Of all the scams coming out of the Western mining era, the one perpetrated by George Babcock wins hands down.

Of all the scams coming out of the Western mining era, the one perpetrated by George Babcock wins hands down.

In 1894, Babcock, who was a jovial man of immense proportions, was working in Phillipsburg, Montana, when he heard about gold discoveries on nearby Rock Creek. Quitting his job, Babcock took his savings and rushed to the area, but he was disappointed to learn that the majority of the working mines were yielding only a modest return, while most were worthless.

The “Golden Scepter,” which had gold assaying at $20 a ton, did interest him. He bonded the property, scooped up an ore sample and, leaving a friend in charge, headed east to raise investment capital. Eventually, he met H.C. Quigley, a Delaware hardware millionaire. Babcock, of whom it was said could “talk the hind legs off a donkey, which was why there were so many two legged asses walking around,” had no trouble persuading Quigley that although the assay was on the low side, there was a whole mountain of the ore that was easily available.

Quigley brought his friends in. Jeremiah Colman, the mustard king, and Sen. Isham Harris of Georgia invested heavily. It was rumored that even President Grover Cleveland invested $25,000 or more. A company was formed, with Babcock at its head, and he hastened back to complete the purchase of the mine.

On his arrival, he was shocked to learn that the vein of ore had pinched out, but giving back the money didn’t even cross Babcock’s mind. He immediately employed an army of miners.

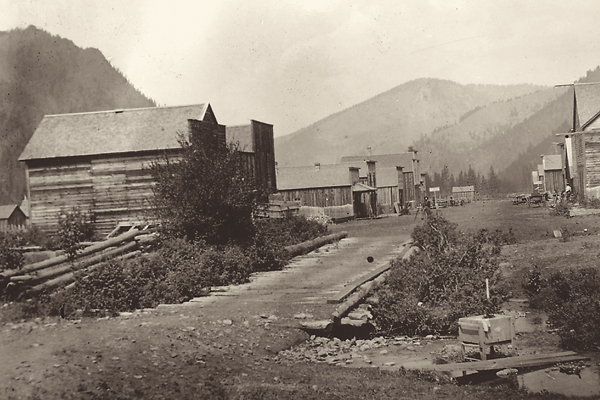

Even if the ore was useless, as long as Eastern money paid their wages, they would keep digging. Construction started on a 10-stamp mill, an electric generator was built and a railroad bed was laid six miles north to the main Northern Pacific lines. Soon, a town developed, which, with a touch of irony, Babcock named Quigley. Population soared to several hundred. Babcock even had mine workers build him an elaborate stone mansion on the outskirts of town.

Investors were sent glowing progress reports. The mine shaft was down 100 feet, and the ore stockpiled, awaiting completion of the mill and the arrival of the railway.

It wasn’t until August 1896 that the bubble burst. Company shareholders demanded a return and insisted that some of the ore that had been mined be shipped to smelters in Butte. It was over. With no more wages, the miners left, followed by the merchants, and within a month, Quigley was a ghost town. “Old Babb,” as he became known, wandered back to Phillipsburg and died penniless a few years later, maintaining to the end that had the mine been developed a little further, he would have struck it rich.

As it turned out, he was right. Several years later, the Alps Mining Company acquired the property and just below the 100-foot mark, encountered gold that assayed at $200 per ton. The mine operated successfully until 1930.

Terry Halden, a member of Western Writers of America, resides just above the Medicine Line in Alberta, Canada, and is a self-proclaimed ghost town nut.