For 50 years, almost nobody remembered Evelyn Cameron or what she’d done in the territorial days of early Montana.

For 50 years, almost nobody remembered Evelyn Cameron or what she’d done in the territorial days of early Montana.

Her name wasn’t in history books or halls of fame, and her contribution to Western history was stashed, literally, in the basement of a friend.

Then writer Donna M. Lucey came snooping around in 1978, looking for photos to illustrate a book on female pioneers. The curator of the Montana Historical Society in Helena mentioned there was a stash of glass plate negatives, but all efforts to display them had been rebuffed by the farm woman who’d inherited Cameron’s estate.

Thankfully, Lucey was a skilled persuader. She convinced Janet Williams to share the treasures hidden in her basement. “I was astonished by what I saw,” Lucey writes in her book Photographing Montana, 1894-1928. “For years I had been traveling throughout the West, combing photo collections for Time-Life Books’ series on the Old West, and I had never found anything like these pictures. They presented an intimate view of pioneer life in eastern Montana, a close-up portrait of men and women who had settled one of the most remote and desolate regions of the West.

“As remarkable as the pictures them-selves was the fact that the photographer, whose name was Evelyn Cameron, was almost entirely unknown except by a few historians in Montana, none of whom had seen more than a small sampling of her work…. Cameron’s name appeared in no general histories of the West nor of western photography. But the few images I had in hand were proof that Evelyn Cameron was a master photographer of the West.”

Originally published in 1990 by Alfred A. Knopf and republished in 2001 by Mountain Press Publishing of Montana, Lucey’s book shares a full history of this remarkable woman who left the luxury of English society on her honeymoon to tough it out in a remote piece of the Old West. The book features about 150 photos from the 1,800 negatives Lucey found in that basement.

From Tea and Fox Hunts

Evelyn Batterseas was born on August 26, 1868, the youngest child of an English merchant who traded in East Indian items and provided a full Victorian lifestyle for his family. There was a plush house, generous grounds and 15 servants. Women were expected to spend their time at teas and fox hunts—women riding sidesaddle, of course—and were discouraged from “unladylike” activities such as education and work.

Little of this suited Evelyn, who in 1889 dismayed her family by marrying a Scot named Ewen Cameron. He shared her love of horseflesh and hankered to explore new lands. Apparently, Evelyn didn’t look back as she enthusiastically boarded a boat for America. “Indeed, the prospect of a life in a remote wilderness suited her perfectly,” Lucey writes. “Not only could she lead the outdoor life

of riding and hunting she adored, she could also escape the scrutiny of her disapproving relations.”

The couple arrived in eastern Montana with an English cook and one of Custer’s scouts as guide, and settled around Miles City and Terry in a stark landscape with “intense solitude.” The cook was soon gone as the couple struggled to make a life. They hoped to raise polo ponies for the European market, but after many years of trying, they finally gave it up. They originally lived off Evelyn’s trust fund, but it wasn’t enough. To help support her husband (and her brother, who now lived with them), Evelyn planted an acre-large garden and sold vegetables, bringing in the only cash the family saw. The garden also, of course, fed the family.

Her second money-making plan (while her husband failed at his attempts to raise cattle) was to take in wealthy boarders, hoping they’d invest in the ranch, but none ever did. The couple wouldn’t find any financial security until Evelyn discovered photography in 1894, basically teaching herself on a dry-plate glass negative Kodak. Although the popular camera company had already progressed to a far easier Kodak model (“you press the button and we do the rest”), Evelyn preferred the old-fashioned method that used five-by-seven plates.

She charged $2 for a family portrait and traveled the countryside drumming up business. By 1902, she had a decent business going, with a photographic “calling card” and regular customers. By September of that year, she’d made $94.40 selling photographs.

She also illustrated the numerous articles Ewen wrote for ornithological journals—often with no photo credit

for herself—but she loved these collaborations and called them “our greatest pleasure in life.”

As Lucey recounts: “Evelyn was fascinated by what she referred to as the ‘New World type,’ the colorful frontier characters who were drawn to the remote areas, and by the how-to of life in the West—how to ‘thrash’ a field of wheat; how to shear a sheep; how to drive a herd of cattle across the Yellowstone River. She did on-the-scene documentary photography of them all.”

Evelyn loved photographing home-steaders posing in front of their meager, but proud shacks and documenting the important moments of their lives: weddings, reunions, Fourth of July celebrations. She often had them dress in their “Sunday clothes.” Besides families, she focused on cowboys and “wolfers”—solitary hunters who lived off the bounty for coyote and wolf skins—as well as her fellow female pioneers.

“In her photos,” Lucey writes, “women are seen riding, roping cattle, tending animals and gardens, cooking for sheep-shearers and farm crews and working in the wheat fields—and her diaries make clear that women were not shielded from the rigors and dangers of ranching and farming.”

Evelyn also wrote and illustrated magazine articles about Montana ranch women, obviously impressed with how hard Russo-German women worked the fields. She recognized the effort because it mirrored her own.

Her 35 handwritten journals, kept painstakingly for some 40 years, as well as hundreds of letters, give an amazing insight into life in those days. “The overwhelming impression one is left with throughout Evelyn Cameron’s diaries is the sheer physical and emotional strength that life in frontier Montana demanded,” Lucey notes. “Work was never-ending and backbreaking and there were few distractions.”

The diaries also have constant references to the ever-present rattlesnakes that are the demons in virtually every Western journal. One day, she actually teased a snake to

“go on the fight” before she “shot its body

to smithereens.” Another time, she photographed a coiled snake at close range.

Most of all, Evelyn spelled out the transformation of Montana Territory. Lucey notes that Evelyn’s photography documented the cultivation of the prairies by the “honyockers”—a derogatory term for homesteaders—while she shared the angst of cowboys and ranchers in watching the land cultivated and fenced up. As Evelyn wrote a friend in 1911: “The range country that you knew so well is about gone now and the prairie swarms with farmers who plough up the land with steam and gasoline engines.”

The Camerons themselves lived on “Eve Ranch”—actually three different sites in the same area and bearing the same name in her honor. They had three rooms: a kitchen, brother Alec’s bedroom and the couple’s bedroom and sitting room. The front porch was the major gathering spot.

What little rest Evelyn got was on that porch, overlooking the Yellowstone River and catching the breeze. Although she didn’t complain, her diary made clear that the bulk of work fell on her shoulders—not only earning the money that kept the family going, but also doing all the gardening, cooking and washing. When the couple went off on their frequent hunting trips, making camp as they sought out wild game to flesh out their diets, Evelyn also was in charge of camp upkeep and helped with the butchering.

Ewen died in 1915, and Evelyn stayed on alone at her ranch, writing a friend that she was so active, she was “as busy as a one-armed man with hives.” In 1918, she became a citizen and voted in that November’s election. She was 60 when she died in 1928 after an appendectomy. Apparently, she knew the end was coming because she killed her favorite horse before leaving for the hospital. The church overflowed for her funeral, but then she was forgotten for a long time.

That oversight of history has been corrected: Evelyn Cameron is enshrined in the National Cowgirl Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas, and in the Montana Historical Society in Helena, Montana. In Terry, the Prairie County Museum houses an Evelyn Cameron Gallery.

Through Evelyn’s photographs and her words, we have a special insight into Montana Territory.

Photo Gallery

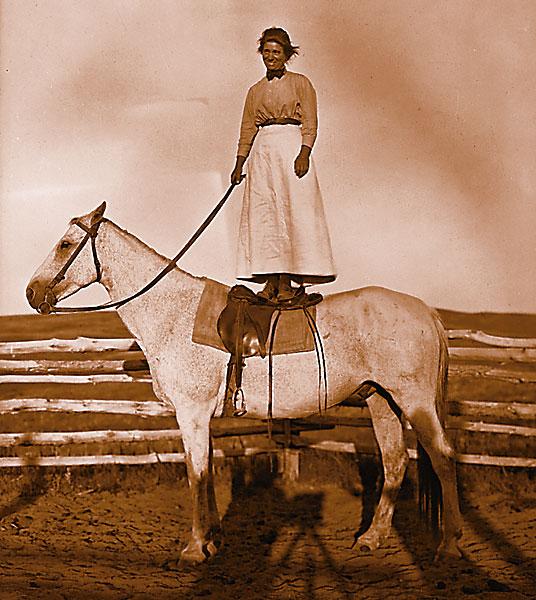

Evelyn Cameron took this photograph of Mary Whaley (wearing a white apron and a cowboy hat) who was one of many women who homesteaded their own claims in eastern Montana. The woman with her hand on Mary’s shoulder is another homesteader, Cap Barker.

– Courtesy Montana Historical Society in Helena; PAC 90-87.224 –

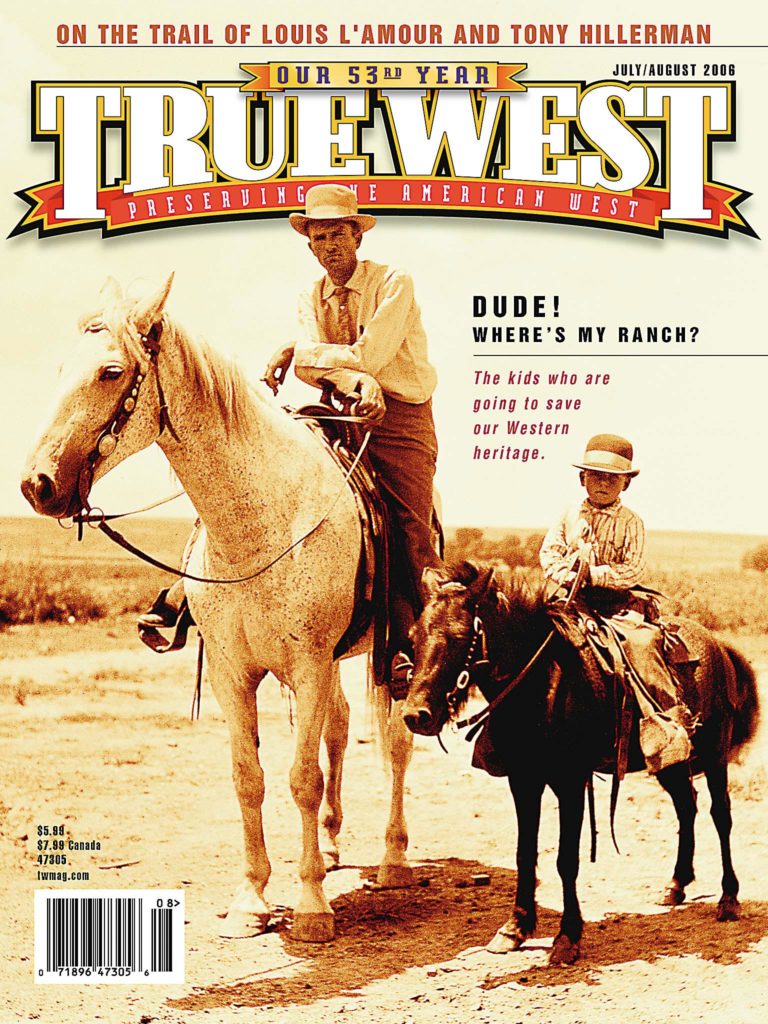

– Courtesy Montana Historical Society in Helena; PAC 90-87.273 –