted to hire hit men to assassinate some Plan leaders. Surprisingly, Washington okayed it—but a local U.S. attorney protested, and the plot was shelved. Still, Gov. Ferguson offered a dead or alive reward for Plan chieftains. No one took advantage of the money.

But the Plan de San Diego was just about finished anyway. On October 19, the United States gave diplomatic recognition to Carranza as president of Mexico. Five days later, he ended the Bandit War—and abandoned his Tejano allies, some of whom were captured or killed.

Plan Lingers to This Day

Carranza briefly revived the Plan in 1916—it was a ploy to get Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing to stop chasing Pancho Villa in Mexico and return to Texas. And Carranza considered using it in 1919, when he was in danger of losing power.

Carranza’s plot was almost revealed when his military pal Nafarrate threatened to tell the Americans the truth in 1918 (he was angered that one of his men wasn’t given a high government job). The president found a way to protect his secret. Nafarrate was in Tampico, Mexico, to give documents to U.S. officials, but he took some time off to visit a whorehouse the night before. Someone killed him in flagrante delicto.

But the Plan didn’t help Carranza in the long run. In 1920, his regime was overthrown and he was shot to death.

It’s not clear just how many people died during the four months of the Bandit War. Some estimates go as high as 5,000. Authors Sadler and Harris put the American toll at 17 dead and 25 wounded; about 300 Tejanos and Mexicans were also killed.

But the effects linger even today. There’s still a lot of mistrust by residents on both sides of the Rio Grande. And tensions inside south Texas still run deep. The Anglos view the Tejanos as a potentially disloyal group that is capable of violent uprisings. The Tejanos tend to view the Anglos with suspicion, fearing that racial bigotry is always present. And the image of the Texas Rangers is just as split—either the Rangers are seen as a heroic force with an honorable and courageous tradition (Anglos), or they are a brutal, repressive, out of control group that is out to get minorities (Tejanos).

Such is the power of the Plan de San Diego—the only sustained invasion of the U.S. in the 20th century.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy University of New Mexico Press & The Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution / Above: Center for American History at University of Texas in Austin –

– Courtesy Henry E. Huntington Library

– Courtesy Texas Ranger Hall of Fame –

– Center for American History at University of

– Center for American History at University of Texas in Austin –

– Left: Center for American History at University of Texas in Austin –