In 1879, Col. George Washington Miller with son, Joe, then age 11, rode across the Cherokee Outlet, looking for rangeland where they could run cattle.

Miller, originally from Kentucky, had already established an operation in Kansas and northeastern Indian Territory.

The Outlet—60 miles wide and 180 miles long—stretched across Indian Territory along the border with Kansas and was a place where cattle ranchers could lease lands from the Cherokees, but they could not buy them. That year, Miller leased his first lands in the Outlet. This was the beginning of the 101 Ranch.

Since 1871, Miller had operated in partnership with Lee Kokernut, using the LK brand for their cattle; but by 1881, he was on his own and needed a new brand. He chose the simple “101,” which, his sons Joe and Zack say, came about as a result of some roughhousing in San Antonio, Texas, where G.W. and Joe were gathering a herd to push north.

At the time, San Antonio was a bustling cowtown where cattlemen stayed or ate a lavish meal at the Menger Hotel, and where cowboys caroused at a number of saloons, including one establishment at 101 East Second Street that the proprietor, showing absolutely no creativity, called “The Hundred and One.” Here, G.W. and Joe, accompanied by their trail boss Gid Guthrie and some of their cowboys, gathered for a final farewell dinner before trailing the herd north. And here, according to family lore, some of the cowboys drank a bit more than they should have, became rowdy, threw some punches and were ordered to leave. As they did so, one cowboy took the “101” sign from the establishment, affixed it to the chuckwagon and finally nailed it over the cook shack after he returned to the ranch.

Colonel Miller paid for the damages at the saloon, turned the herd north on the Chisholm Trail and reportedly said, “We’ll brand 101 this time. Before I’m done, I aim to make this tough crew so sick of the sight of them figures they’ll ride a ten-mile circle around town to keep from reading that honky-tonk signboard.” Ranch lore claims none of the cowboys ever again frequented the San Antonio establishment that had given the cattle a brand and the ranch a name.

Colonel Miller and the Poncas

Early in his days of running cattle on leased lands in the Cherokee Outlet, Col. Miller formed a mutually beneficial friendship with White Eagle, a prominent Ponca Chief. The Indians had the opportunity to move onto the Cherokee Outlet, obtaining better lands and thereby better living conditions for themselves, and Miller hoped he could then lease some of those Ponca lands for his own ranching operation. But the lands the Poncas eventually controlled in the Outlet were not those Miller sought to lease, so he instead cut a deal with the Cherokees for 60,000 acres in two large pastures: one on Deer Creek, a tributary of the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River that became known as the Deer Creek Ranch, and the Salt Fork Ranch itself. Both ranches became a part of the extended 101 Ranch, so-called for Miller’s trail brand and headquartered southeast of Ponca City, Oklahoma.

Although he did not lease lands from the Poncas, Miller maintained his relationship with them, selling them beef; later, his son Joe would put some to work on various ventures at the 101.

Joe, Zack and George Miller

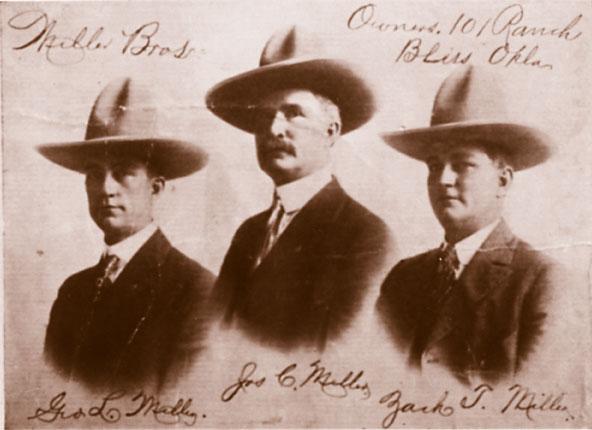

While it was G.W. Miller and wife Molly who settled the 101 Ranch, their sons made it a nationally known operation. Wilkes Booth and John Fish, the first and third sons of G.W. and Molly Miller, died as young boys. But Joe, their second son, became an able assistant to his father, and younger sons, Zack and George Lee, learned to carry on the ranch traditions as well. The Millers also had one daughter, Alma.

The boys were taught the way of the cow by their father before he died in 1903, leaving an operation with an annual income of more than half a million dollars and a crew of more than 250 cowboys who were needed to manage the tens of thousands of head of cattle spread across a range that encompassed 172 mile-square sections of land, or more than 110,000 acres. After G.W.’s death from pneumonia, Molly eventually built an impressive home—known as the White House—where she lived on the land that had nurtured their dream.

Young Joe was only 12 when his father handed him a roll of money and sent him to Texas to “bring back a carload of cattle.” This son was also a showman. He rode rank horses on the ranch and in the rodeo arena; he later formed a Wild West show featuring some of the Poncas his father had befriended. To further diversify the ranch operation, Joe began raising corn and hogs, relying on the science of agriculture to improve production. Zack, a strong cowman like his father, handled the trading and marketing efforts for ranch production, while youngest son George Lee eventually became the financial manager.

The expansive 101 Ranch had schools, churches, its own network of roads, a telephone system and even a horseback delivery mail system. The Miller operation included oil and gas wells, ownership of trains, grape arbors, a cannery, tannery and packing plants, poultry farms, novelty shops, woodworking shops and a general store that accepted federal currency or “101 Ranch” folding scrip and coins made of brass and copper. As Zack Miller noted in an interview for American Magazine in 1928, “We figured it wasn’t much harder to do things in a big way than it was to worry along in a small way. We figured it was no worse to fail big than to fail little; but ever so much better to win big.”

The 101 Ranch Show

One of the successes was the 101 Ranch Show, promoted as “The Real Thing.” And it was. Geronimo, Hoot Gibson, Tom Mix, Bill Pickett and Lucille Mulhall were among the personalities who had a role in the show, an extravaganza that grew from the natural competition among cowboys working the range.

In September 1883, young Joe Miller, joined by Ponca Chief White Eagle, led a delegation of Poncas to the Alabama State Fair where he helped the Poncas establish an Indian village to hold traditional dances. Years passed before the show became a force in Western entertainment, but on June 11, 1905, the 101 Ranch hosted a Cowboy Reunion for the National Editorial Association convention. The show featured a buffalo chase and specialty acts, including the roping and riding of 19-year-old Lucille Mulhall, a world-champion roper from Mulhall, Oklahoma, who had dazzled crowds—including Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William McKinley—in Oklahoma, St. Louis and Washington, D.C.

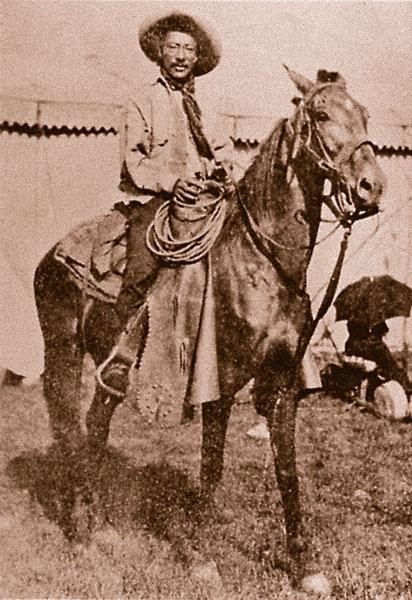

Also riding for that show was Bill Pickett, a black cowboy known for developing the sport of bulldogging, which he accomplished by biting the upper lip of the animal to subdue it rather than using his hands and strength to power it to the ground. Joining him were Apache Chief Geronimo and Oklahoma cowboy Tom Mix, who would become famous as one of the earliest film cowboys.

Ranch Diversification and the Demise of the 101

Cattle, corn and hogs formed the backbone of the 101 Ranch, but the enterprise expanded to the Wild West show; later, the ranch bankrolled energy development, including wildcat oil and gas wells, and motion picture projects. There were tough times along the way as well, including murder charges filed against Zack (he was acquitted), cattle theft charges against G.W. (who died before the case went to trial) and other difficulties (including conflicts between the brothers over land ownership) all leading up to the 1920s, which, by any account, were a rough period for the ranch ending with Joe’s suicide in 1927 and George’s death in a car accident two years later.

The crash of Wall Street’s Stock Market in October 1929 dealt a further blow to the ranch finances, leaving Zack hanging on just barely. By 1932, he had to face the inevitable and in March, an auction call rumbled across the once mighty 101 Ranch as

the cattle, buffalo, horses and hogs were sold. Four years

later, the White House, that impressive home built for Mother Molly (who died in 1918), was taken from Zack. The operation of the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch had run its course, although Zack himself lived until January 3, 1952.

Even though he had lost the ranch, Zack presided over a group his father had organized in 1920, called the Cherokee Strip Cow?Punchers Association. This group of cattle industry folk in the Cherokee Strip disbanded six years after Zack’s death. But the spirit of the 101 Ranch did not die then. In 1968, the 101 Ranch Old Timers Association formed as a revival of this first group, aiming to preserve the memory of this important ranch. Its current president, Jean Evans, is the daughter of Jack Webb, who had been a sharpshooter and trick roper at the ranch in the 1920s. His most dangerous trick was called the William Tell Act—he shot objects off his own head by pulling a string attached to the trigger of his rifle. It’s easy to see where Jean gets her love of preservation from—her parents, who bought part of the 101 Ranch when it was sold off. Jean’s father died in 1956 and is buried on Cowboy Hill, next to his old boss, Zack.

Photo Gallery

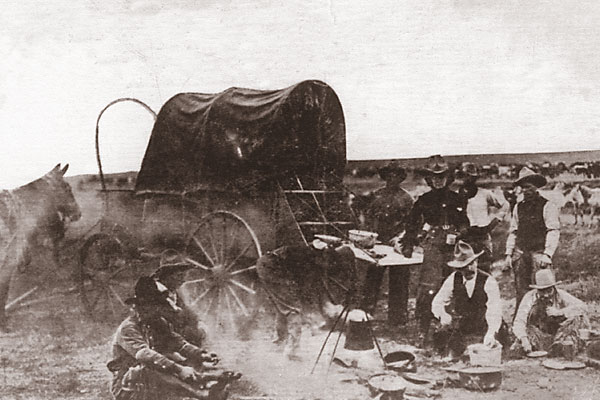

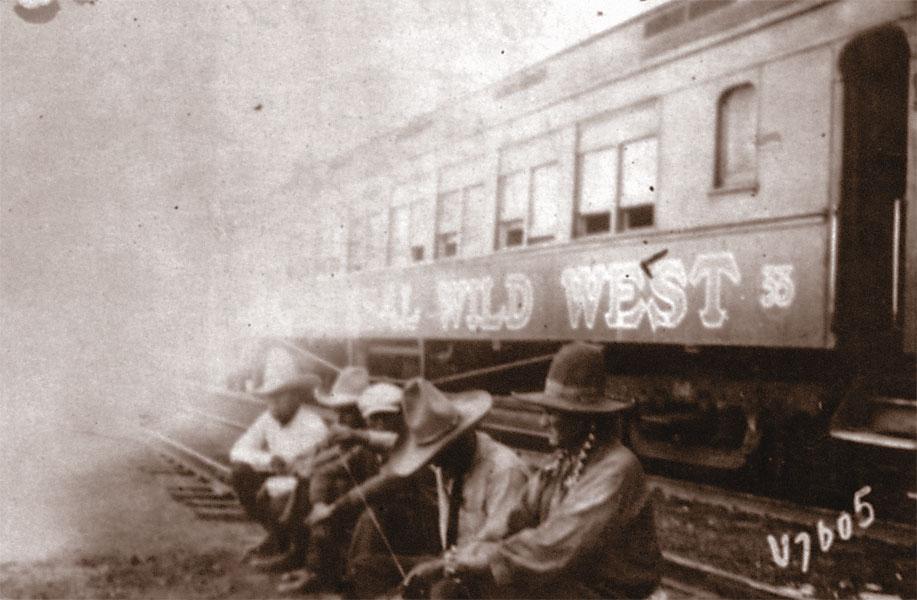

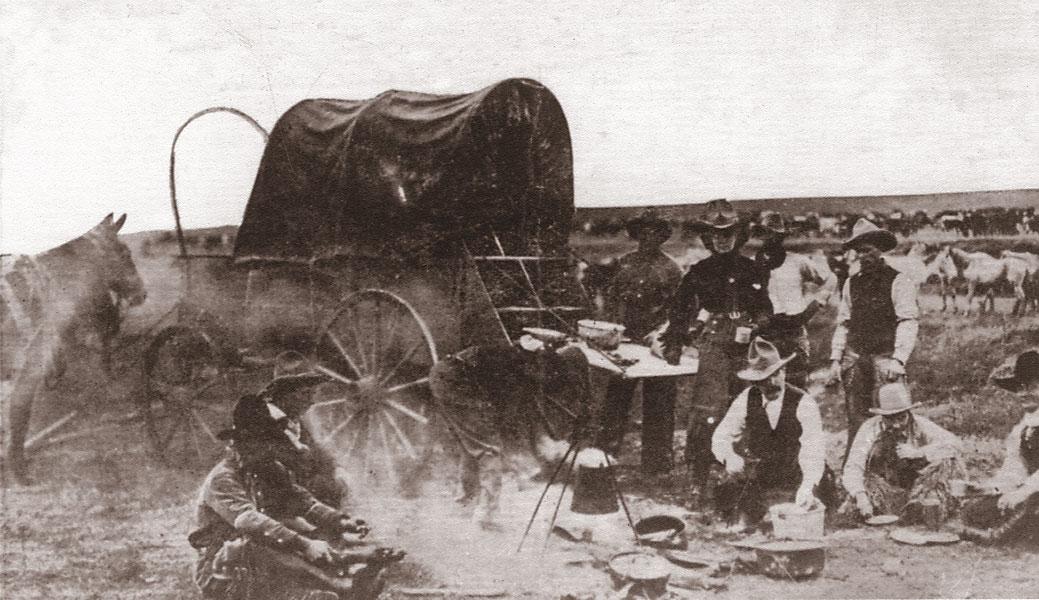

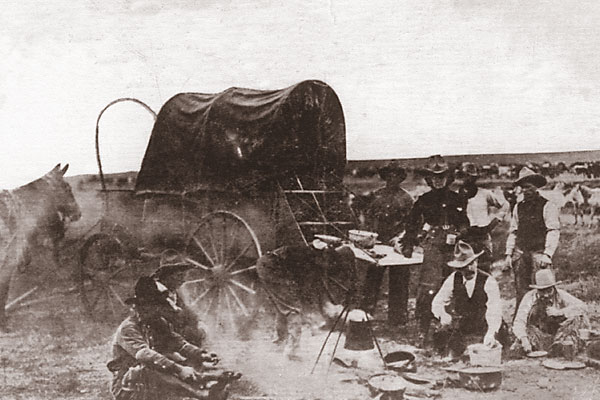

Miller’s legacy is more than just a working ranch and the Wild West show; Easterners also came to dude on the ranch up until 1932. Here are some of the scenes they likely saw: cowhands chowing down dinner on the roundup (above); Wild West show cowboys resting after a long trip (next photo).