True West asked me to track down Bigfoot.

True West asked me to track down Bigfoot.

Huh?

You mean the giant, hairy beast that they do the television documentaries about? What’s next—ancient aliens? (Oops. That’s the History Channel’s area of expertise).

But no, my editor is talking about a different kind of legend, one who strode across 19th-century Texas and left some big shoes to fill (so to speak). A man named Wallace, a rough and tough frontiersman whose exploits have been told for 140 years or so.

Unfortunately, Bigfoot Wallace is just about as mysterious as the sasquatch—lots of stories, but not a lot of hard evidence. He’s had three biographies written about him, but Wallace was the main source for the first one in 1870. While he wasn’t necessarily a liar, the man was known to embellish the retellings of his own exploits. The second biography, published in 1899, was based on more talks with Wallace, and the stories didn’t always match up with the ones in the first book. The third biography, which came out more than 70 years ago, was based on the first two.

His life story has lots of gaps, which is too bad, because Wallace was a giant of a man who accomplished great deeds and was involved in amazing events. His story doesn’t need any varnish.

But until the truth is uncovered, we will have to deal with the story as it has been told by these three biographers and others. This is what we know about the man called Bigfoot.

William Alexander Anderson Wallace was born in Lexington, Virginia, on April 3, 1817. Family lore said he was a descendant of another William Wallace—the Scottish warrior known as Braveheart (this family really liked nicknames). Little is known of our Wallace’s formative years, but he headed to Texas in November 1837.

Wallace said he went to Texas to avenge the deaths of family members who had died in the Goliad Massacre, when Mexican forces slaughtered more than 300 surrendered Texans on March 27, 1836. Some accounts state Wallace lost a brother and cousin; others aren’t so sure. He got to Texas too late for the Texas Revolution. Many years later he told biographer John C. Duval that his account with the Mexicans had been squared.

The young man must have cut an impressive figure—he was said to be about six foot, two inches tall and 240 pounds of muscle. In that era, Wallace was a giant, which may have helped him gain the nickname of “Bigfoot” (see “The Origin of Bigfoot”).

Once Wallace got to Texas, though, he was less than impressed. “Such a sight I never saw…. I would rather see a sister of mine in the grave than in Texas,” he wrote in his first letter back home.

He must have gotten more comfortable with the place. He would spend almost his entire remaining 62 years there.

Wallace settled in the Hill Country, mostly around San Antonio and Austin. When he had first arrived in Texas, he wandered, with his wife and three boys, living off the land and learning the finer points of being a frontiersman. While hunting alone, he was captured by Lipan Indians, who planned to kill him. Wallace later said that an old Indian woman adopted him at the last moment, sparing his life. Wallace eventually escaped (one account states he was a captive for three months, while another puts it at a week or so).

Over the next few years, Wallace tried a number of different jobs—farming, hauling rocks and logs, construction. Sometime in the 1840s, he joined up with Texas Ranger Capt. John Coffee “Jack” Hays to fight Indians and outlaws, some of whom were summarily executed, no matter what their crime. The record is not clear as to whether Wallace became an official Ranger in 1840, as the second biography states, or a few years later, as Duval wrote in his Wallace biography.

In 1842, Wallace got his shot at Mexicans when their army invaded Texas, getting as far as San Antonio. He participated in two battles that sent the troops of Antonio López de Santa Anna scurrying south. The Texans followed them into Mexico, a decision that would come back to haunt Wallace. On Christmas Day, he and other troops and Rangers attacked the town of Mier in northern Mexico—only to find that they were outnumbered 10 to one. The Texans surrendered and were held captive in various cities for nearly two years. Conditions were terrible, and many of the captives died from wounds, disease or starvation.

The men tried a mass escape in February 1843, but 176 of them were recaptured, including Wallace. Originally, all were sentenced to death, but the order was modified—one man in 10 would die. A lottery was held to decide who lived and who died. One hundred seventy-six beans were put in a jar; 17 of them were black. Those who drew out the black beans were shot. Wallace “dug deep” and got a white bean. On August 25, 1844, he and four others were released and sent back to Texas; by September, the rest of the prisoners were set free.

Not long after he got back, Wallace joined the Rangers in combating Indians and criminals. The Rangers became soldiers in 1846 during the Mexican War; Wallace rose to lieutenant before the fighting was done. In 1850, he contracted to carry the mail between San Antonio and El Paso, a distance of around 1,100 miles.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Wallace opposed Texas secession. But he couldn’t fight against his own people, so he guarded the frontier against Indian attacks. After the war, he settled in Frio County, southwest of San Antonio, spending most of his time hunting and telling stories of his exploits. In 1883, a nearby town was renamed Bigfoot in his honor.

As the years went by, and his body weakened, Wallace stayed close to home, where he lived alone, his wife and sons having been murdered by Indians soon after the family had moved to Texas. He died on January 7, 1899. The Texas Legislature put up money to move his body to the state cemetery in Austin. A museum dedicated to him was opened in Bigfoot in 1954, and it is still the town’s claim to fame.

Bigfoot Wallace remains a giant figure in Texas history, but he’s still waiting for a historian to dig deep and determine the truth versus the legend.

As for me, I’m awaiting a call from True West about those ancient aliens.

THE ORIGIN OF BIGFOOT

So just where did William A.A. Wallace get his nickname?

His friend and biographer John C. Duval wrote that Wallace got the handle after fighting an oversized Waco Indian called Big Foot.

Biographer Andrew Jackson Sowell’s version of that story is that, in 1839, Wallace was accused of some theft that was actually committed by that Indian. The frontiersman proved his innocence by placing his moccasined foot inside the much larger footprint of the real culprit. One of Wallace’s friends started calling him Bigfoot as a joke. According to that story, that same friend was later killed by the Waco Big Foot.

Or maybe he just had big feet.

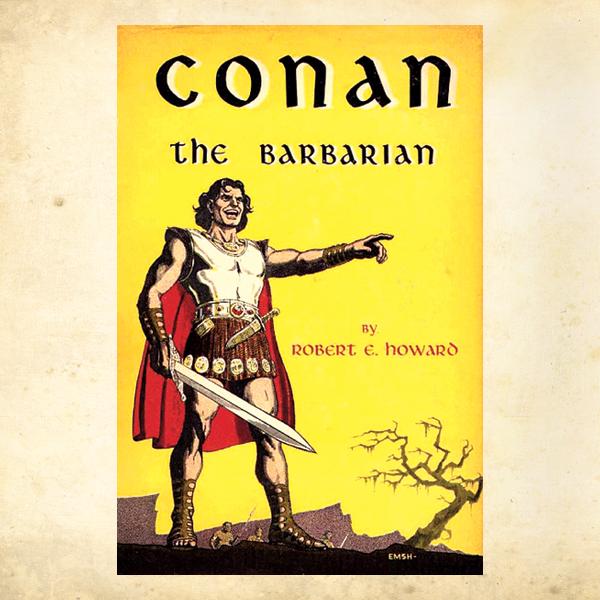

BIGFOOT AND CONAN THE BARBARIAN

One of Bigfoot Wallace’s biggest fans was Texas fantasy writer Robert E. Howard, who is best known for his tales of Conan the Barbarian.

Back in the 1930s, Howard kept up a correspondence with author H.P. Lovecraft, and it’s surprising how often the subject of Wallace came up.

“He [Bigfoot Wallace] is perhaps the greatest figure in Southwestern legendry,” Howard told Lovecraft. “Hundreds of tales—a regular myth-cycle—have grown up around him. But his life needs no myths to ring with breath-taking adventure and heroism.”

Some of Howard’s letters recounted those tales in stylized language his readers would recognize.

More than one Howard chronicler has theorized that Wallace was a model for Conan the Barbarian—huge physically and a rough and tough adventurer with a personal code of honor.

TEXAS JOHN—THE FIRST TEXAS MAN OF LETTERS

Bigfoot Wallace’s first biographer was just about as colorful as the man himself.

John C. Duval—later known as Texas John—came to Texas from Kentucky in 1835 and got involved in the Revolution. He was one of the few survivors of the Goliad Massacre (his brother died there) on Palm Sunday, 1836.

After studying engineering at the University of Virginia, Duval returned to Texas and joined the Texas Ranger company led by John Coffee Hays—which included Bigfoot Wallace. The two became friends and spent many hours swapping stories.

After serving the Confederacy in the Civil War, Duval turned to writing—mostly about the early days in Texas, including his Goliad escape. Then he penned the story of his pal, The Adventures of Bigfoot Wallace, the Texas Ranger and Hunter, which was published in 1870. The book was (and is) the primary source for all future Wallace biographies.

Historian J. Frank Dobie said that Duval’s writings provide an important view of early Texas and qualified the author as the “First Texas Man of Letters.” But Dobie added a caveat—Duval helped Wallace “stretch the blanket” a bit, so readers had to take his stories with a grain of salt.

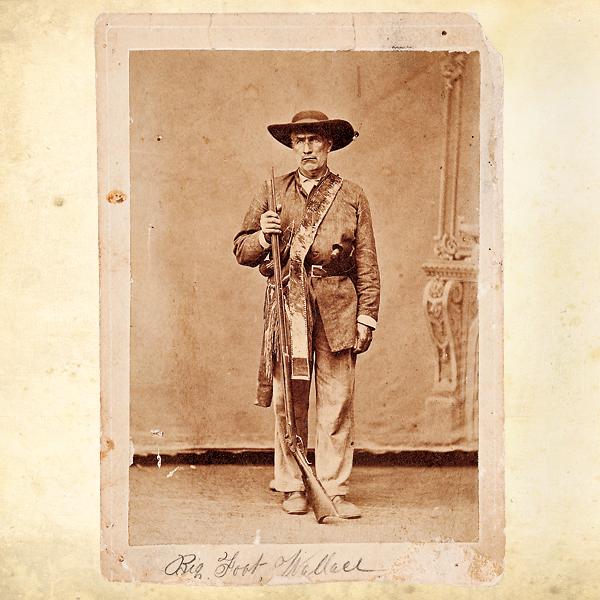

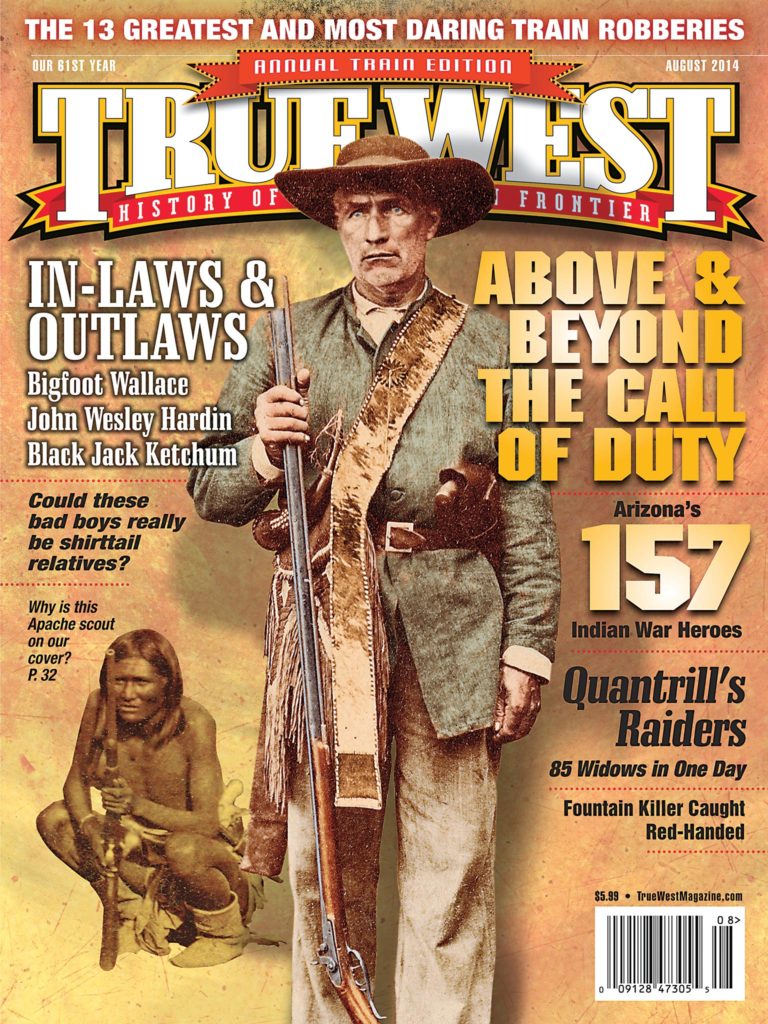

Photo Gallery

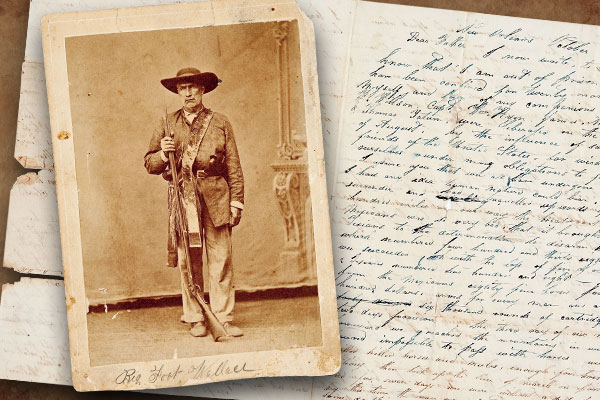

On the back of this 1872 albumen photo of William Wallace, a note states the hunting pouch Wallace is wearing was “taken from the Indian Chief ‘Big Foot’ from whoom [sic] he derived his name.” The photo sold for a $10,000 bid at Heritage Auctions in 2013.

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions –

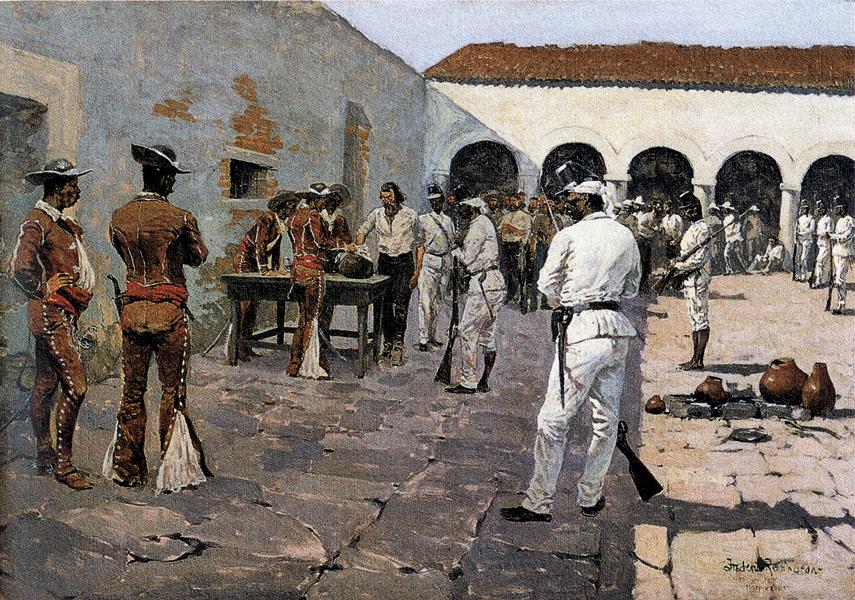

Frederic Remington painted the Black Bean Lottery that condemned 17 of 176 Texas prisoners to death in 1843 after being captured by Mexicans during the ill-fated Mier expedition. After Wallace was released in 1844, he wrote his father, “…my bad treatment while in Mexico compells [sic] me to return, for i am determined to fight the Mexicans so long as i live in Texas.”

– Courtesy Hogg Brothers Collection, Gift of Miss Ima Hogg, Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas –

Ed Emshwiller’s cover art for Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, published by Gnome Press in 1954, portrays a physically huge hero who some believe may be based on Bigfoot Wallace.

– Courtesy Grove Press –

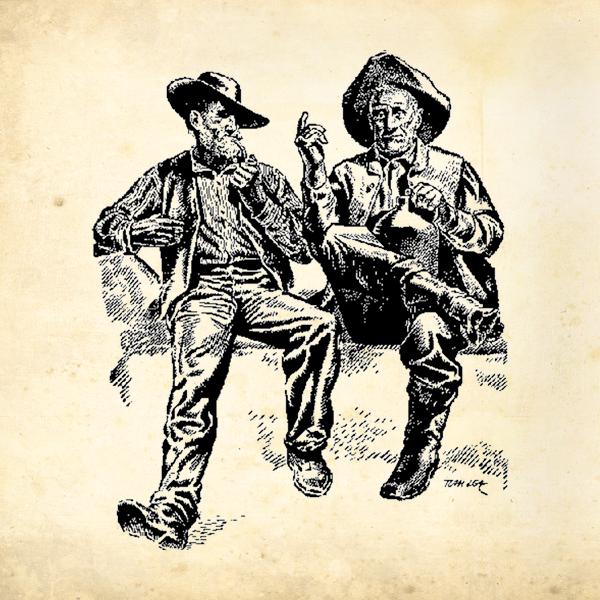

Tom Lea illustrated Bigfoot Wallace with John C. Duval for J. Frank Dobie’s book John C Duval: First Texas Man of Letters.

– illustrated By Tom Lea –

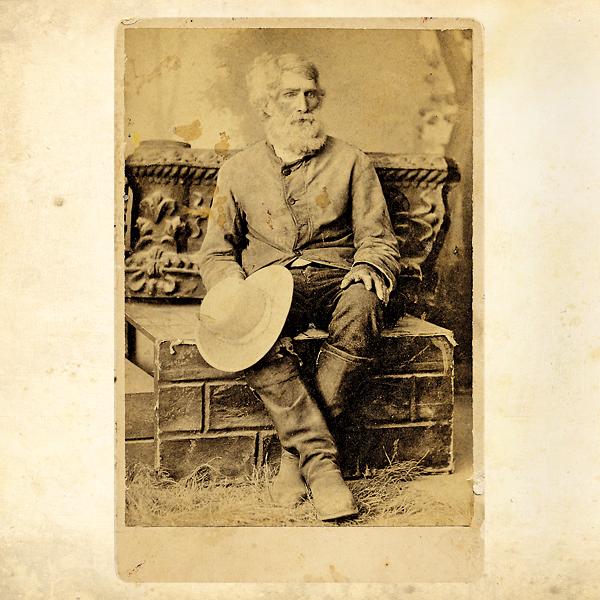

This 1880s photograph of William “Bigfoot” Wallace is owned by the Witte Museum in San Antonio, Texas.

– Courtesy Witte Museum –