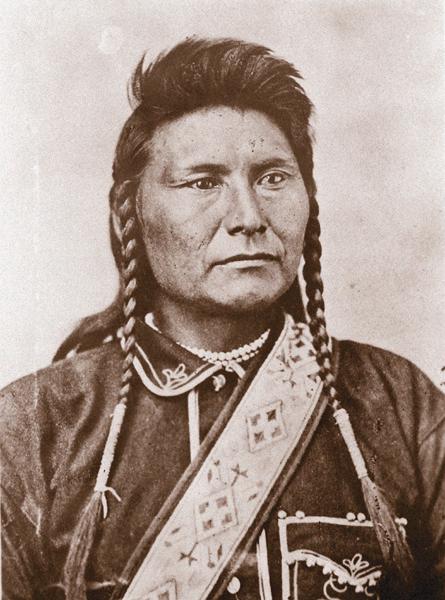

The words are as moving today as they were when Chief Joseph spoke them on a cold fall day in 1877:

The words are as moving today as they were when Chief Joseph spoke them on a cold fall day in 1877:

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are all dead…. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

On a harrowing journey estimated at 1,300 to 1,500 miles that summer and fall, the peace chief and some 750 Nez Perce—perhaps a third of those warriors—had fought for freedom, outmaneuvering and outfighting more than 2,000 soldiers and civilians in 20-odd engagements across the Rocky Mountain West. But it all ended less than 40 miles from the Canadian border, and safety.

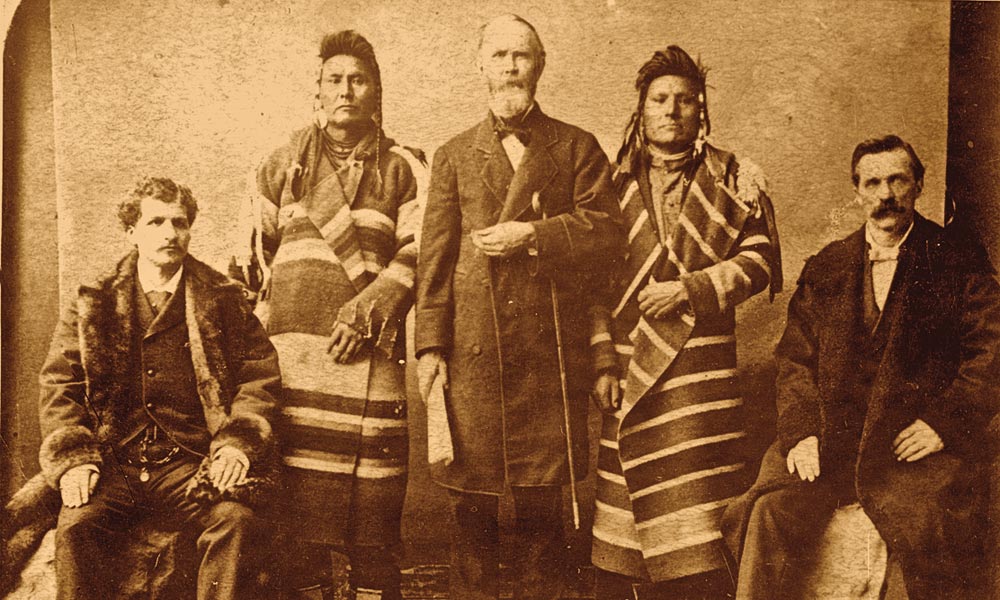

Joseph was perhaps the greatest Indian orator of his time. Consider his words during an 1879 trip to Washington, D.C.: “I want the white man to understand my people. Some of you think an Indian is like a wild animal. This is a great mistake.”

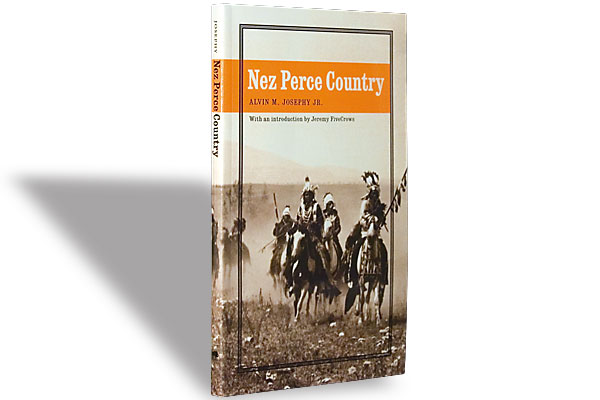

Well, one of the best ways to understand Joseph and his people is to follow the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail, established in 1986 to honor that tragic flight for freedom. Keep in mind, however, that the trail’s not for everyone. At 1,170 miles through Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming and Montana, it’s exhausting just maneuvering the winding roads and spectacular—often overwhelming—scenery.

The Beginnings

The trail starts at beautiful Wallowa Lake in Northeastern Oregon. The drama began unfolding here in May 1877 when all non-treaty Nez Perce were given 30 days to move to an Idaho reservation. Joseph’s appeal for more time to round up livestock and allow the Snake River, high with spring runoff, to become less treacherous was denied, and his band lost a lot of animals crossing the Snake and Salmon Rivers before meeting other Nez Perce at Camas Prairie.

Tensions heightened, for not everyone wanted peace, and on June 14, some warriors went on a vengeance raid. General Oliver O. Howard’s troops moved in to stop the bloodshed and force the Nez Perce to the reservation. At White Bird Canyon on June 17, a volunteer fired his weapon (the reasons are unclear) and the Nez Perce War was on. Thirty-four soldiers were killed before the army retreated. More bloodshed followed, and at a council in July, Looking Glass persuaded the Nez Perce to head for Montana, where they would join their Crow friends. Later, the Nez Perce realized their only hope for peace was to join Sitting Bull’s exiled Sioux in Canada.

From the Chief Joseph monument, site of Joseph’s father’s grave, the Nez Perce Trail crosses into Idaho at Dug Bar in Hells Canyon National Recreation Area, where Joseph’s band likely forded the Snake River. If you’re traveling by car, however, head north to Lewiston, Idaho, and east to Spalding.

Across Idaho

Nez Perce National Historical Park has 38 sites in Northeastern Oregon, North-central Washington (Chief Joseph is buried near Nespelem on the Colville Reservation), North-central Idaho and Western Montana. Some are well-marked; others are easily missed. So pick up a map at the park headquarters in Spalding.

From Spalding, drive south on U.S. 95—the circa-1874 St. Joseph’s Mission at Slickpoo (seven miles south of Lapwai) is a good place to stretch your legs—to sites of the July 3 and 5 skirmishes at Cottonwood, the Camas Prairie (six miles south of Grangeville) and the White Bird Battlefield.

The White Bird site has an interpretive shelter full of cyclists taking a breather when I stop on a windy June morning. You can’t blame anyone for stopping—especially cyclists on this roller-coaster road—to marvel at the panoramic view. For a closer look, the battleground also offers a seven-stop auto tour.

From White Bird, I double back up U.S. 95 to Grangeville, then head east and north on winding, rural state Highway 13 to the Clearwater Battlefield, an indecisive skirmish on July 11 between Howard’s troops and the fleeing Indians along the Clearwater River and overlooking bluffs.

At Kooskia, head east on the Lewis and Clark Highway, a.k.a. U.S. 12, toward Missoula, although you may want to take a quick trip west to East Kamiah, where another interpretive shelter chronicles the Nez Perce “Heart of the Monster” mythology (they sprang to life from drops of blood squeezed from the monster’s heart).

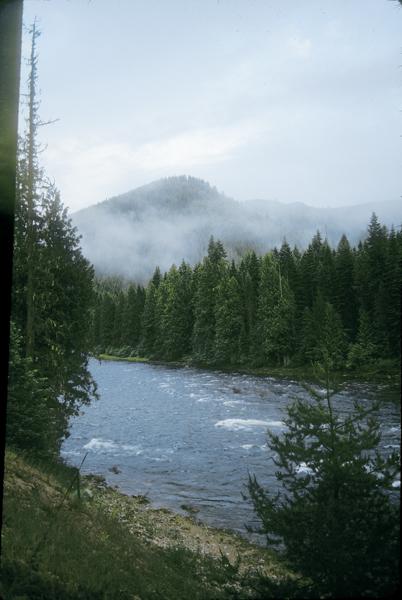

From Lowell, U.S. 12 follows the Lochsa River toward Lolo Pass. The Lolo Trail crosses the Clearwater Mountains several miles north of the highway. Long before the Nez Perce used this breathtaking (and likely backbreaking) trail to enter Montana, Lewis and Clark followed it in 1805-06.

Montana and the Big Hole

From Lolo, Montana, I head south on U.S. 93 through the Bitterroot Valley, where white settlers, fearing for their lives, took shelter in forts while the Indians passed through. On the North Fork of the Big Hole River, the Nez Perce and army clashed again, and the fight is commemorated at Big Hole National Battlefield off Montana Highway 43. (This year’s event is August 8.)

Looking Glass thought Howard’s troops were too far behind—a mistake he repeated often—so he did not post any sentries when the Nez Perce made camp. What he didn’t realize was that Col. John Gibbon’s Seventh Infantry had joined the pursuit. Gibbon’s troops planned a dawn attack on August 9 but lost the element of surprise when a lone Indian was killed while checking his horses. When the battle ended the following day, Gibbon had suffered 69 casualties—29 dead—while the Nez Perce had lost between 60 and 90 dead, most of those women, children and elderly.

Take in the 18-minute video at the visitor center, and don’t forget insect repellent, not to mention helpful trail brochures, if you tour the battlefield, which is worth fighting pesky mosquitoes to see.

From Big Hole, I stop at Bannack State Park, the first territorial capital of Montana and a well-preserved ghost town, and also the semi-touristy Virginia City, where Howard was forced to go for supplies after the Indians crossed Targhee Pass.

On to Yellowstone

At Camas Meadows, near Island Park Reservoir off U.S. 20 in Idaho, the Nez Perce bought time by stopping Howard’s advance on August 20 when they stole more than 200 horses and mules. From there, the Indians moved into Wyoming through five-year-old Yellowstone National Park. William T. Sherman was vacationing at the park when the Nez Perce passed through. The West Yellowstone-Cooke City Trail, by the way, isn’t well-marked in the park, which is worth exploring for a day or a week.

Then, via a roundabout route through Wyoming and Montana, it’s north to Laurel, off Interstate 90, where a life-size statue of Chief Joseph stands in Fireman’s Park. Seven miles north of town, a small marker commemorates the Canyon Creek battle. On September 13, Col. Samuel Sturgis’ troops were defeated in a brief skirmish by the Nez Perce rear guard that allowed the fleeing Indians to reach the high plains north of the Yellowstone River.

By now, the Nez Perce realized their Crow allies had no intention of helping them. Instead, the Crows harassed the Indians on horse-stealing raids. Thus, Chief Joseph’s people began the last leg of their journey, heading for Canada. Realizing their intentions, Howard sent dispatches to Col. Nelson A. Miles at Fort Keogh, asking him to intercept the Indians before they reached Sitting Bull.

East of Laurel, I rest in Billings—check out the Western Heritage Center—before heading north on U.S. 87 to the Musselshell River and west on U.S. 12. At Harlowton, I turn north on U.S. 191, then it’s back east through Lewistown and on to Cow Island Landing Recreation Area. The Nez Perce crossed the Missouri River here and headed toward the Bear Paw Mountains.

Last stop: Bear Paw

North of the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, I enter the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation on Highway 66, then head west on U.S. 2 toward Havre, stopping in Chinook at the Blaine County Museum before driving into Bear Paw Battlefield National Historic Park.

The park is undeveloped, with a few hiking trails and markers, making the Blaine County Museum, with its excellent audiovisual presentation about the Nez Perce, a must stop.

At Bear Paw, Looking Glass let his people rest, not realizing the danger of Miles’ command. Miles attacked on September 30, scattering the bulk of the Indians’ horses but suffering 50 casualties. By the time Howard arrived on October 4, the battle had become a siege.

Although White Bird managed to escape to Canada with about 200 followers, Chief Joseph remained behind. Most of the other leaders, including sniper victim Looking Glass, had been killed, and on October 5, Joseph surrendered.

Bear Paw Battlefield gets few visitors. There’s only one other tourist there when I arrive on a late afternoon—and one aggressive Northern Harrier Hawk. Harriers are overly protective of their nesting grounds, a marker warns me as I duck to avoid getting my hat, or head, ripped off. The National Park Service might consider placing that warning a little closer to the trailhead.

Although the trail ends here, the story doesn’t.

Terms of the surrender were disregarded. Instead of allowing the Indians to return to Idaho, the Nez Perce were sent to present-day Oklahoma, where they remained until 1885. Joseph and about 150 followers were transferred to the Colville Reservation in Washington, where they were met by Indian resistance. Others went to Idaho. Chief Joseph continued to fight for relocation to Idaho, but to no avail. He died on September 21, 1904—according to Nez Perce tradition—of a broken heart.

Chief Joseph’s words echo through my mind as I drive away.

“Whenever the white man treats the Indian as they treat each other, then we shall have no more wars. We shall be all alike—brothers of one father and one mother, with one sky above us and one country around us, and one government for all.”

Johnny D. Boggs is a novelist and freelance writer and photographer in Santa Fe.

Photo Gallery

– By Johnny D. Boggs –

– True West Archives –

– By Johnny D. Boggs –

The Nez Perce crossed the Bitterroot Mountains, on the Montana/Idaho border, in three days during their flight to Canada. With the Indian men were women, children, lodges and possessions. (By comparison, it took a trained army of soldiers two weeks to accomplish the same.) The strength and endurance of such a feat lends itself to the greatness of the Appaloosa horse.

The Nez Perce started acquiring their horses in 1710. They focused rapidly on selective breeding of the spotted horse and developed a superior breed, which is confirmed in the journals of Meriwether Lewis on February 15, 1806.

French Canadian fur traders traveling through the Snake River country followed a stream with green meadows and rocky basalt outcroppings to its confluence with the Snake. They called the stream the Pelouse. The Nez Perce called this area Peluse, meaning something sticking out of water.

As homesteaders and farmers moved into this land in the 1870s, they referred to the spotted horses as Palouse horses. Then came the saying of a Palousey horse. Soon it was passed on as an Apalousey horse. Eventually, the spelling of Appaloosa was preferred according to the Appaloosa Horse Club, which formed in 1938 to promote and preserve the breed.

In 1995, the Nez Perce Horse Registry program was started in Lapwai, Idaho, under the jurisdiction of the Nez Perce tribe. This program is for the promotion of equine study and horsemanship for youth. Four donated Akhal-Teke stallions and 33 Appaloosa mares were purchased to establish this breed to represent the Appaloosas that were originally bred by the Nez Perce. The stallions are of desert descent and known for incredible endurance and intelligence.

—Ron Maulding

– Courtesy Nez Perce National Historic Trail in Orofino, Idaho –