Disgusted, Wild Bill Hickok tossed down his cards on that fateful August 2, 1876.

Disgusted, Wild Bill Hickok tossed down his cards on that fateful August 2, 1876.

Hickok had joined the table at Nuttall and Mann’s No. 10 Saloon in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, at about noon. Never wanting his back to a bar or door, the legendary gunman first asked young gambler Charlie Henry Rich, seated with his back to the west wall, to change chairs. Only Rich had declined, and Hickok, a gambler himself, did not press the issue. After all, changing seats could change one’s luck.

Card games may require skill, but luck is always a factor. A day earlier, Hickok had wound up busting a miner called Bill Sutherland at the gambling tables. On this afternoon, Hickok’s luck had turned south.

“That old duffer,” Hickok announced after losing to former riverboat pilot William Massie, “he broke me on that hand.”

At that moment, Sutherland—who had entered the saloon earlier—drew and cocked his pistol, firing a round into the back of Hickok’s head. James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok fell off his stool without a word, dead at age 39.

Sutherland would go down in history, and to the gallows, as Jack McCall, and Hickok’s losing hand would also earn a place in history. Later, published accounts stated Hickok had held black aces and black eights (the fifth card was alternately identified as a red jack, queen or nine), now known as the “Dead Man’s Hand.”

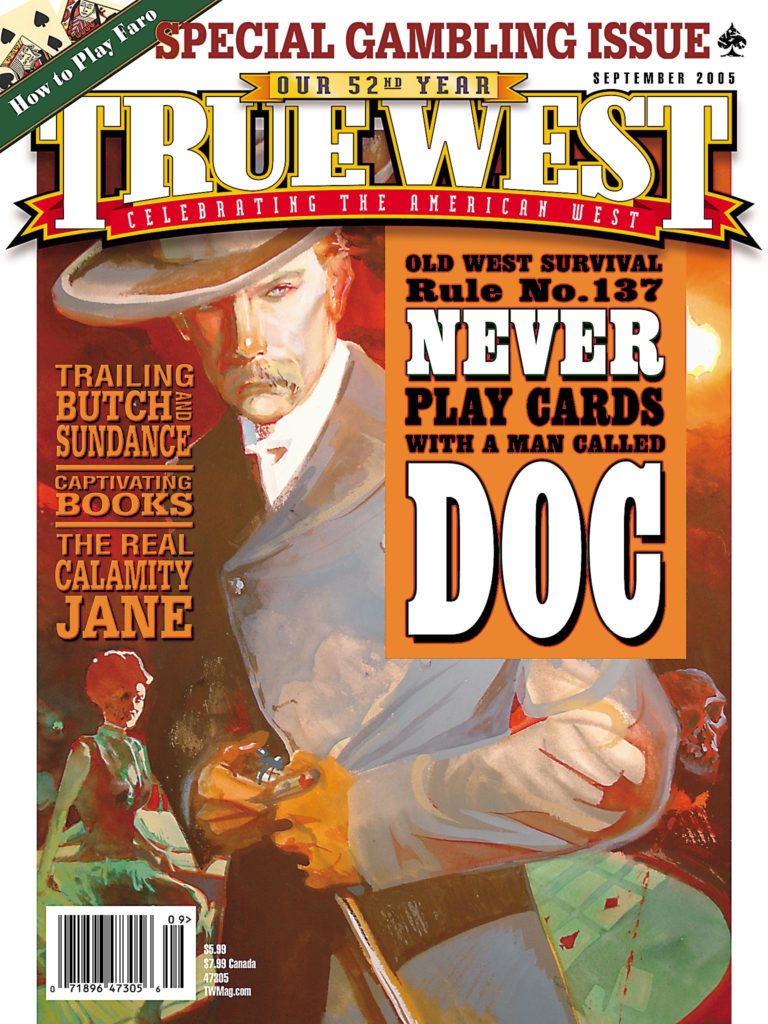

The card game, of course, was poker, booming across America, although nobody could predict the popularity surge a century later. Keno, three-card monte, vingt-un (an early blackjack) and especially faro (favored by Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp) may have had their admirers in gambling parlors across the frontier, but poker (Hickok’s true love) has endured as an Old West icon—even if its roots were planted back east.

Poker’s Tells

Actually, tracing poker’s origins is pretty much a crapshoot. A few believe poker to be an offshoot of an English card game called brag. The Chinese, others hold, invented the game around 900 AD. Maybe it came from ganjifa, played in India. Or perhaps it was born in France. Many trace it to 17th-century Persia, where As-Nas was played with 20 cards. Some theories suggest As-Nas originated even earlier, and that Columbus’ sailors brought the card game to America. Europeans eventually adapted As-Nas: the German version was known as pochen and the French as poque. In any event, by the early 1800s, a version of Old Poker could be found in the gambling dens of New Orleans. From there, poker quickly spread.

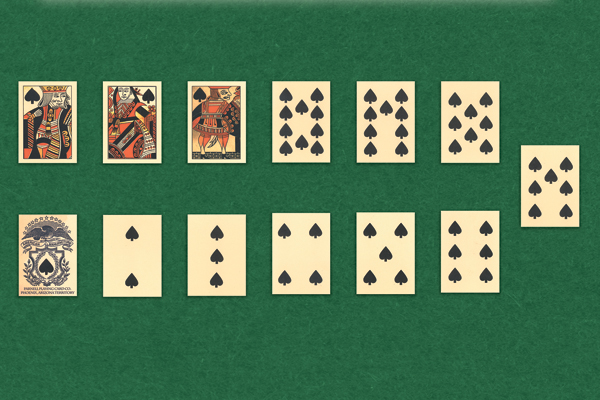

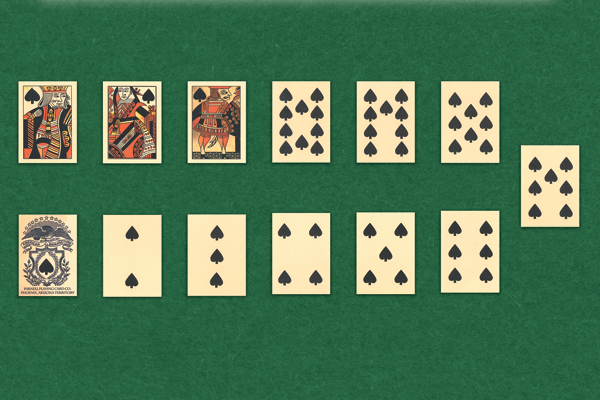

Like As-Nas, the first poker decks contained only 20 cards (in poker: four aces, kings, queens, jacks and tens). Five cards were dealt to each player, then bet and shown without a draw. The 52-card deck first appeared in the United States in the 1830s, but it wasn’t readily accepted until two decades later.

The game, which moved from New Orleans on riverboats along the Mississippi, was known as “the bluffing game” or, simply, “bluff.” Even as late as 1875, Hoyle’s Games cited the game as “‘Bluff,’ or ‘Poker.’” After all, bluffing was—and remains—a key part of the game.

“When there is no limit to the game, it frequently happens that a player with great nerve and a long purse, will bet so high on indifferent cards, that the confidence of his adversaries is shaken, and they abandon their hands,” The American Hoyle noted. “This is called ‘bluffing.’”

The American Hoyle first mentioned “twenty-card poker” and “Poker or Bluff” in its 1845 edition, but there were earlier published accounts. Jonathan H. Greene called it the “cheating game” in Exposure of the Arts and Miseries of Gambling, written in 1834 but not published until 1843 and retitled Gamblers Exposed. Englishman Joe Cowell described a crooked game he witnessed in 1829 aboard the steamboat Helen M’Gregor in his 1844 book Thirty Years Passed Among the Players in England and America.

“He was one of many who followed card playing for a living but not properly coming under the denomination of gentleman-sportsman, who alone depends on his superior skill,” Cowell wrote of a cardsharp. “But in that pursuit, as in all others, even among the players, some black-sheep and black-legs will creep in.”

Marked cards and stacked decks were common tools, and cheating was said to be rampant aboard many Mississippi River steamboats. One fanciful story depicts how Jim Bowie took pity on a young sucker from Natchez, Mississippi, who had lost all his money in a crooked game. Bowie joined the game, caught one of the cheats holding six cards and raked in a $70,000 pot, giving $50,000 to the man from Natchez and keeping $20,000 for himself.

Despite its ugly beginnings, poker soon earned respectability. If the Civil War made baseball America’s pastime, it didn’t hurt poker, either. Soldiers from both North and South played poker often during the war, although many would throw away their decks before battle, considering the cards “instruments of the Devil.”

In his 1872 treatise, Draw Poker: Rules for Playing, Gen. Robert “Poker Bob” Schenck wrote, “The three main elements of success in the game are: (1) good luck; (2) good cards; (3) plenty of cheek; and (4) good temper.”

Cheating, however, remained a factor, even if the methods were crude. Hickok, for instance, once caught a man replacing cards he had been dealt with those he conveniently dropped in his hat on his lap. Hickok won the pot by pulling his revolver and announcing that he was calling the cheater’s hand in his hat. Not that Wild Bill was beyond ungentlemanly card manners himself. Fellow gamblers often rebuked him for looking at the deadwood—the nickname for discards in draw poker.

Westerners go all-in

By the end of the Civil War, poker had plenty of fans, especially out West.

As Bat Masterson put it: “Gambling was not only the principal and best-paying industry of the town at the time, but it was also reckoned among its most respectable.”

Poker’s popularity even spread to the Apaches, who painted images on deerskin and hides for a 40-card deck, and Geronimo is said to have played poker in the 1890s. In 1880, attorney/actuary John Blackbridge lauded draw poker “as the most interesting game of cards that the human mind has yet produced.”

Gambling dens ran the gamut. Sporting crystal chandeliers, mahogany poker tables and rosewood-framed faro layouts with ivory counters, Luke Short’s White Elephant Saloon in Fort Worth, Texas, earned Masterson’s praise as “one of the largest and most costliest establishments of its kind in the entire southwest.” When the opulent Broadmoor Casino opened in 1891 in Colorado City, Colorado (now part of Colorado Springs), it attracted more than 15,000 gamblers daily.

Other dens, however, resembled the one Louis Rosche saw in Fort Benton, Montana. “The place was foggy with smoke and smelled of sweating, unwashed bodies and cheap whiskey,” Rosche said. “The floor was filthy. The male customers, nearly all of whom chewed, were remarkably bad marksmen. The spittoons, placed at strategic locations, all went unscathed.”

In 1867, Hoyle’s Games mentioned that the straight (or “sequence” or “rotation”), flush and ante had been added, although this varied regionally. “Straights are not considered in the game,” The American Hoyle had noted in 1864, “although they are played in some localities, and it should always be determined whether they are to be admitted at the commencement of the game.”

Variations of poker also became popular after the introduction of the 52-card deck, and, by the 1870s, wild cards (poker borrowed the joker from euchre). Stud poker, with four of five or seven cards dealt face up, was considered a “cowboy game,” although it originated in the mid-1800s in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. Draw poker superseded “straight poker,” the early “bluff” game that did not allow drawing cards, while “whiskey poker,” which included an extra hand dealt on the table (a “widow”), was, as The American Hoyle stated, “an amusing game.”

The names of gamblers were equally amusing. The Dodge City Times dubbed Masterson “The Boss Gambler of the West” in 1877. Redheaded Lottie Deno picked up the moniker “Lotta Dinero” in Fort Griffin, Texas. Then there were “Trick” Brown … “Offwheeler” J.J. Harlan … “Bones” Brannon … “Three-card Johnny” Gallagher … “Square Sam” Bonnifield … “Madame Mustache” Eleanore Dumont … “Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce” O’Rourke … “Diamondfield Jack” Davis … “Swiftwater Bill” Gates of the Klondike, who was so ruthless, “If his grandmother was holding a pair of tens and he had four aces he would sandbag her” … and “Poker Alice” Ivers.

Born in England in 1851, Ivers came to America in the 1870s and took to gambling to support herself after her first husband, Frank Duffield, died in a mining accident in Lake City, Colorado. She had more success at poker than she did at marriage (wedded twice more). Ivers smoked cigars, drank whiskey and cussed a blue streak, but she never gambled on the Sabbath. She earned a reputation as an excellent card player in Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Kansas, Indian Territory and the Dakotas, where she ran an illegal roadhouse near Sturgis when in her 70s. “At my age I suppose I should be knitting,” she said. “I would rather play poker with five or six experts than to eat.”

Reformers eventually shut down her roadhouse, forcing her into retirement. When Alice Ivers Duffield Tubbs Huckert died in 1930, a South Dakota newspaper reported, “Death, dealing from ‘a cold deck,’ flipped the ace of spades for ‘Poker Alice’ Tubbs yesterday. It was her admission card to the big game that is eternity.”

Gambling reform

Reformers, of course, would take poker out of the public places, although in 1911, California’s attorney general ruled that while stud poker was a game of chance, thus illegal, draw poker required skill and was beyond antigambling laws.

The territorial governments of Arizona and New Mexico prohibited all forms of gambling in 1907 to increase their chances at obtaining statehood. Even Nevada, which was admitted to the Union in 1864 with a state constitution that legalized gambling, closed its casinos in 1910 before allowing casino gambling again in 1931.

Although it would never be out of vogue completely, poker had hit a cold deck. Such is the way of the cards.

Bat Masterson knew that. In 1890, he wrote a friend: “I have been connected nearly all the time … in the gambling business and have experienced the vicissitudes which has always characterized the business. Some days—plenty, and more days—nothing…. I came into the world without anything and I have about held my own up to date.”

Masterson would leave the West’s poker tables and enjoy success as a New York sportswriter until his death in 1921.

But fortune frowned on others. Hickok wasn’t the only gambler to meet a violent death. In Fort Griffin, “Monte Bill” and “Smoky Joe” shot each other to death at a poker table amid accusations of cheating. Madame Mustache killed herself with poison in Bodie, California, in 1879. Suicide, in fact, became a frequent choice to exit life’s game.

Such was the fate of Pat Hogan, a noted gambler in Virginia City and San Francisco, who, as Bret Harte may have put it, “struck a streak of bad luck … and handed in his checks.” After Hogan killed himself in San Francisco, an ace of hearts was found among his possessions. Written on the card was this poker player’s lament:

“Life is only a game of poker, played well or ill; Some hold four aces, some draw to fill; Some make a bluff and oft get there; While others ante and never hold a pair.”

Johnny D. Boggs knows better than drawing to inside straights, so why can’t he win more at his monthly game?