About 1980, a planchet was discovered near the Arizona community of Wheatfields, just a few miles north of Miami, about 40 miles east of the old San Carlos reservation.

About 1980, a planchet was discovered near the Arizona community of Wheatfields, just a few miles north of Miami, about 40 miles east of the old San Carlos reservation.

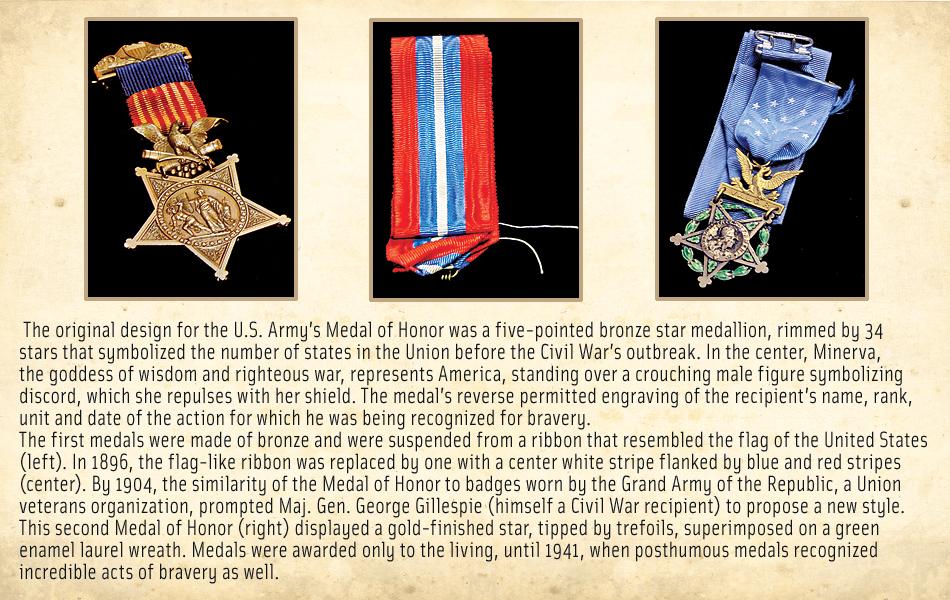

Upon further inspection of the metal portion of the decoration, one could see it was a Medal of Honor. This priceless medal was lying in the midst of a few flat rocks, forming a square and covered by a bit of earth. Who placed it there, and why did that person do so? We may never know, just as we may never resolve the intriguing story of the man who earned it: Chiquito.

Roughly a decade before Chiquito earned his medal during the 1872-73 campaign in the Tonto Basin, the Arizona Territory became the initial link to the nation’s highest decoration for valor. Although the American Civil War gave birth to the Medal of Honor, the earliest action revered with the medal was a fire fight in what became Arizona Territory. The soldier who received it was an unlikely martial hero.

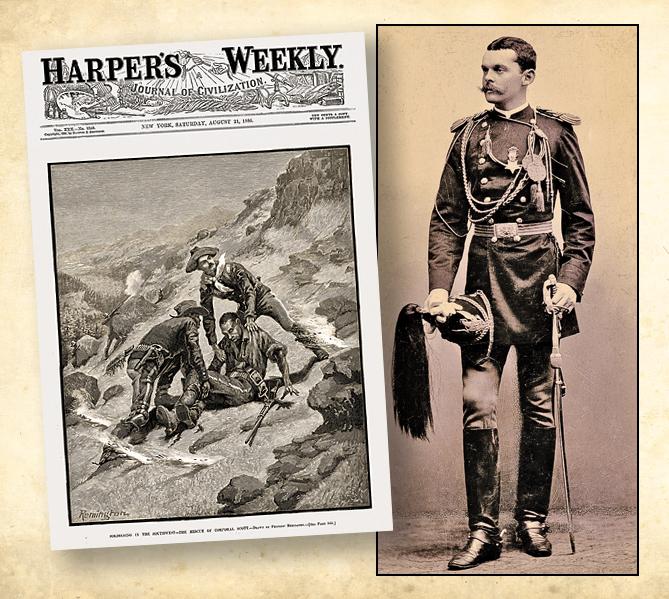

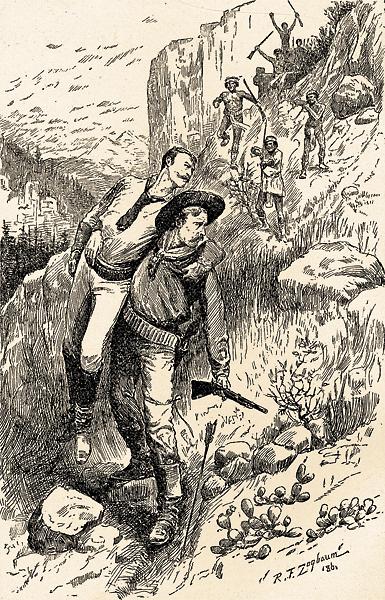

Bernard John Irwin received his MD at New York Medical College. Soon after graduation, he signed on as a military surgeon. By early 1861, he had been practicing for four years in the Southwest, when word came that troops near Apache Pass were surrounded by Indians. With only 14 men, Irwin led a rescue party eastward from Fort Buchanan to link up with besieged troops under Lt. George Bascom.

The doctor-turned-combat leader and his command engaged in a fierce fight against Cochise and his warriors. In danger of being overrun, Irwin’s column reached Bascom’s anxious force in early February. The attack broke off. Decades later, Irwin was presented the Medal of Honor for his daring actions on February 13-14, 1861, the earliest engagement that resulted in the bestowal of this prestigious symbol of courage.

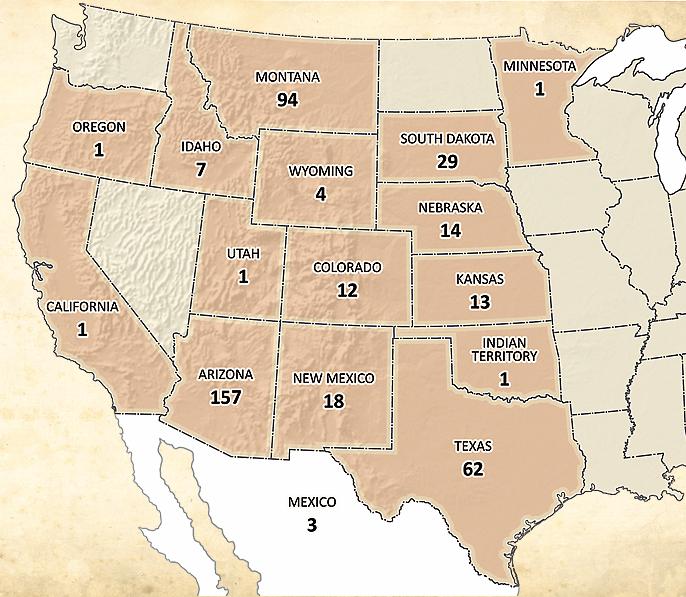

During the three decades that followed Irwin’s daring rescue, another 156 men would follow in the doctor’s footsteps, displaying extraordinary courage under fire in volatile Arizona. This number accounts for nearly one-half of all the 419 Medal of Honor recipients in the states and territories west of the Mississippi River.

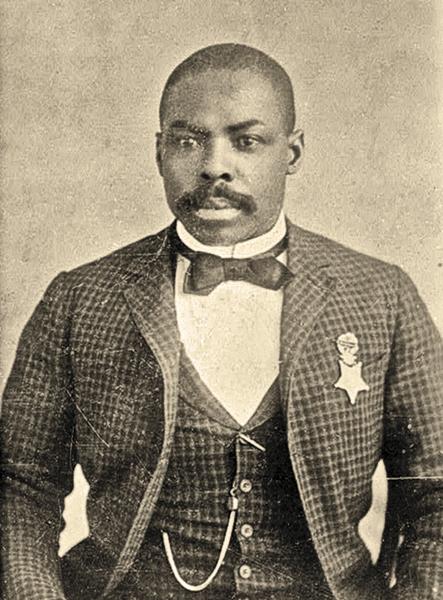

Who were these men who performed so valiantly, often with disregard for their own safety? Military records indicate that the recipients came from a variety of backgrounds and diverse origins, ranging from newcomers from Ireland and other parts of Europe to 11 American Indian scouts who were born in Arizona as members of a people who came to be known as the Apaches. Some of these bravest of the brave achieved prominence; others died in obscurity.

One of those whose name would live on in the Arizona annals served with distinction during 1881, when an Apache holy man and prophet named Noch-ay-del-klinne preached the resurrection of dead warriors and leaders who would restore the ancestral lands of his people. His message eventually triggered a revival that ended in bloodshed, including his death at the hands of troops from the 6th U.S. Cavalry who took him into custody.

As part of the outbreak, a large party of the prophet’s followers surrounded Fort Apache. Private First Class Will C. Barnes of the Signal Corps, at great risk to his life, scaled the heights adjacent to Fort Apache to send the message for help to lift the siege. After his military service, Barnes remained in the territory. Among his contributions to his adopted home, Barnes wrote an important reference work titled Arizona Place Names.

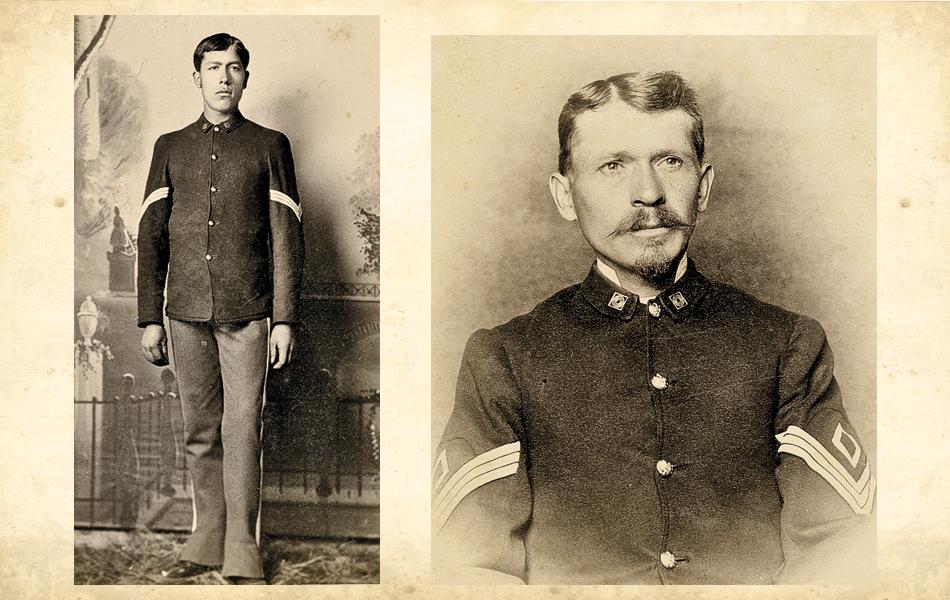

Another future author, Lt. Charles King, would emerge as a result of a daring deed. But in King’s case, he was the beneficiary of a heroic act in the heat of battle, rather than the performer of a gallant exploit. His hero was 30-year-old, St. Louis, Missouri-born Bernard Taylor, a sergeant in the 5th U.S. Cavalry. One of Taylor’s superiors described the sergeant as an “admirable specimen of the Irish-American soldier” and a “daring, resolute, intelligent man, and a non-commissioned officer of high merit.”

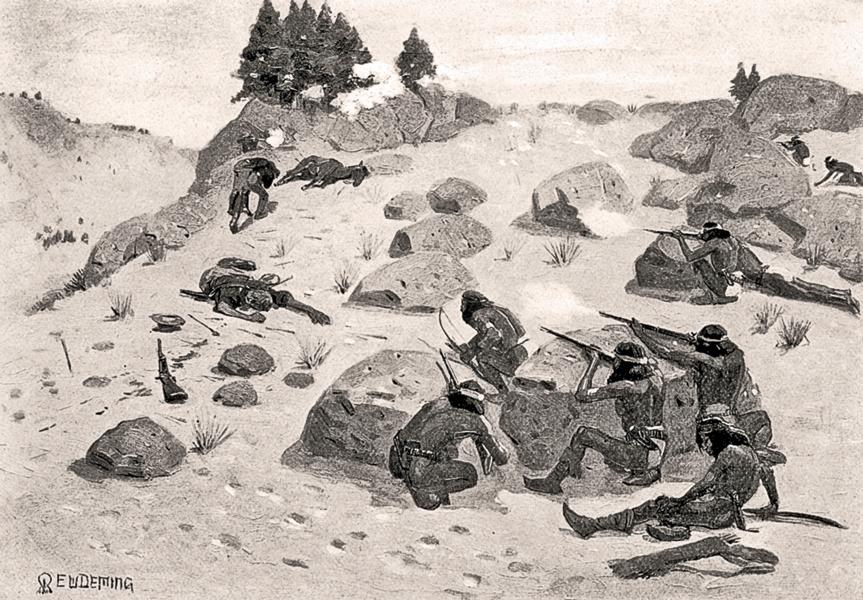

On November 1, 1874, Taylor set out from Camp Verde, Arizona, with a detachment commanded by King, in pursuit of Apaches. After making camp at Sunset Pass, the party, including a contingent of Yavapai scouts, made for high ground in order to survey the area. As King’s men climbed the mesa, Apaches opened fire from ambush and struck the lieutenant in the head and eye. Eventually, another shot shattered his arm. Taylor came to the semi-conscious King’s aid, and while under heavy fire, carried him a half mile back to safety. King survived.

On April 12, 1875, Taylor was presented the Medal of Honor for his selfless action. Two days later, Taylor died of a lung disease. He was buried in the national cemetery at the Presidio of San Francisco in California.

Other enlisted men rose to the occasion, including 11 Apaches. For these Indians, enlisting provided a means to defeat their traditional enemies, continue their warrior traditions, remain on their ancestral lands, provide for themselves and their families, escape the confinement of reservation life, gain status among their people and afford a slightly better way of life than the precarious rations issued by the government. In so doing, they attempted to live within two worlds—that of the white man and that of the traditional ways of their ancestors. Whatever their reasons for joining the military, these scouts were a distinguished band of brothers.

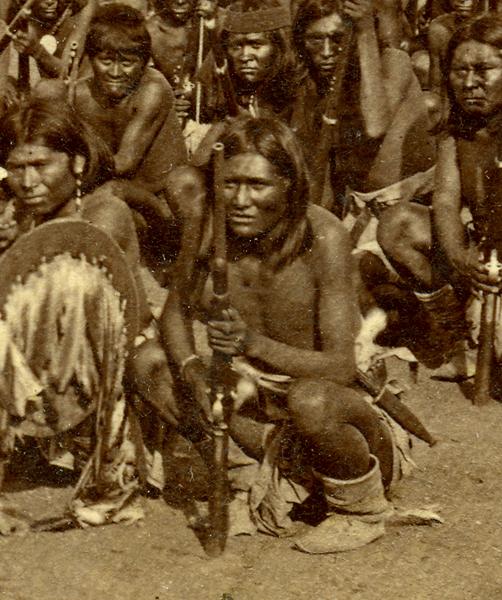

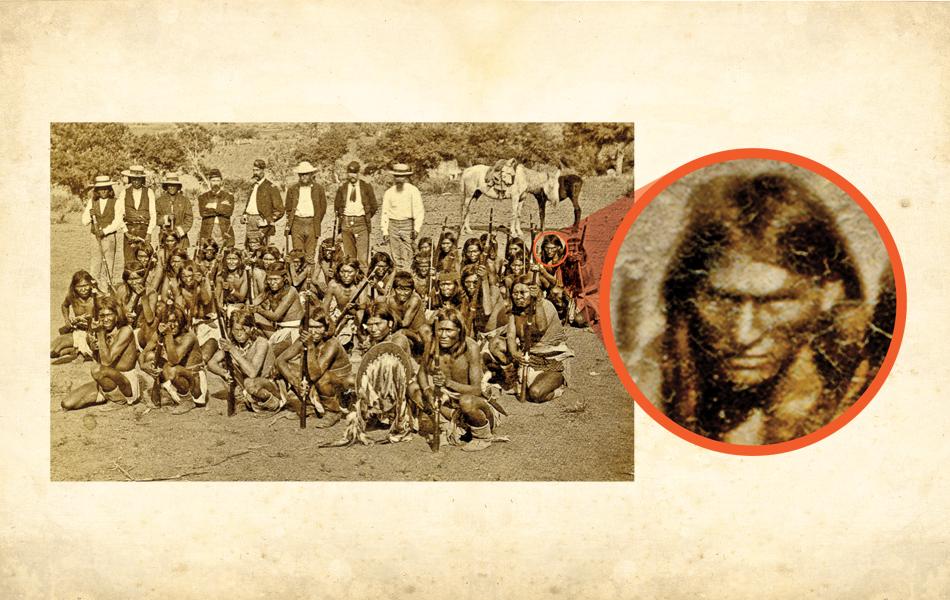

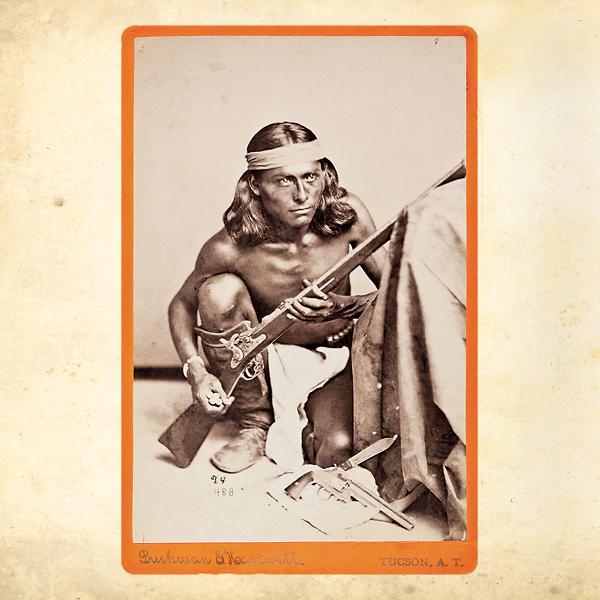

Which brings us to Chiquito. Surviving official military records tell us little about Chiquito, one of the Apache scouts from Company A who received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the Tonto Basin campaign. What is certain is that the name Chiquito appears on government rolls in reference to many scouts and other Indian males. But the man who was singled out for the Medal of Honor enlisted under Lt. Col. George Crook in 1872, under identification number 204. He was from a part of the Apache people called the Sierra Blanca, or White Mountains, by the U.S. Army. Evidently, he deserted, at least temporarily, after the Tonto Basin operations. We do not know the name by which his family called him. What happened to him after being singled out for his heroic service is also unknown.

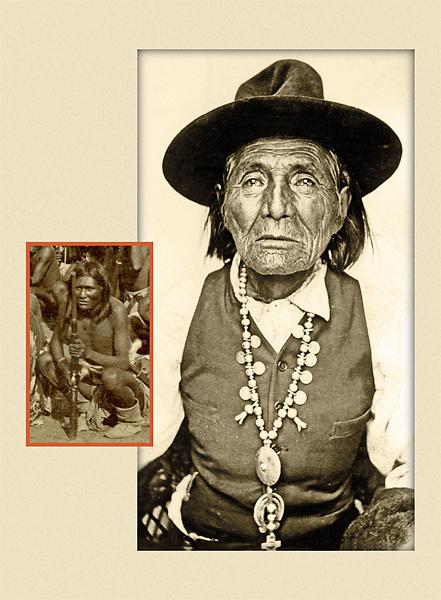

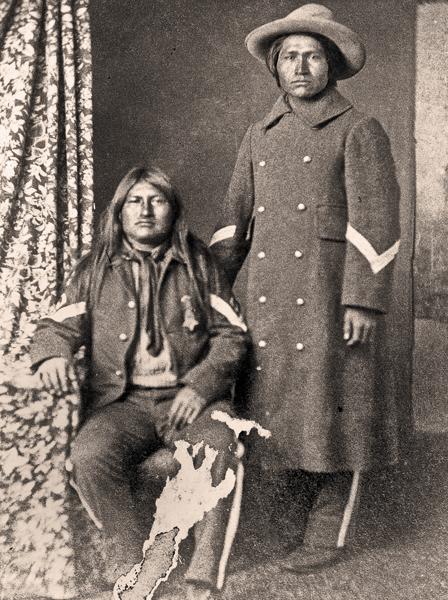

Conversely, we know a great deal more about Chiquito’s fellow warrior scout, Alchesay, who joined the army probably while in his late teens. He, too, was one of the scouts recruited for the Tonto Basin campaign by Arizona Departmental Commander Crook, and for which he earned his Medal of Honor. Alchesay rose to the rank of sergeant, serving many tours of duty before becoming a headman among his so-called White Mountain Apache people. He twice visited the White House and staunchly championed education, stating he wished his young people to “learn the ways of the white people but to stay true to the ways of the Indian.” Bridging the old and new was a lifelong focus for the brave, wise, tireless and resilient leader in peace and war. He died on August 6, 1928, at the age of 73.

These few stories provide only a glimpse into the deeds of valor acted out on the hard fought stage of old Arizona. More of this compelling story unfolds in a new exhibit that premiered at the Arizona Historical Society Museum in Tempe this May and is open through October before it travels the state over the next three years. Some of these heroes became famous, but for most, their life stories have been lost in the midst of time, just as what prompted them to act so courageously under fire never will be known.

John Langellier is the director of Arizona Historical Society’s central division at Papago Park in Tempe. See AZMOH.org for more on the exhibit. He previously served as director of Sharlot Hall Museum in Prescott.

Photo Gallery

Cavalry Capt. John Bourke described the warrior Alchesay (inset) as a “perfect Adonis in figure, a mass of muscle and sinew, of wonderful courage, great sagacity, and as faithful as an Irish hound.” He is pictured at right, in older age, still strong, still strking. Alchesay High School in Whiteriver, Arizona is named for him.

– Photographs courtesy Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, VintagePhoto.com –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions –

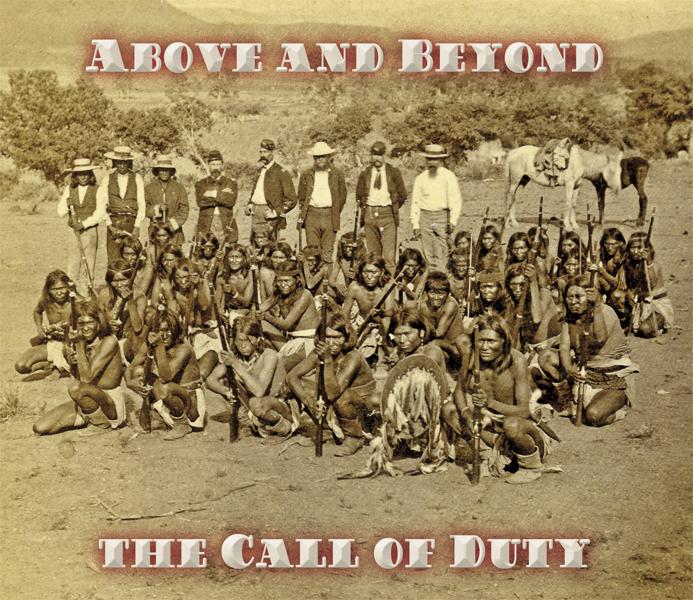

After the 1872-73 Tonto Basin Campaign, George Crook posed with some of his key aides and scouts, including Chiquito and nine of the Apaches who earned the Medal of Honor for their actions during the intense fighting that took place during this series of engagements. Unfortunately few of these courageous fighters were identified except the men in the front and back rows.

– Courtesy Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, VintagePhoto.com –

– Courtesy Arizona Science Center –

– Courtesy Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, VintagePhoto.com –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions –

– True West Archives –

– Harper’s Weekly / Clarke photo courtesy Heritage Auctions –

– Courtesy John Langellier –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –