They were the leaders of the Indians, whether they conducted war with their traditional enemies, resisted the European invasion, practiced spiritual beliefs or searched constantly for food and shelter and survival. Some achieved their status through heritage. Others, because of repeated acts of bravery or strength of character. And there were those who were strongest in their spiritual powers.

They were the leaders of the Indians, whether they conducted war with their traditional enemies, resisted the European invasion, practiced spiritual beliefs or searched constantly for food and shelter and survival. Some achieved their status through heritage. Others, because of repeated acts of bravery or strength of character. And there were those who were strongest in their spiritual powers.

The chiefs remembered today are generally those who were either bitter fighters against the white man or those who recognized that resistance was useless and destructive, and used their influence to end the conflicts. They won many battles, but it was inevitable that they would lose the wars and their land.

All of the scores of tribes across the West had their chiefs, but none had just one leader. Most tribes were split into numerous factions or bands, each with their own leaders. And different chiefs within one tribe or sub-tribe were recognized by their people for various strengths and responsibilities. There was no “United Tribes of America” with a single leader and spokesman. Failure of settlers to understand Indian leadership division contributed to the failure of many treaties.

Depicted in their traditional clothing and with their handmade accessories and weapons, Indians are among the most interesting and attractive subjects of all photographs. The images of the most prominent chiefs are no exception. Here follows just a few of the great ones. The names familiar today are the English versions of their native names. Unfortunately, some of the greatest chiefs, such as Cochise (Apache) and Crazy Horse (Sioux), left no photographs of themselves.

Photo Gallery

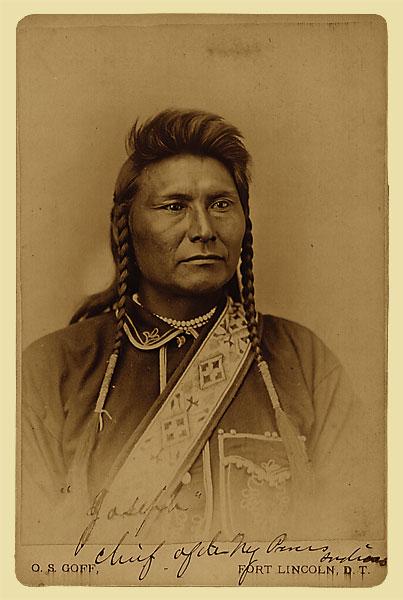

The Nez Perce resided in the Northwest, where today’s Washington, Oregon and Idaho converge. Their most famous leader is Joseph, an hereditary chief who came into power in the 1870s. Not a warrior, he nonetheless was also not inclined toward peace with the whites if it meant giving up his land. He led his people through the 1877 Nez Perce “War” as they resisted being forcibly put on a reservation and instead made their way to Canada. He was later their spokesman and negotiator, and gained widespread respect. He also drew respect by his presence, being over six feet tall and, as this photograph reveals, quite a handsome man.

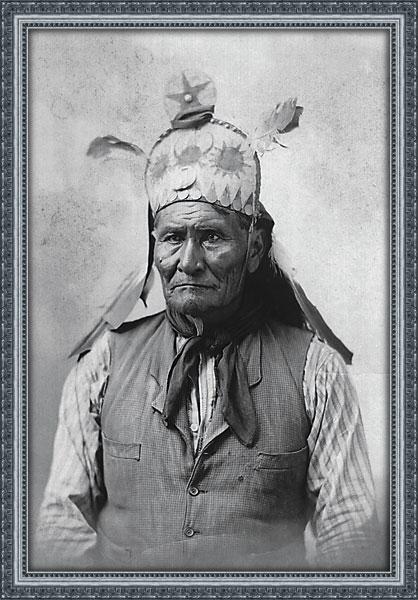

Geronimo’s resistance to the intrusion of the white man began in the 1850s and lasted until 1886. He practiced what we would call guerrilla warfare on both sides of the American/Mexican border. In 1884, he tried reservation life in Arizona but soon bolted to Mexico with his followers. By this time, technology had advanced such that news spread rapidly across the country, allowing Geronimo to achieve a fearsome reputation. Some of the most famous of all Indian photographs were taken by Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly at a council between Geronimo and Gen. Crook in March 1886. Above is one of those photos, showing Geronimo with a few of his warriors before he surrendered (one of a very few photos taken of Indians while hostile). He is pictured wild and free, but he would not be so for long.

Soon thereafter, he was imprisoned in Florida and later moved to Fort Sill, Indian Territory. Pictured here shows a tamed Geronimo, dressed for a photograph for his autobiography, published in 1906. He died a sad death at Fort Sill in 1909.

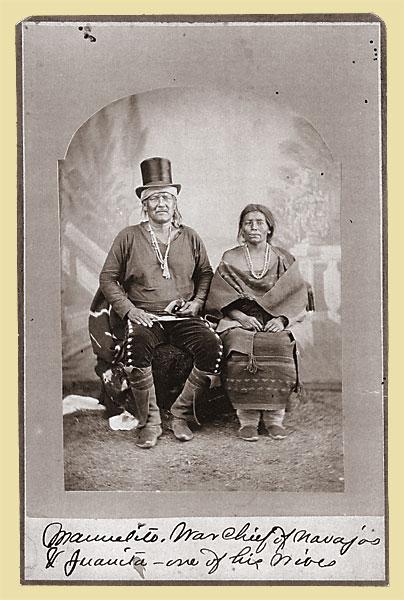

The imposing leader of the Navajo Nation, one of the largest Indian tribes, was the six-foot-six-inch, barrel-chested Manuelito. Residing in the large area of what is now southeastern Utah and northeastern Arizona, the Navajos had been carrying on warfare with the Mexicans for decades and refused to accept the restrictions to their activities established by the newly-arrived Americans. Hostilities continued for several years, led by Manuelito, until the removal of many Navajos to the Bosque Redondo reservation on the Pecos River in 1863. Manuelito refused to go, but in 1866, he surrendered and was sent there. After the failure of the Bosque Redondo affair, Manuelito returned to his native land with his people and remained their chief until 1884. This photograph of him with his “favorite wife” was one of at least two taken by photographer Ben Wittick during the 1882 Territorial Fair in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

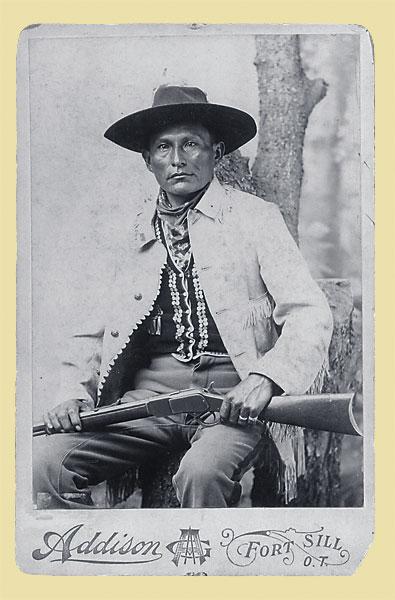

Naiche was the son of one of the greatest Apache chiefs, Cochise, and the grandson of another, Mangas Coloradas. Naiche and his Chiricahua followers frequently joined Geronimo on his raids and surrendered with him in 1886. Thirty years younger than Geronimo, Naiche enlisted as a scout at Fort Sill, Oklahoma Territory, in 1897, when this striking photograph was likely taken. He worked successfully to move the Apaches at Fort Sill to the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico, which was much more like their native homeland. Naiche died at Mescalero in 1921.

Later in life.

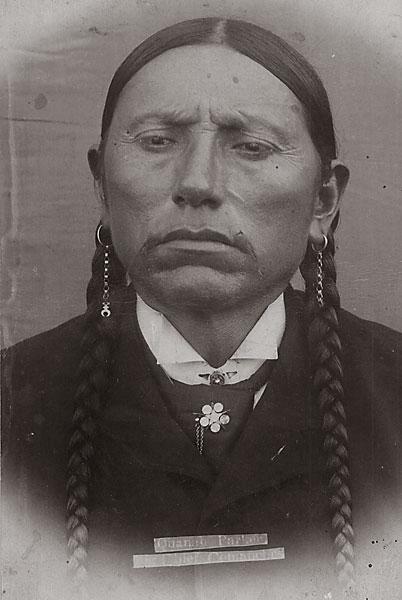

Comanche Chief Quanah was the son of white captive Cynthia Ann Parker, who raised him to respect his Indian heritage. In his late 20s, he fought to resist the intrusion of the buffalo hunters into Comanche territory, leading his warriors at the famous Battle of Adobe Walls. He continued his leadership after his people were located on a reservation in Indian Territory. Dying in 1911, he left behind many descendants—all proud of their heritage.

Red Cloud was both a great warrior and an intelligent negotiator for his people. From the Indian-white struggles of the 1850s to the battles along the Bozeman Trail in the 1860s, he fought to preserve the Sioux territory, taking a great toll on the American troops. Eventually, he became an “unwilling traveler on the white man’s road,” but he remained a strong leader of his people. His face was one photographers loved. This photo, probably taken in the late 1890s, reflects the strength of his character and the sadness of his fate. He died on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in 1909.

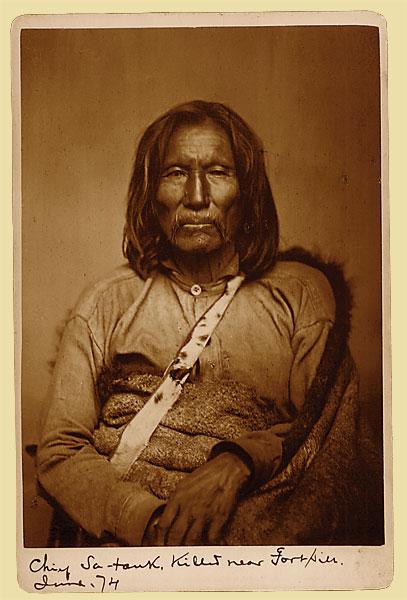

Born around 1800, Setangya grew up in the traditional Kiowa way, before the white man invaded the plains in large numbers. During his 60s, Satank, as he was most commonly known, led many raids on the early Texas settlers. After the Kiowa reservation was established at Fort Sill, he and his followers would locate there but periodically slip away to raid. Following the killing of seven teamsters during an 1871 raid on a wagon train in Texas, Satank was arrested at Fort Sill. While being escorted to trial in Texas, he was killed in a daring and defiant attempt to escape. He was foremost a warrior, said to be cruel and ruthless in his warfare. This photograph, taken when he was in his 60s, seems to justify that description. Because of his mustache and chin whiskers, he was thought to have Spanish blood.

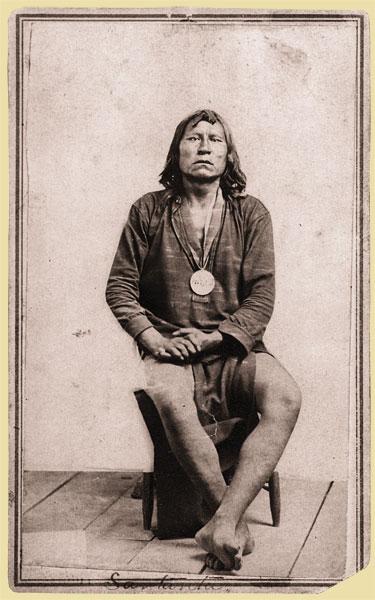

Perhaps the foremost Kiowa chief, Satanta achieved his leadership role because of his skill as a warrior. The New York Times wrote of him in 1867, “in cunning or native diplomacy Satanta has no equal in boldness, daring and merciless cruelty,” adding, there are “good points in this dusky chieftain which command admiration.” Satanta was arrested in 1871 at Fort Sill with Satank and taken for trial in Jacksboro, Texas. Although he was convicted of murder and first sentenced to be hanged, the governor of Texas approved his parole. Satanta was then accused of resuming his raiding and surrendered himself to authorities in 1874. Four years after his arrest, he committed suicide by leaping headfirst from the second floor of the penitentiary hospital. This photograph is dated “August 18, 1868” on the back. He probably received the peace medal he has around his neck at the signing of the Medicine Lodge Treaty in 1867.

Sitting Bull is today one of the most remembered medicine men and chiefs—most likely because he was a leader (although not a combatant) in the battle that defeated Custer, he performed with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show for a short period of time and he had a name people recalled. After the 1876 Custer battle, Sitting Bull took his people to Canada, returning to Dakota Territory in 1881, remaining peaceable but largely unwilling to negotiate and cooperate. He was tragically killed, along with his 17-year-old son, in an encounter with Indian police at his Standing Rock Agency cabin in 1890. A family man (he is reputed to have had as many as nine wives), Sitting Bull looked more like a round-faced, somewhat jolly grandpa than a mighty warrior. Here he is pictured with his grandchild, along with his mother and daughter.