It’s a breathtaking scene in a beautiful movie.

It’s a breathtaking scene in a beautiful movie.

Hundreds of wild horses run free across the Montana prairie in the final scene of Hidalgo. The spectacular sight lasts only four minutes in the film. But those four minutes took more than a month of preparation.

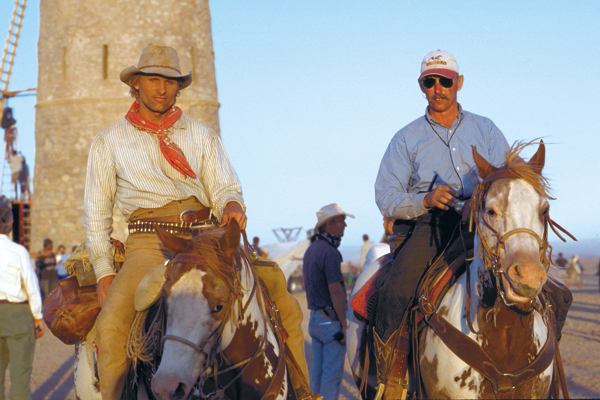

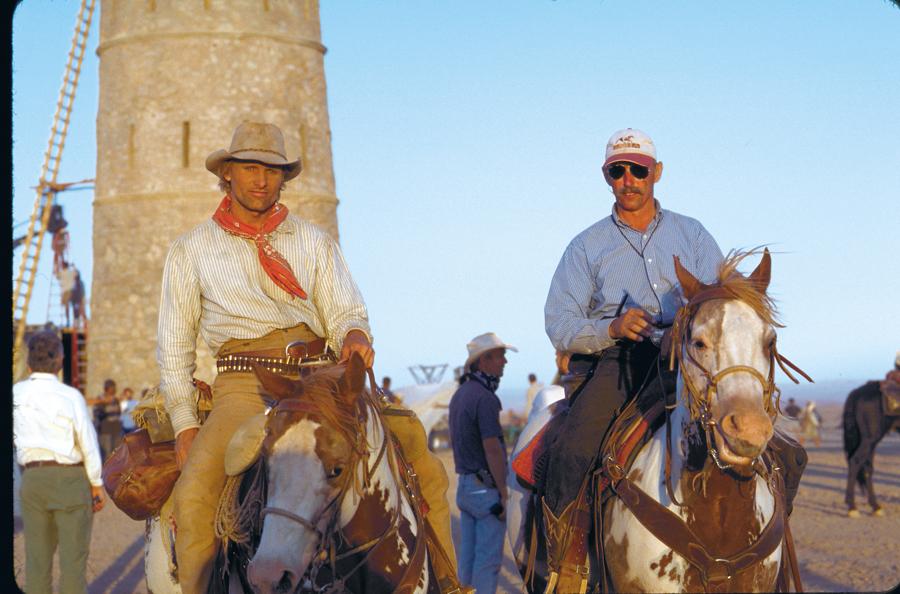

“It was a very big undertaking to run all those loose horses,” Rex Peterson recalls. “Several people said you’re crazy to even try that!”

Peterson was the head horse trainer for Hidalgo, an assignment so tough it put him in the hospital not once, but twice. The movie tells the story of endurance rider Frank T. Hopkins, a half-breed American cowboy who takes his paint pony Hidalgo to the deserts of Arabia to run a 3,000-mile race for a $100,000 purse.

It’s not certain how much of that story actually happened, but the ordeal of training the horses for the movie makes for quite a dramatic story in itself.

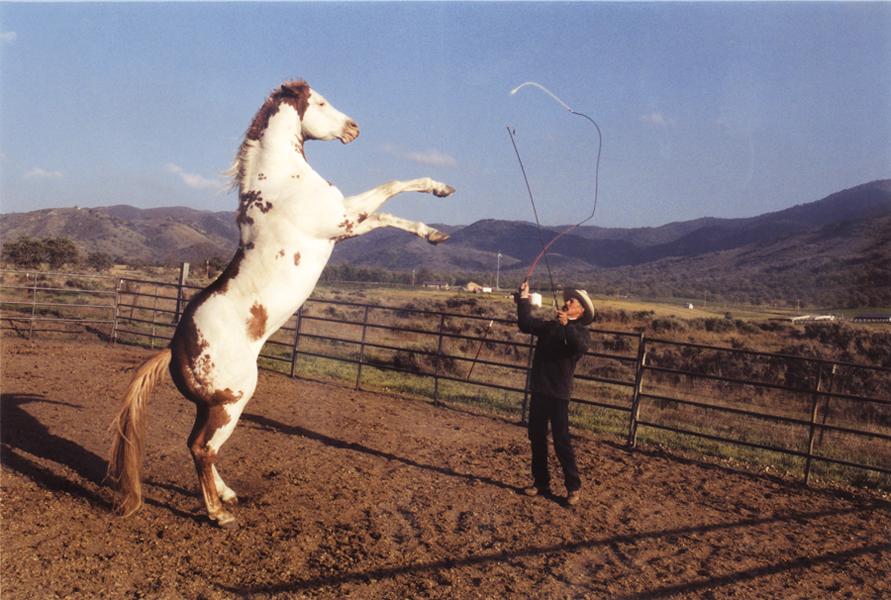

For Peterson, that tale began on a ranch in Nebraska, where he grew up trick riding and roman riding at rodeos and Wild West shows. It was through one of those Wild West shows that he met Glenn H. Randall, the legendary horseman who trained horses for Roy Rogers’ films, Ben Hur and countless other movies and TV shows. “He was a master horseman,” declares Peterson. “There’ll never, ever be one like him.”

Randall died at the age of 84 in 1992. Peterson spent 15 years working and studying with him, and still gives Randall credit for all he’s accomplished. Now after 28 years in the business on films such as The Horse Whisperer, Black Beauty and Runaway Bride, the 50-year-old Peterson is arguably Hollywood’s top horse trainer. And that stampede of 570 horses at the end of Hidalgo is part of the proof.

Shot on Montana’s Blackfoot Indian Reservation, it’s the biggest loose horse stampede ever filmed, without a fence or wrangler in sight. It’s a scene other filmmakers have attempted but have never been able to do. And while Rex is the guy who made it happen, he gives credit to his crew. “My guys in Montana probably spent six weeks on the phone gettin’ things lined up…. We had four days to shoot it, two weeks to get the horses in the corrals … two weeks to prep ’em.”

Most of those horses belong to people on the reservation. But not just any horse would do. The horse playing Hidalgo is a stud and there could be no others in that herd. “So they’re all mares, geldings and colts,” Peterson says. “And then [we] had to make sure we had nothing in there that was lame or injured in any way.”

Each horse also had to be identified, so there’d be no ownership disputes after the filming was over. But before it could begin, the horses had to be trained to run together. “We started drivin’ ’em in small groups and then started addin’ until [we had] 50, 100, 150, 200,” Rex recalls. “We never had the whole 570 out together until the day of filming.” Twelve takes later, Director Joe Johnston had what he wanted.

But just how Peterson pulled this off remains something of a mystery. “Everybody in the movie business wants to know how we done it,” Rex told a Great Falls newspaper. “And I ain’t going to tell them.”

Doing the impossible is Peterson’s job description. And on this film it began with the search for the horse that would play Hidalgo. The writer wanted a mustang. The director needed a gelding or stud no bigger than 15 hands. Rex persuaded them to take a paint. Sorrel and white was the agreed upon color. But then Peterson had to search the country to find the right one, and he had only seven weeks to do it.

The trainer scoured the internet, spent thousands of dollars on the phone and lived on airplanes, sometimes hitting 15 airports in a weekend, as he searched for what he thought Director Johnston wanted. But stacks and stacks of photographs were rejected. “I’m taking pictures back and Joe’s goin’ through ’em and not likin’ anything! I’m pullin’ my hair out!”

Peterson finally stumbled onto T.J., the paint that became Hidalgo, by accident. He was in Michigan, photographing other horses, when an owner showed him one last stud that Rex snapped with the last picture on his roll of film. That was the one Johnston liked.

Just finding the horse doesn’t mean your troubles are over. Once owners discover you’re buying horses for a movie, the price often goes up. “I went and looked at a horse in Kentucky,” he recalls. “When I left here [L.A.], they wanted $5,000. When I got to Texas to look at a horse, they wanted $15,000. When I got to Kentucky, they wanted $25,000.”

So Peterson does his best to keep his intentions a secret.

Despite those challenges, Peterson soon had T.J., his primary backup horse R.J., three other horse doubles and seven weeks to train them. But no two paints look exactly alike. And making these five horses match for the film was another nail-biter. A parade of hairdressers and makeup artists came and went. “We was goin’ through every makeup, every hair dye, everything possible to try to make it work,” Rex says. “And we were gettin’ down to the start of filming and didn’t really have a good idea of how to do it.”

But just in time, a makeup artist named Garrett Immel came up with a nontoxic paint compound that worked perfectly. And by the end of the shoot, Peterson says you’d be hard-pressed to tell those horses apart.

But once one challenge was solved, another instantly took its place. Twelve horses were taken to Morocco for the movie, a third world country without any modern airport lift facilities to unload horse crates from an airplane. So six of the horses were flown to Europe, trucked across the continent, then sailed across the Mediterranean. But suddenly the other six were needed as well. The only way to get them to Morocco in time was on a Russian cargo plane with a ramp. That must have been quite a flight because Peterson won’t talk about it. “All I’ll tell you is it was an experience not to be forgotten and never done again.”

Once in Morocco, he had to keep the 12 American horses completely separated from the Moroccan mounts. He couldn’t even let the animals drink out of the same water tank because of the North African horse disease and other illnesses the animals carry. A veterinarian constantly monitored the horses, along with a representative from the American Humane Society, a presence the trainer welcomed. “If anybody was to make any accusations about the film, American Humane is there as an independent party,” Peterson explains. “So they can say, ‘No we were there, this is what happened.’”

No horses were injured while making the movie. Peterson wasn’t so lucky. He was riding a horse in a railroad boxcar when the animal somehow slipped, fell on the tracks and used Peterson’s leg for a cushion. That put him in the hospital the first time. Training trick horses is hard enough without having to do it on crutches. But he somehow got the job done. Peterson was back in the hospital after a bout of severe bronchitis from the Moroccan dust. When that illness hit him a second time, the production came home and finished up its desert scenes in California.

It all made for a very tough assignment. And we haven’t even mentioned all the tricks Peterson taught those Hidalgo horses, like when R.J. picks up star actor Viggo Mortensen by the neck of his shirt and drags him across the arena in the Wild West Show scene. “If that horse misses and doesn’t grab exactly … it’s gonna hurt! And it’s gonna hurt bad,” Peterson says. “But I had the right set of horses to do it.”

He trained at least two horses for every stunt in the movie. R.J. is in most of the high energy scenes. T.J. has the mellower disposition. Another horse named Oscar did the jumping. But whatever the trick, Peterson says the secret is to make it fun for the horses. “You gotta make it where they get where they enjoy it. Even grabbin’ Viggo and draggin’ him, I think R.J. thinks it’s a big game … that hey, this is fun.”

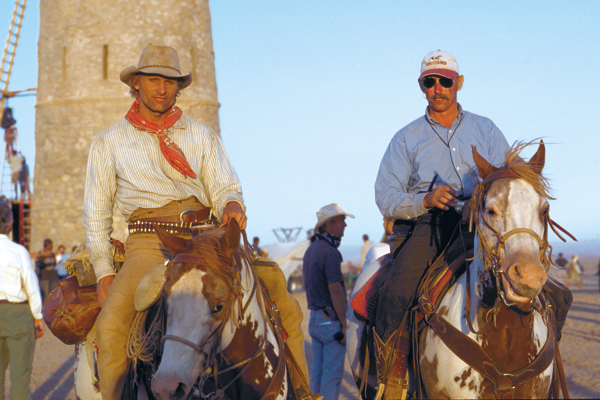

While it was a tough film for Peterson, he’d love to do another with what he calls one of the best cast and crew he’s ever worked with. And he’s quick to give credit to others for the thrilling horse scenes in the movie, like when a stuntwoman and stuntman leap on R.J. as he runs loose through a village as fast as he can. “It took horses that would stand bein’ jumped on…. It took a stunt girl to put the horse in position … it took an art director to design it. It took a d.p. [director of photography] to see the right way to shoot it … it took a director to tell him that’s what he wanted … and it took a writer to write a fabulous scene.”

It all adds up to a fabulous movie. Peterson has seen the reaction firsthand in Hollywood, where he brought T.J. to a theater, giving fans the chance to meet the famous horse in person. And while he’s gratified with the smiles of young and old alike, the one review he longs for is the one he will never hear. “I hope he’s up there watchin,” Rex shares. “I’m proud of what Glenn taught me [and] … without Glenn Randall … this film was impossible.”

Mark Bedor’s stories and photographs on the West have been published in Cowboys & Indians, Persimmon Hill, Western Horseman and other national magazines. He also writes for KCBS?TV?News in Los Angeles. E-mail him at markbedor@sbcglobal.net

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy Walt Disney Company unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Mark Bedor –