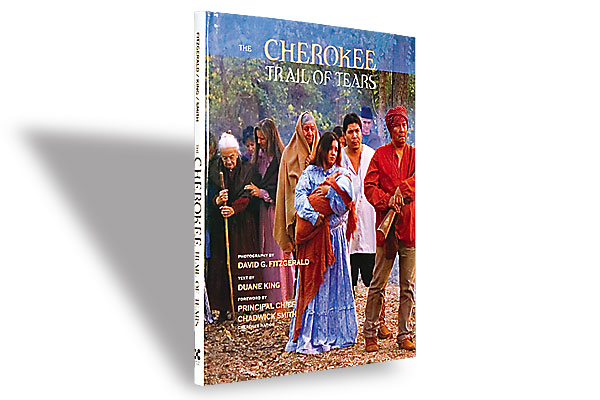

Come off it. Everybody gives credit to Dee Brown for changing the way white Americans think about American Indians.

Come off it. Everybody gives credit to Dee Brown for changing the way white Americans think about American Indians.

Hey, I love Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee today as much as I loved it when I first picked it up in college—and that worn-out 1981 Pocket Books paperback still sits proudly on my bookshelves—but give me a break. The real heroes of the pro-Indian movement started the cause six years earlier.

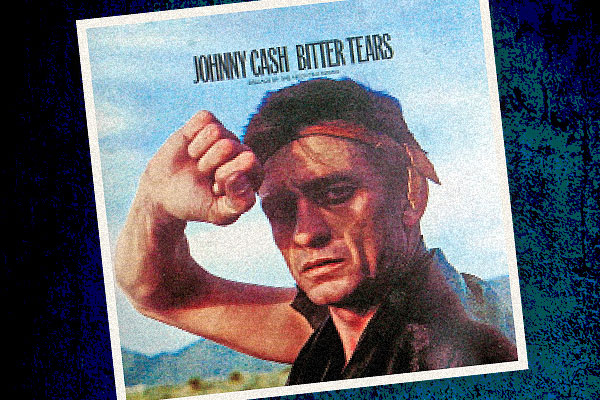

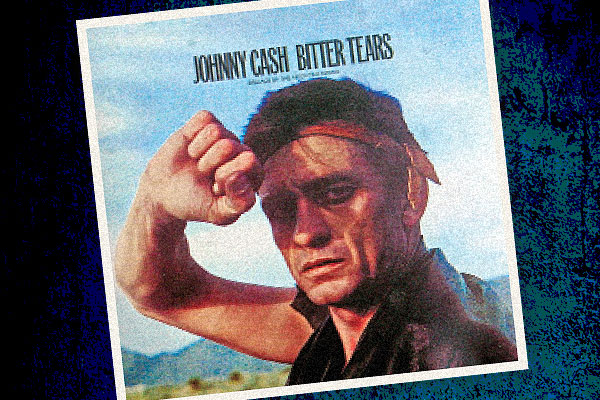

Today—50 years later—let us give proper respect to Thomas Berger and Johnny Cash. I’m betting that in 1964, six years before his seminal work was published, Brown was sitting in his study reading Little Big Man and listening to Bitter Tears.

Berger’s Little Big Man has earned the author comparisons to Mark Twain. What’s not to love about the adventures of Jack Crabb, a white boy who grew up among the Cheyennes and survived Custer’s “Last Stand?”

The anti-establishment movie version that followed in 1970 served as an indictment of the Vietnam War. As much as I enjoy the performances of Jeff Corey as Wild Bill Hickok and Richard Mulligan as an insane George Custer, the film loses focus because of the silly attempts at 1970s comedy.

Berger’s novel maintains its vision. It is funny, yet touching, and it treated Indians as human beings, not stereotypes to fit into clichéd plot devices. Often, the book has made me laugh out loud.

On the other hand, you won’t find much to laugh at while listening to Cash’s Columbia Records album Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian.

“With victories he was swimming / He killed children, dogs and women,” Cash sings of Custer. Those words came from songwriter Peter La Farge, who claimed to be of Indian descent and was the son (Peter said he was adopted) of Pulitzer Prize winner Oliver La Farge.

Peter wrote several songs Cash recorded on the album, including “The Ballad of Ira Hayes”—about the Pima Indian who helped raise the U.S. Marines flag at Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945, and died a drunk roughly 10 years later. The songwriter himself would be dead, probably from an overdose, in 1965.

Think about it. You’re Cash in 1964. You’re hooked on drugs. Your life and finances are in the toilet. So you release a concept album in which the Indians are the good guys and the white guys are evil. And you want that to be played on white Country stations.

Now that takes guts.

Granted, Brown had guts to write a masterpiece that The Washington Post would declare “conveys not how the West was won, but how it was lost.”

But, honestly, would Brown have written that book if he hadn’t first heard Cash singing the following words? “Ghosts of broken hearts and laws are here/ And who saw / the young squaw/ They judged by their whiskey law/ Tortured ’til she died/ of pain and fear/ Where the soldiers lay her back/ Are the black Apache tears.”

Could Brown have written such prose if he had not read Berger’s reasoning for why Custer wasn’t scalped? In Little Big Man, when Crabb tells his Cheyenne grandfather that Custer wasn’t scalped because “The Indians respected him as a great chief,” Old Lodge Skins corrects him: “They did not scalp him because he was getting bald.”

Johnny D. Boggs’s favorite exchange in Little Big Man: Jack Crabb: “What are you so nervous about?” Wild Bill Hickok: “Getting killed.”