The cause was a horse race in Placerville, California, on June 15, 1864. Sporting man Bill Davis fixed the contest—his horse, the favorite, lost. He won $4,500 off the other entrant. Four gamblers—called Dutch Abe, Spanish Bob, Ball and Hank Stevens—lost big bucks on the race and came gunnin’ for Davis.

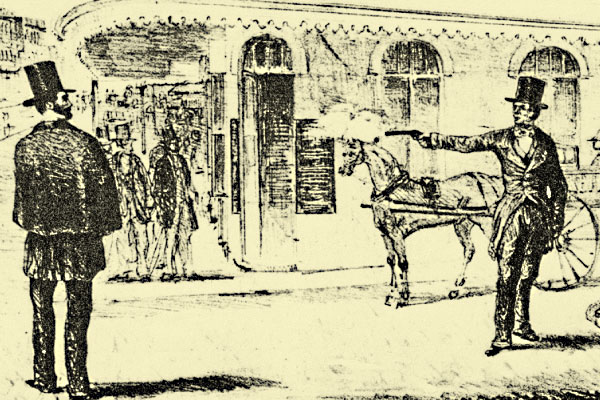

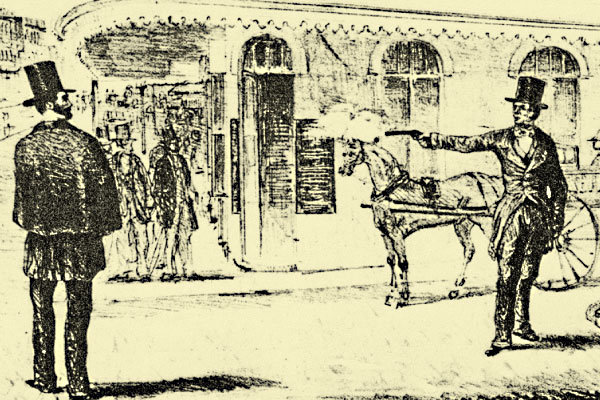

They found him six days later, on Montgomery Street, in San Francisco. Davis was getting his boots shined when Ball and Dutch Abe opened up on him with pistols. According to an account by a correspondent from the New Orleans-based Picayune, Davis returned fire, killing Ball. He chased Dutch Abe onto the sidewalk, saying, “You’ve made a mistake,” as he put a bullet in the man’s chest. Dutch Abe died two days later.

Davis, wounded in the left arm and the right cheek, took the gun from Ball’s hand, went down the street to the Fashion—which isn’t identified, but was probably a saloon—and called out for the other two gamblers to meet him outside.

When Hank Stevens and Spanish Bob exited, Davis put two bullets into Stevens, leaving him mortally wounded on the sidewalk. Davis and Spanish Bob traded shots; each was hit several times until they were out of ammunition. The two pulled derringers and began crawling toward each other until they were about five feet distant. Each fired. Spanish Bob died on the spot, with Davis proclaiming, “He’s gone, I cooked him.”

Davis, hit six times, was expected to survive. The newspaper reported Davis had laughed through the entire affray.

It’s a great story. Which is all it is.

At the time, none of the San Francisco newspapers carried accounts of the gunfight, which would have merited front page coverage. The many newspapers that did publish it (mostly in the East and Europe, in addition to New Orleans) all printed the story, word for word, from the unnamed Picayune reporter.

On October 7, San Francisco’s Daily Alta California finally published the story—but with a decidedly sarcastic tone. Six weeks later, on November 22, the paper went further: “The whole story was a humbug, gotten up by a well known sensational Bohemian, of the meanest class, in this city, and was understood here, but the effect abroad was different.”

The “well known sensational Bohemian” was never identified, at least in print. But the paper expressed concern that such stories hurt the reputation of San Francisco, making the city sound more violent than it already was.

A California gambler named Bill Davis did organize a horse race, in April 1864, the Daily Alta California reported. But it was not a rigged race nor did it trigger a face off between sporting men.

That’s how legends are made; the print era offers myths to debunk just like the Internet age does today.