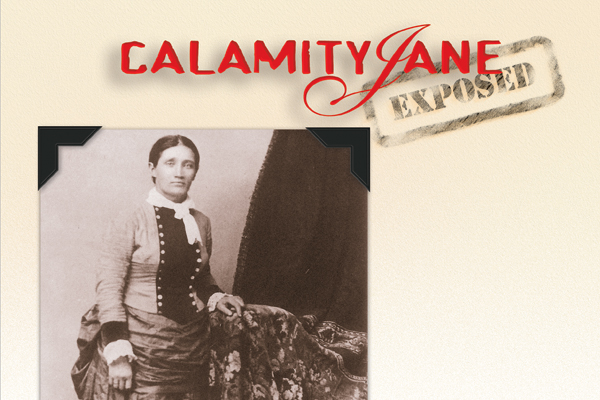

Her name isn’t real and neither are most of the folklore images of her.

Her name isn’t real and neither are most of the folklore images of her.

Calamity Jane—yes, there really was such a person in the Old West—wasn’t the glamour puss as Jean Arthur portrayed her in 1936’s The Plainsman, but she also wasn’t the silly twit of Doris Day’s 1953 movie.

She wasn’t “The West’s Joan of Arc” of dime novels or “The Black Hills Florence Nightingale” of early newspaper articles, nor was she the “Lady Robin Hood” of someone’s fantasies.

But she also wasn’t just a “whore” as some have tried to dismiss her.

Martha Cannary actually was a complicated woman who didn’t always buy into society’s constraints or sense of lady’s fashion—and therefore was suspect.

“In all the existing material written about Calamity Jane there is a remarkable hesitation to condemn her, in spite of the fact that her sexual irregularities and drunken escapades were prodigious and well-known,” biographer Roberta Beed Sollid says.

So it is no accident that HBO’s new hit, Deadwood, presents Calamity Jane as one of the few sympathetic characters.

And speaking of Deadwood—the real town in the mid-1800s—it’s eye-opening to see how Calamity Jane was regarded. In 1895, she returned to town after an absence of 16 years. Here’s how the Black Hills Daily Times reported it:

“She has always been known for her friendliness, generosity and happy cordial manner. It didn’t matter to her whether a person was rich or poor, white or black, or what their circumstances were, Calamity Jane was just the same to all. Her purse was always open to help a hungry fellow, and she was one of the first to proffer her help in cases of sickness, accidents or any distress.”

But after some townsfolk were “outraged” at such laudatory verbiage, the paper changed its tune, and a month later “atoned for its indiscretion by referring to Calamity as ‘a notorious ruin,’” Sollid notes.

That whiplash of impressions was common, she says, recounting why the rough-and-ready days of Deadwood’s boom suited this rough-and-ready woman who preferred men’s clothing:

“Her spasmodic generosity; her brusque, rough sympathy for the underdog; her failure to be impressed with riches, fine clothes or ‘society’; her lack of pretense or affectation of virtue; her complete rejection of simpering femininity, such attributes were esteemed on the frontier. She was a symbol of rough virtue—hardiness with a heart of gold and a lively sense of humor. Few who were anywhere near the scene of her activities were in the least deceived about her status as a kind of eccentric prostitute. Nowhere in the record is there approval of her aberrations but there is much support for the view that her virtues outweighed her vices.”

That helps explain why Deadwood gave her one of the biggest funerals in the town’s history, and The New York Times memorialized her as the “most eccentric and picturesque character in the West.”

Rough Beginning

Martha Cannary was born in 1856 (not 1852 as she claimed) in Princeton, Missouri. Her father was a gambler and her mother was “of the lowest grade.” The family moved to Montana Territory when Martha was a little girl and some say the parents abandoned their children. In her autobiography, Calamity intimates the family was together until her mother died in 1866, and then a year later, after having moved to Utah, her father died. She and her siblings went to Wyoming and after that, she makes no mention of her family. If she ever saw her sisters again, she never said.

Sollid says when the Union Pacific pushed through Wyoming in 1868, Calamity “began her life of following the construction camps.” If that year is correct, Calamity became a camp follower at age 12, but was passing herself off as 16. She always claimed that just two years later, she was a scout for the Army.

“Joined General Custer as a scout at Fort Russell, Wyoming, in 1870, and started for Arizona for the Indian Campaign,” says Calamity, in the autobiography she dictated to someone who knew how to write.

There are several big problems with that sentence, Sollid notes: Custer wasn’t in Fort Russell and never set foot in Arizona. In 1870, he was at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, writing his war memoirs.

Sollid says there’s no real proof Calamity was ever an employed scout or guide, although postcards showing her in those professions are on sale to this day in Western tourist shops.

What is clear is that she had to support herself most of her life. While she often hooked up with men, few supported her and the unions didn’t last long. She claimed to have married Clinton Burke in August 1885 in El Paso and then remained in Texas “leading a quiet home life” until 1889. Problem is, Sollid notes, Calamity wasn’t in El Paso in 1885 and is found throughout the West during the next few years. Later scholars have found a marriage certificate showing she was married to a railway brakeman she met in Wyoming, named Bill Steers. She had two children, a boy who died in infancy and a daughter who lived into the 1960s.

She earned her living for years as a bull-whacker, as she claimed, and some insisted she was outstanding when driving a team of horses. Whatever her skills with reins or a gun, newspapers throughout the West kept track of her comings and goings, showing that her movements were of interest to a general population.

That interest led to a short career in the limelight. When she appeared in Minneapolis in 1896—wearing buckskin trousers and boots with such high heels she could barely walk in them—the show was touted: “The famous woman scout of the Wild West. Heroine of a thousand thrilling adventures. The Terror of evildoers in the Black Hills. The comrade of Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill Hickok. See this famous woman and hear her graphic descriptions of her daring exploits.” How long that stint lasted and what happened to her in the next few years is unknown.

Her next venture into show business was in 1901 at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. At that time, Calamity was found living in Montana, “sick and half-dead from a long drunk,” Sollid reports. Calamity was talked into going East, promising not to take a drink without informing her chaperone, which didn’t keep her from drinking but did keep the chaperone hopping. Some reports say she “stole the show” on horseback, others say she drove a team of six horses. But this gig didn’t last long, either, and she made her way back to Montana.

From Martha to Calamity

There are many stories of how she got the name Calamity Jane.

An early one has her telling Jesse James it came because bad luck seemed to follow “Pretty Jane.” But in her autobiography, she claims she got it in the Indian Wars when she saved a captain during an ambush. Far more likely is that it just happened. “Jane” was a common name for any woman in the West—it was the name Lewis and Clark called Sacagawea—and her life was a calamity, compared to the life women were expected to pursue.

The name certainly fit perfectly into the fanciful dime novels that started appearing about her life in 1877. She was the heroine in perhaps 10 different novels by writer Edward L. Wheeler—all helped spread her reputation and made her a household name, even though the books were fiction.

But anyone who’s spent time trying to separate truth from myth about any Western icon shouldn’t be surprised that the same applied to this woman, who some applaud as living life on her terms in the honored tradition of individuality.

Jane and Wild Bill?

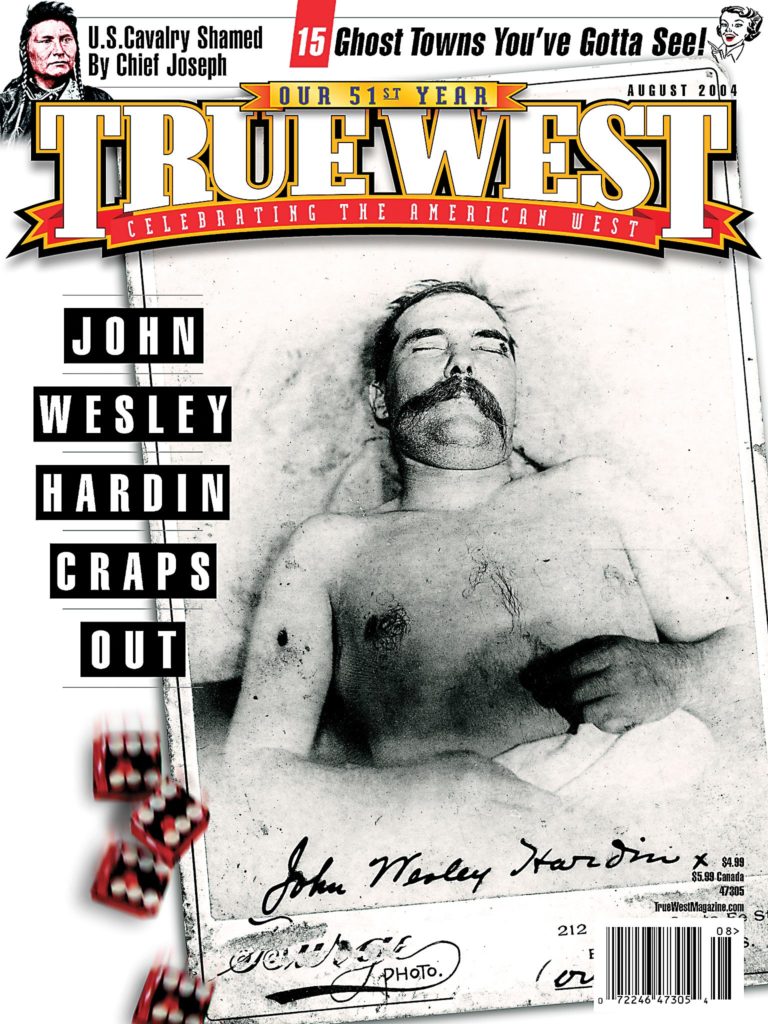

It seems she loved him fiercely, although Wild Bill Hickok didn’t reciprocate. They were, however, friends, and she would long mourn his murder on August 2, 1876.

But what she couldn’t get in life, she did get in death—ironically, dying exactly one day short of 27 years after him.

Calamity Jane is buried near Wild Bill in the Deadwood Cemetery. They are together in death, even if they were never really together in life.

And to this day, when anyone wants to represent the blunt grit of a woman of the West, Calamity Jane—real or imagined—comes immediately to mind.