Mexican raiders swam across the Rio Grande, showing off their freshly-stolen beeves, taunting Capt. Leander McNelly and his Special Force of Texas Rangers to cross the river and invade Mexico.

Mexican raiders swam across the Rio Grande, showing off their freshly-stolen beeves, taunting Capt. Leander McNelly and his Special Force of Texas Rangers to cross the river and invade Mexico.

The rustlers knew the Neutrality Act of 1818 forbade American military expeditions into countries at peace with the United States. And in 1875, the U.S. and Mexico were at peace.

In fairness, the Mexicans did not recognize the border. Texans regularly raided into Mexico, stealing cattle, and the outlaws may have felt they were just giving a little tit for tat.

As McNelly saw it, his war was with the outlaws, not with Mexico, which was merely their hideout. So in November that year, he finally ordered his men to cross the border into Mexico, acting on a tip that thieves would be rustling cattle to fulfill an 18,000-head contract.

But the Rangers attacked the wrong ranch, shooting down innocent men. By the time they reached the intended bandit ranch, Las Cuevas, 250 Mexicans awaited them, on full alert. Outnumbered, the Rangers fled, only to encounter the ranch’s leader, Gen. Juan Flores Salinas, and his men. During the ensuing gunfight, Salinas was killed, though the two sides eventually negotiated a truce, which called for the Rangers to leave Mexico. The bandits returned 65 head of stolen cattle the following day, which McNelly’s men delivered to the rightful Texas owners.

“Tell them, Mr. Attorney General, that there was peace”

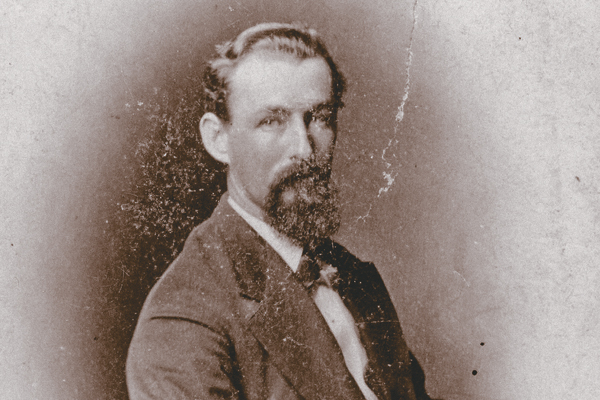

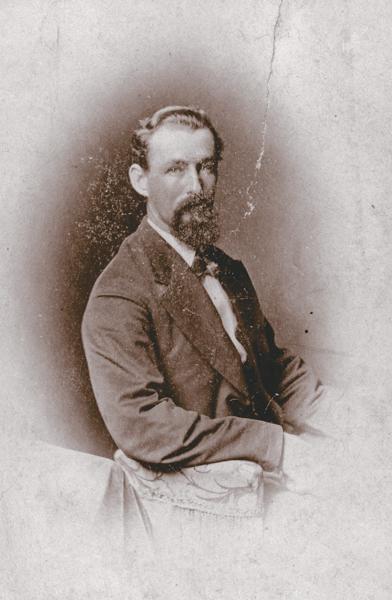

A former Confederate hero, McNelly had been sick with tuberculosis when Texas Gov. Richard Coke picked him to lead the Special Force of Rangers. Because McNelly died from the disease the following year, he never stood trial for his neutrality violation.

But 129 years later, McNelly’s actions have finally been aired in court. If the U.S. had charged him with violating the Neutrality Act, how would the captain have fared in court? A jury was asked to decide just that on May 8, 2004, in the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum’s theatre, which served as a courtroom for Baylor Law School’s mock trial.

A mock trial is a history lesson brought to life, meant to be an “informative and entertaining way of presenting our story to the public,” says Gerald Powell, Abner V. McCall Professor of Evidence at Baylor Law School in Waco, Texas (next door to the Texas Ranger museum).

The unscripted trial contained testimony based on witnesses’ congressional statements and other documents authored by them. But no documents directly addressed McNelly’s orders.

“Was he ordered to cross the river if he felt it necessary, or was that his idea?” defense lead counsel Powell says is the trial’s unresolved question.

What the evidence did show is McNelly disobeying repeated orders not to cross the border, a fact the prosecution made the crux of its case, claiming McNelly “alone” had decided what was good for the country.

But the defense insisted McNelly was a hero. Prior to the Ranger invasion, Adjutant Gen. William Steele had written to Gov. Coke that barring other measures, the person stationed at the Rio Grande should have the authority to pursue bandits across the river. And at the time, that person was McNelly.

Coke had given a similar order almost a year before McNelly was sent to the region. The governor gave state militia Capt. Refugio Benavides permission to cross the Rio Grande in pursuit of raiders, defending his order as one of necessity and self-defense. Minus a good spy network, Benavides never had the opportunity to cross.

Also admitted into evidence were documents of a border crossing that passed without penalty and occurred about two decades earlier. When Jack “Rip” Ford and his Rangers caught then-bandit leader Juan Cortina in the act of cattle rustling in 1860, they pursued him and his men across the border. The Rangers’ orders came from U.S. Army Maj. Samuel Heintzelman, whose federal troops weren’t allowed to cross the border. Authorizing the Rangers to cross was apparently left to Heintzelman’s discretion, and he wasn’t one to oppose the idea. McNelly, however, didn’t have a federal superior on his side when he crossed; or at least, there’s no known document to prove he did.

Because a case isn’t won on circumstantial evidence, the defense made its case by asking the jury to focus on the language of the Neutrality Act—especially the word peace. Was McNelly chasing people with whom the U.S. was at peace or outlaws using Mexico as their safe harbor?

“Ask yourself if there was peace on the Rio Grande Frontier,” argued the defense. “Read about the brutal murder of Thadeus Swift … the mutilation of his wife’s body by the knives of Mexican bandits. Tell their family, Mr. Attorney General, that there was peace in Refugio County in the summer of 1874.

“When Mexican raiders … murdered the post-master, J.L. Fulton, robbed his store, murdered his clerk, Mauricio Villanueva. Tell their families, Mr. Attorney General, there was peace in Hidalgo County in February of 1875.

“Read about the bold raid of over 100 miles into Texas, almost to Corpus Christi. Tell the Noakes family, Mr. Attorney General, that there was peace in Neuces County on Good Friday 1875.

“Tell the citizens of Corpus Christi that when they were in their churches that Easter morning, praying for deliverance from the raiders on the outskirts of town, tell them, Mr. Attorney General, that there was peace.”

Whether or not “there will be law and order along the Rio Grande”?is up to the jury, the members were told. If they decide a guilty verdict, they’ll be telling those on both sides of the river “maybe you better give up your hopes and your dreams … because the Mexican government can’t protect you, the U.S. government won’t protect you, and the Texas Rangers won’t be allowed to protect you.”

If those families were here today, they would have found a jury that recognized there was no peace along the Rio Grande, and that the region sorely needed McNelly’s Rangers to restore order. The defense’s argument won over the trial’s audience-jury, which returned with a verdict of 50 guilty and 163 not guilty. The judge declared McNelly “mostly not guilty.”

Although McNelly’s jaunt across the river didn’t end the cattle rustling, he did send the Mexican bandits a pointed message: no one taunted him and his Rangers and got away with it. McNelly could at least be satisfied that the stolen beeves had returned to graze Texas pastures where they belonged.

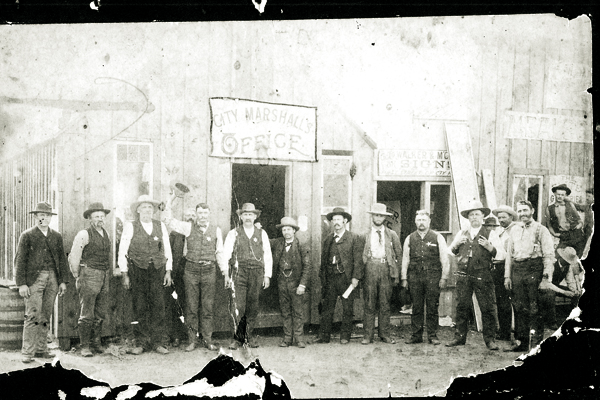

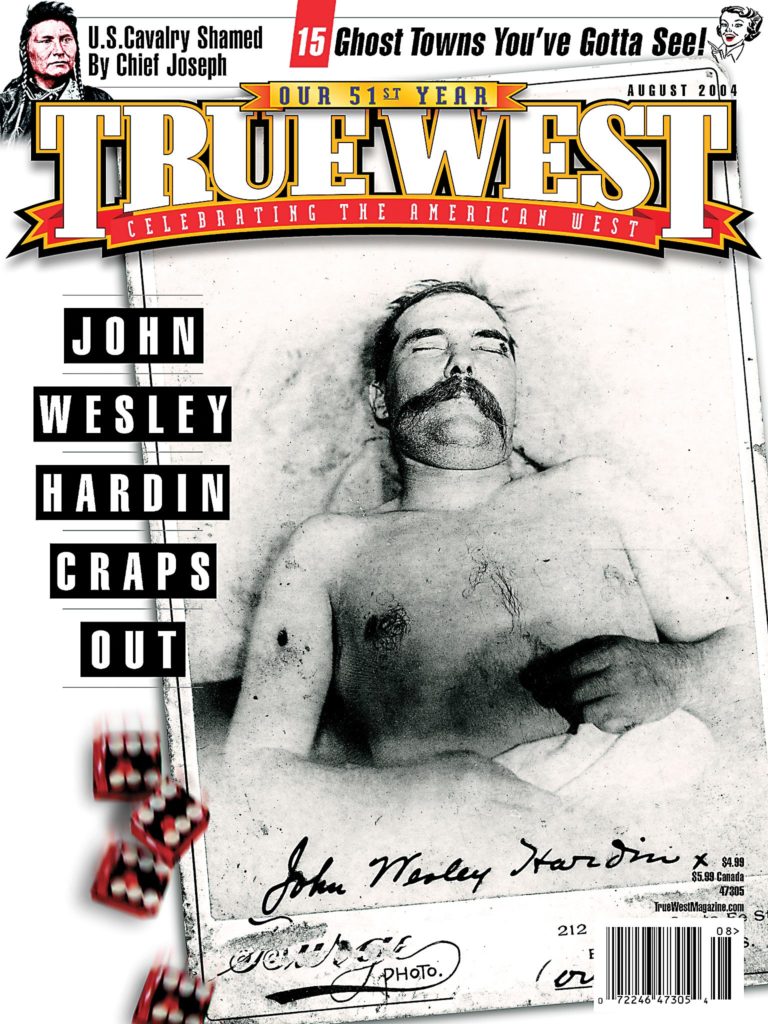

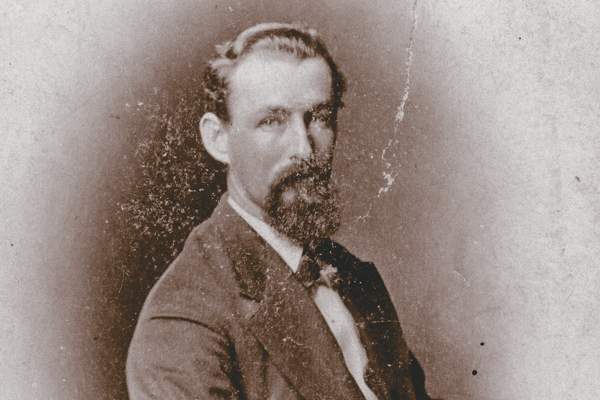

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

– Courtesy Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco, Texas –