May 27, 1837: A son, James Butler, the fifth child was born to William Alonzo and Polly Butler Hickok of Homer (later Troy Grove), Illinois.

May 27, 1837: A son, James Butler, the fifth child was born to William Alonzo and Polly Butler Hickok of Homer (later Troy Grove), Illinois.

1856: Nineteen-year-old James Butler Hickok left the family home with brother Lorenzo, heading for Kansas Territory to farm; Lorenzo soon returned to Illinois.

1858: James became a constable in Monticello Township, Johnson County, Kansas, remaining a short time before hiring on as a teamster for Jones and Cartwright, for whom he worked until 1861.

Spring 1861: James took a job at Rock Creek Station in Nebraska Territory. It is a position that changed the course of his life and where we begin this Renegade Road.

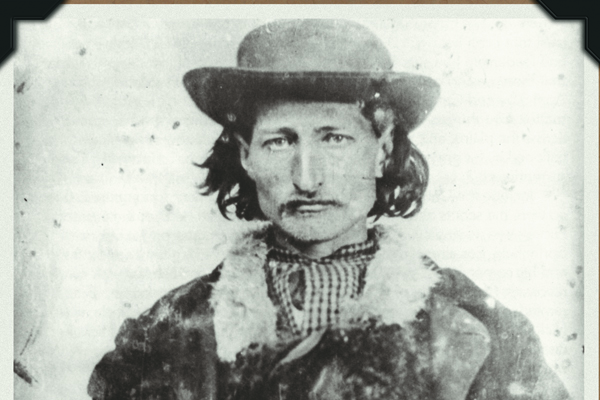

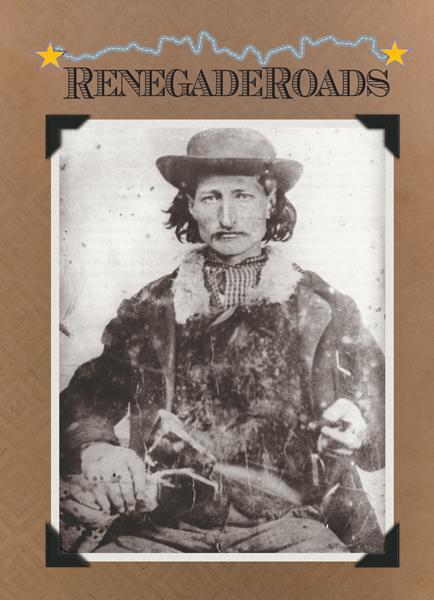

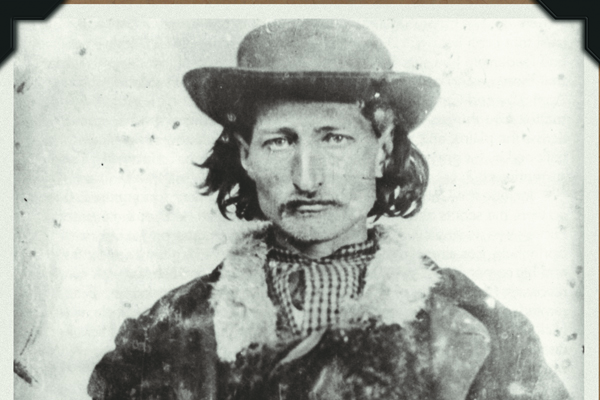

A gunman born

Tens of thousands of travelers headed toward Oregon and California after 1841, passing the site that evolved into Rock Creek Station. When Hickok found work there, the station served the Pony Express and general travelers. He already went by the nicknames Bill or William, when, just two months after his arrival, he was involved in a shoot-out with station owner David McCanles. Those shots changed the course of Hickok’s life. He left Rock Creek Station soon after the killing, finding work as a wagon master, scout and courier with the Union Army during the Civil War.

Today, Rock Creek Station is a Nebraska State Historical Park, located just outside Fairbury. The park tells the story not only of Hickok’s killing of David McCanles but also highlights the Oregon Trail and use of the station by the Pony Express. You will find an original barn from Hickok’s era and recreated buildings showing how Rock Creek Station appeared when he worked there.

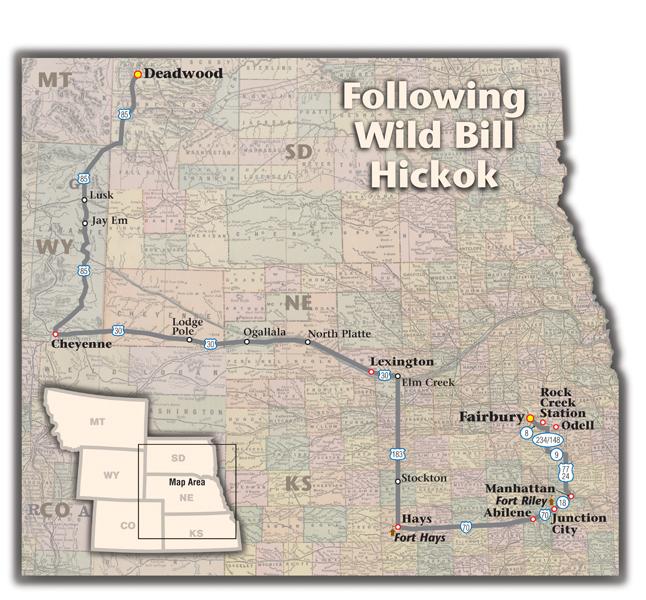

Although Hickok detoured to Springfield, Missouri (see SideRoad, p. 62), I stay west of the Missouri River. Just south of Fairbury, I?turn east on Route 8, passing the turnoff to Rock Creek Station. At Odell, I head south on Routes 234/148 into Kansas, east on Route 9 and south on U.S. 77 & 24 into Manhattan, then west on Route 18 to Fort Riley, Hickok’s next major work assignment.

A “special detective”

Early 1866: Hickok was appointed “special detective” at Fort Riley, authorized to find missing government property. Hickok also guided Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman over the Oregon Trail to Fort Kearny and Gen. John S. Pope along the Santa Fe Trail to Santa Fe.

Still an active military base and home of the First Infantry Division (The Big Red One), Fort Riley was founded in 1852 at the junction of the Smoky Hill and Republican Rivers. The soldiers stationed here initially protected travelers on the Santa Fe Trail and diffused tension during the early days of “Bleeding Kansas.” The fort later became a cavalry training center, a role it maintained into the 20th century.

Armed soldiers meet my car at the east entrance to the fort, inspect my insurance papers and driver’s license, and scrutinize my face before allowing me to pass onto the military reservation where I visit the First Kansas Territorial Capitol.

Hickok’s Hays City years

From Junction City (south of Fort Riley), I steer my Subaru onto I-70 and head west, where Hickok really cemented his reputation. To avoid backtracking across half of Kansas, I visit Hickok’s haunts out of chronological order, first stopping in Abilene and then continuing on to Hays and the site of Fort Hays.

During the late 1860s, Hickok served as an army scout and wagon master in Kansas. The open, rolling hills of Western Kansas undoubtedly appealed to his quest for adventure; he lived there more than once. He arrived the first time in April 1867, scouting for the Seventh Cavalry, commanded by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer.

In 1869, Hickok became sheriff of Ellis County in Hays City but was defeated during the election of 1870. Hickok left Hays City for a period, but he was back before year-end, engaging in a shoot-out with troopers from the Seventh Cavalry. He killed one and wounded another.

Four original buildings at Fort Hays, including the trader’s store and officers’ quarters, are restored as part of Historic Fort Hays. Most displays relate to the military occupation

of the fort, which was located at the junction of major military roads to Fort Larned, Fort Dodge and Fort Wallace. There is also information about freighting—Wild Bill’s occupation during much of his early life—and travel on the Smoky Hill Trail.

Hickok’s Theatrics

March 1871: Hickok relocated to Abilene, Kansas, an important stop on the Chisholm Trail. Here he became marshal for eight months, controlling Texas cowboys intent on shaking off the dust at the end of their long cattle trail. Cowboys weren’t the only rowdies Hickok contended with in Abilene. He also fatally shot Phil Coe and mistakenly killed his own deputy and friend, Mike Williams. From Abilene, Hickok moved to Kansas City, spending three years guiding, scouting and even acting in a theatrical group organized by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, whom he’d met at Fort Hays.

One of Hickok’s guns is on display at the Dickinson County Heritage Center in Abilene. The heyday of Abilene’s cattle era shows in the 1880 Lebold Mansion, now furnished with Victorian antiques. Hickok didn’t have the opportunity to purchase patent medicines from the Seelye Company, but you can see original samples of the company’s products before touring the Seelye Mansion in Abilene, an impressive residence that had not been built when Hickok was taming this cowtown.

Leaving I-70, I travel north on U.S.183 and turn west on U.S. 30 toward Lexington, Nebraska. You can take I-80, but I prefer the original Lincoln Highway that allows me to

pass through towns rather than whiz

by them at 75 miles an hour. Next stop: Cheyenne.

A marriage in Cheyenne

1874: Hickok abandoned his acting career with Buffalo Bill and moved to Cheyenne, Wyoming, for a short stay before spending some time in Kansas City and St. Louis.

1876: Hickok was back in Cheyenne on March 5 to wed Agnes Lake Thatcher, a circus performer adept on both the high wire and horseback. The two had met in Abilene in 1871. Following their marriage and honeymoon, Hickok left his bride with her family in Ohio and made his way with Charlie Utter to his final stomping ground: Deadwood, South Dakota.

The mansions of cattle barons that dominated 17th and 18th Streets in Cheyenne during the years Hickok spent in town are now part of the Rainsford Historic District. Various restaurants operate in two of the homes: Lexie’s Mexican Grill (my favorite) and the Whipple House. The Rainsford Inn, a fine bed and breakfast, is named for the architect of many homes in the district.

To really step into Hickok’s tracks, make your lodging destination the Nagle-Warren Mansion, where the gunfighter wed Agnes. Restored to Victorian elegance, the mansion features claw-footed tubs, ornate chandeliers and a bountiful breakfast. The Nagle-Warren is, without question, my favorite place to stay in Wyoming.

From Cheyenne, Hickok headed north to the Black Hills, ending up in Deadwood. Although he joined in some prospecting adventures with his partner Charlie Utter, Hickok spent most of his time at the card tables.

I leave Cheyenne and head north on U.S. 85, which parallels—and in some places, overlays—the Cheyenne and Deadwood Trails across Eastern Wyoming and into South Dakota.

Final stomping ground

August 2, 1876: Hickok was playing poker in the Saloon Number 10 in Deadwood when John “Jack” McCall shot him in the back of the head, ending the trail for Wild Bill, who was laid to rest in the Deadwood Cemetery.

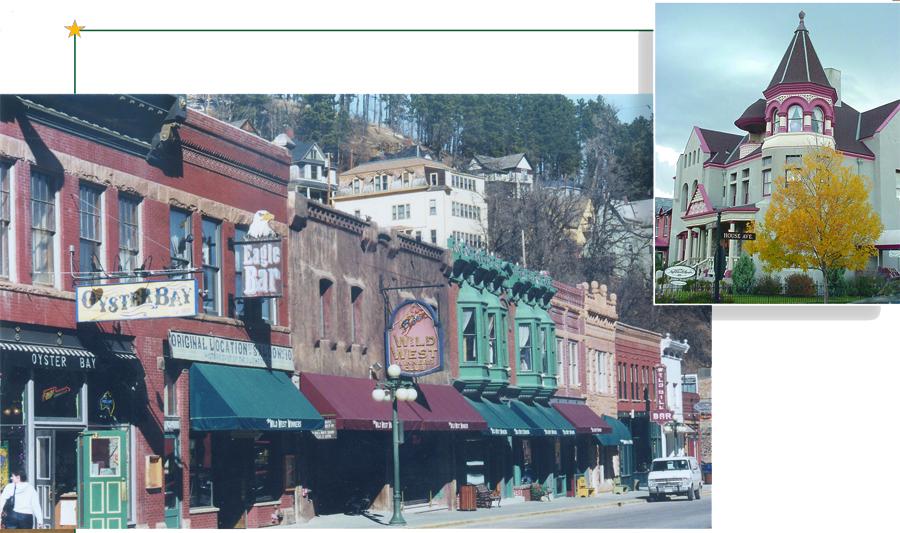

Pull up your own chair at a poker table in the Old Style Saloon Number 10 and have a shot of whiskey. Be sure to keep your back to the wall, as Hickok should have done. These days, the Number 10 pays a $250 bonus if you happen to hold aces and eights, which legend says Hickok was holding when he was killed.

At the Number 10, with its original bar and sawdust-covered floor, the locals know if you’re turning 21. Beware if the bartender tries serving you a Flaming Red Rooster. It’s a “nasty drink,” my 21-year-old son told me, assuring me he’s never had one, but saying his friends have imbibed. A cousin, whose in-laws own the Number 10, agrees. “I’m not even sure they serve it anymore,” she said, adding, “A Red Rooster makes you sick.” Neither knew exactly what’s in it, but one combination is hot sauce and Wild Turkey.

After you try your luck at the Number 10, eat a relaxing Italian or steak dinner and choose from the town’s best wine selection at the adjoining Deadwood Social Club. Then kick up your heels to live music or watch a show in the Charlie Utter Theater.

Hickok played his last poker hand in Deadwood, and I’ll end the trip here as well, letting you in on a little secret. It was fun to follow the trail blazed in the 19th century by my great-great-great-great uncle-by-marriage twice removed. Which really means, I’m not a lot closer relation to him than you probably are, but there is an Uncle Hick in my family tree and my Aunt Mallie most definitely was a Hickok. As far as I know, however, she never shot a gun or played poker.

When she’s not traveling throughout the West, Candy Moulton hangs her hat near Encampment, Wyoming.

Photo Gallery

– By Candy Moulton –

– True West Archives –

– Nagle-Warren photo by Ryan M. Conway / Wyoming Tourism; Deadwood photo by Candy Moulton –