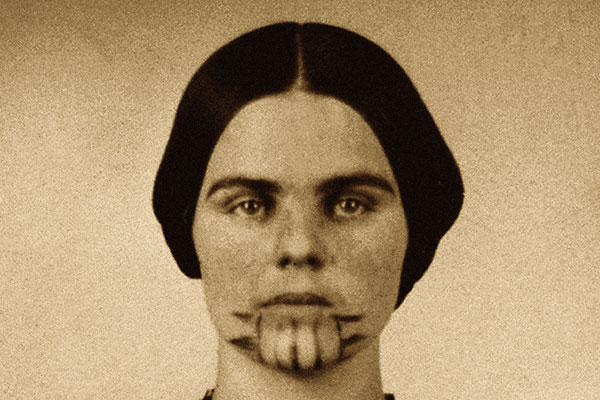

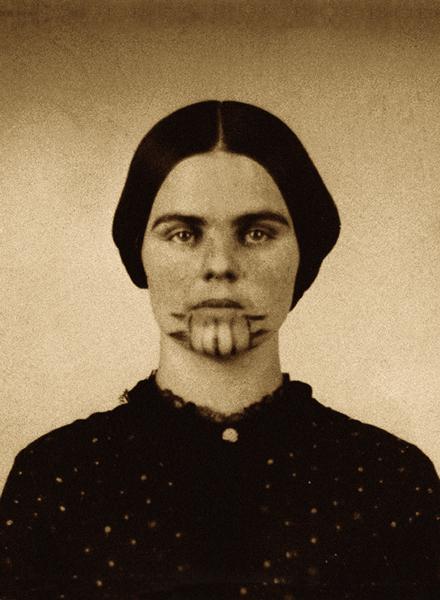

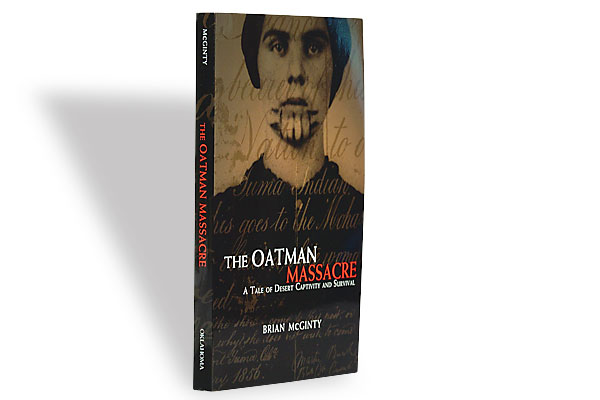

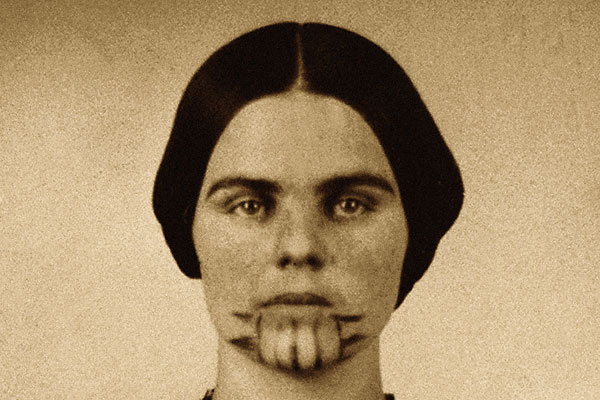

Olive Oatman was a 14 year old traveling west in 1851 when Southwest Indians attacked her family’s wagon train in Arizona (then Mexico), capturing Olive and her seven-year-old sister Mary Ann.

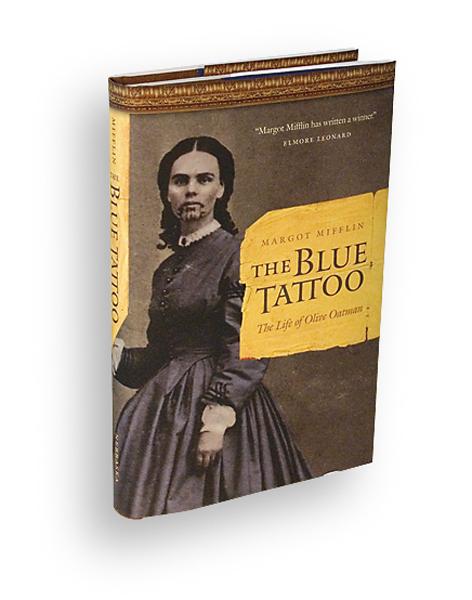

The girls lived with their captors for a year, then were traded to the Mohave, who raised them. Mary Ann died, and Olive was ransomed back to the whites in 1856, wearing a chin tattoo. She became a celebrity in her day, embarking on a lecture tour promoting a book that Rev. Royal B. Stratton wrote about her ordeal, The Captivity of the Oatman Girls. Newly published, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman is the first scholarly biography of Olive Oatman. It debunks a number of myths that have circulated about her over the past century and a half. Ten such myths follow.

1 – Her captors were Apaches.

Though Olive later identified them as Apaches—commonly assumed, in her era, to encompass a variety of dangerous Southwest tribes—her captors were probably much less notorious. Their proximity to the murder site, regular contact with the Mohave Indians, hunter-gatherer lifestyle and small scale farming practices suggest they were one of four fluid groups of Yavapais. Most likely they were Tolkepayas, a name that distinguishes them more geographically than culturally from other free-ranging yet interconnected Yavapais.

2 – The rest of the Oatman family was killed in the massacre.

Not everyone. Olive’s brother Lorenzo, nearly 15, was left for dead near Gila Bend. He managed to return to the remainder of the party the Oatmans had left behind at Maricopa Wells. He and Olive reconnected at Fort Yuma soon after her ransom.

3 – She was a slave to the Mohave.

Though she and her younger sister Mary Ann did serve as slaves to the Yavapais during the year they spent with them, they were not slaves to the Mohave. They were adopted into the family that had arranged for their retrieval from the Yavapais, given their clan name Oach and treated as family. The term the Mohave used to describe them, “ahwe,” meant “stranger” or “enemy,” not “slave” or “captive.”

4 – She wore a tattoo that marked her as a captive.

In her public lectures, Olive said the Mohave tattooed their captives to ensure they would be recognized if they escaped. “You perceive I have the mark indelibly placed upon my chin,” she said, neglecting to mention that most Mohave women wore chin tattoos. Stratton’s book, too, claimed that the girls received designs specific to “their own captives.” But the very pattern Olive wore appears on a ceramic figurine of the late 19th-early 20th century that displays traditional Mohave face painting, tattoo, beads and clothing.

5 – Her Mohave nickname was Olivia.

The Mohave called her “Aliutman,” an elision of Olive Oatman. But the tribe loved teasing and obscene nicknames. Olive’s name, Spantsa, the meaning of which is not printable here (it’s explained in the biography), appeared on the travel pass that was sent by the U.S. army to the Mohave for her ransom. Stratton listed her name as “Olivia” when he quoted the pass in The Captivity of the Oatman Girls, presumably after learning of the nickname’s explicit meaning.

6 – She wanted to leave the Mohave but had no opportunity for escape.

Olive told one of the first reporters to interview her that the Mohaves always told her she was free to leave when she wanted to, but that they wouldn’t accompany her to the nearest white settlement for fear of retribution for having kept her for so long. Since she didn’t know the way, she reasoned, she couldn’t go. But that didn’t explain why she didn’t approach any of the 200 white men who mingled and traded with the Mohave for a week in 1854 when the Whipple Expedition came surveying for a railroad route—a major event during her life as a Mohave that was conspicuously omitted from Captivity of the Oatman Girls.

7 – She married a Mohave and had Mohave children.

Olive almost certainly didn’t marry a Mohave or bear his children. If she had, it would have been a highly unusual, thus memorable, piece of tribal history. The late Llewellyn Barrackman, who was the tribe’s unofficial historian, reported that if Olive had, “we would all know.” He added that the children would have stood out as mixed-race Mohaves who could have been easily traced to her. Furthermore, though she married after her ransom, Olive never had biological children, which raises the possibility that she couldn’t. Finally, a half century after her ransom, when the anthropologist A.L. Kroeber interviewed a Mohave named Musk Melon who had known Olive well, he said nothing about her having been married.

8 – She hated the Mohave Indians.

Olive cried into her hands when she was delivered to the U.S. Army at Fort Yuma. She paced the floor and wept at night after she and Lorenzo moved to Oregon to live near their cousins. A friend described her as a “grieving, unsatisfied woman” who longed to return to the Mohave. And when Olive heard that a tribal dignitary named Irataba was traveling to New York in 1864, she went to visit him. As hard as Stratton tried to twist her story into an indictment of the “degraded bipeds” who raised her, Olive’s love for the Mohave bleeds through the pages of Stratton’s book, and it is also clear in the interviews she gave soon after her ransom.

9 – She lived happily after her ransom.

She married a rancher who became a wealthy banker, and they adopted a child and lived a comfortable life in Sherman, Texas. But in her forties, Olive battled debilitating headaches and depression. In 1881, she spent nearly three months at a medical spa in Canada, largely in bed. Oatman seemed to suffer from some chronic form of post-traumatic stress for most of her later life.

10 – She died in an insane asylum.

Olive died of a heart attack in 1903; she was never in an asylum. It was, ironically, Stratton who was committed to an asylum and died there in 1875.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy University of Nebraska Press –

https://truewestmagazine.com/heart-gone-wild/