“Everybody complains about the weather, but nobody does anything about it,” Mark Twain once said.

“Everybody complains about the weather, but nobody does anything about it,” Mark Twain once said.

Obviously, Samuel Langhorne Clemens never met Robert G. Dyrenforth.

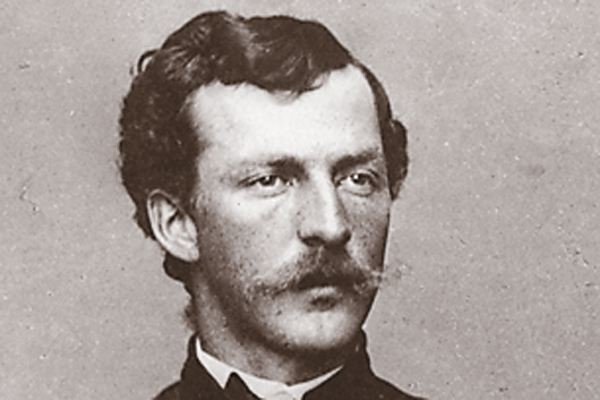

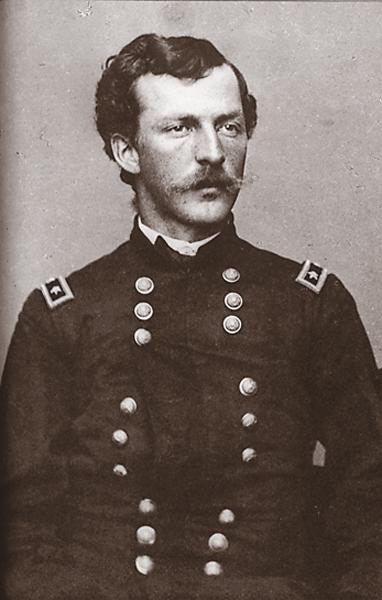

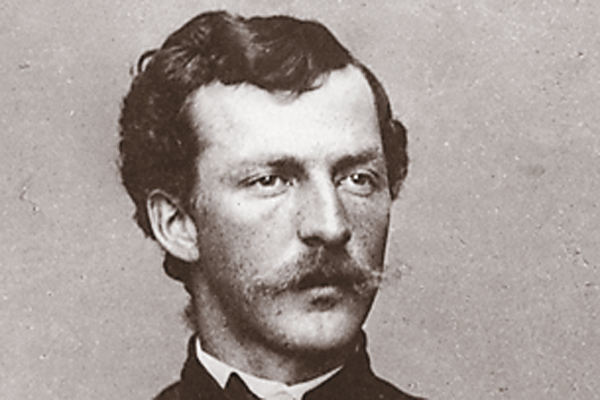

A U.S. Department of Agriculture special agent, Dyrenforth had been educated at the University of Heidelberg in Germany and Columbian University (now George Washington University) in Washington, D.C. During the Civil War, he served in the Union Army, learning how to work with explosives, and was wounded twice. Dyrenforth also worked as a war correspondent during the Austro-Prussian War (the Seven Weeks War of 1866), was a patent attorney and also an assistant commissioner for the patent office in D.C.

What fascinated Dyrenforth, however, was rain—or rather, the lack of it—and some interesting theories about War and the Weather. That was the title of an 1871 book by Edward Powers, documenting how, even in dry regions, “copious” rain fell after battles during which there had been cannon fire. Brigadier Gen. Daniel Ruggles of Virginia had conducted similar experiments in 1880, setting off explosions in the air.

One theory claimed that the bombs jarred the air and reacted from the smoke, which caused the rain. Or it could be that the explosions produced electricity and friction, or the atmospheric pressure reacted somehow to the “air-quakes” or the gases and heat did something….

Whatever the cause, Dyrenforth thought it was worth investigating. Illinois Sen. Charles B. Farwell agreed, and with the backing of the U.S. Government, Dyrenforth began his scientific rainmaking experiment in 1891.

The “Great Die”

After obtaining balloons, bombs and other equipment, Dyrenforth and his crew began sending explosive-filled balloons into the atmosphere, which they detonated near Washington, D.C.

Instead of producing a thunderstorm, the experiment resulted in at least one noisy complaint. “I have a herd of very fine Jersey cows, some with calf, and the tremendous explosion yesterday right over my barn was calculated to cause abortion,” wrote William J. Rhees, chief clerk at the Smithsonian, on June 23. “I have had this happen from a thunder storm and your bomb was worse than any thunder. It shook the house and alarmed my family. Please, Mr. Secretary, move your dynamiters away from ‘Oakmont,’ Piney Branch.”

Out in drought-stricken Texas, however, ranchers could tolerate the cannonades. So when Nelson Morris invited Dyrenforth to his C Ranch near Midland—agreeing to pick up local expenses—the government team took its balloons and bombs west, arriving at the ranch on August 5.

Western ranchers and farmers were no strangers to rain-producing experiments. Fields had been plowed (they held moisture, thus increasing evaporation and causing rain). Prairies had been burned (the heat and smoke caused precipitation). Chimneys had been built over water and fires set at the water’s edge (thus drawing the moisture through the chimney and into the air).

They’d believe anything, it seemed—especially in 1891, when a brutal drought continued to devastate Southern and Western Texas.

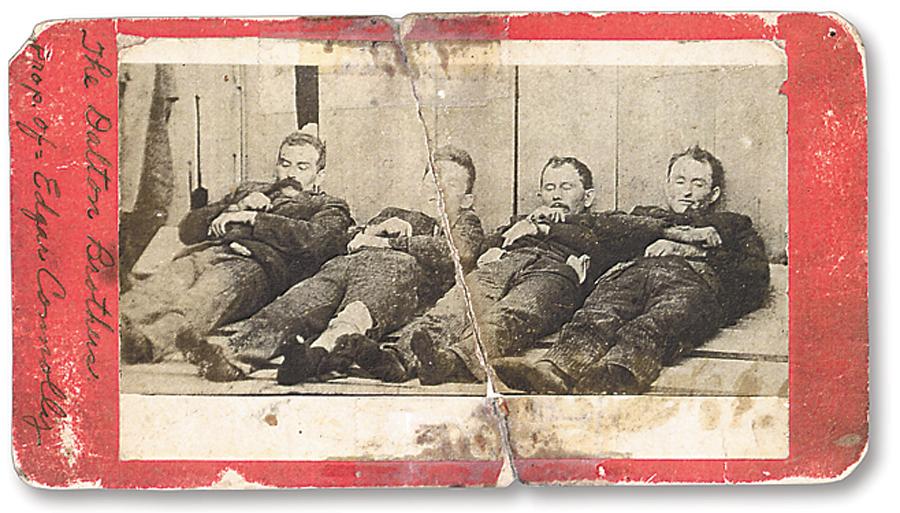

The drought of 1890-94 would be called the “Great Die” in South Texas. “The cattle wandering over the prairie perishing, how their lowing wrung my heart,” wrote Robert Kleberg, manager of the sprawling King Ranch southwest of Corpus Christi. The “Great Die” killed not only livestock, but also ranches, farms, banks and even towns.

Glory be—it rained

That summer and early fall, some Texans placed their hopes in the hands (and balloons) of government rainmakers.

At C Ranch, Dyrenforth’s team constructed 60 mortar-like guns and placed explosives in prairie dog and badger holes. They flew kites with dynamite sticks suspended from them by electrical fuses and tied the kite strings to brush. They launched hydrogen-filled balloons. And on August 9, they set off the explosions.

The next morning—glory be—it rained. For two hours, it poured, “causing water to run into the ‘draws,’ and the plains to be drenched,” Dyrenforth reported. It rained so suddenly, so unexpectedly, that the team had not bothered setting out any rain gauges, so Dyrenforth could only estimate that an inch had fallen.

Any celebration, however, ended when news arrived that it had also rained heavily in Abilene, well out of the concussion area.

Two days later, experiments resumed with light firing to conserve explosives. Rain, if any, was slight, but on August 25, the heavy bombardment resumed, stopping at 11 p.m.

“At about 3 o’clock on the following morning, August 26, I was awakened by violent thunder, which was accompanied by vivid lightning, and a heavy rainstorm was seen to the north,” Dyrenforth reported. “While the thin edge of the cloud was overhead, a few charges of dynamite were fired near the ranch house. A few moments after the first explosion the first overhead rain began, and after each subsequent explosion rain could be seen falling from the clouds overhead in what appeared to be a heavy shower, but the air was still so dry that at first no rain and afterward only a sprinkle reached the ground. After each explosion the quantity of rainfall increased…. The storm seems to have been entirely local.”

Dyrenforth headed back East to make his report, and in September, his crew departed Midland for El Paso, where Lt. S. Allen Dyer, of the 23rd Infantry stationed at Fort Bliss, commanded a detail ordered to assist the rainmakers.

Heavy bombardment began on September 18, but instead of it producing rain, Dyrenforth’s assistant John T. Ellis reported that “A heavy dew had fallen during the night, an occurrence which, I am reliably informed, had never been known before in that region.” Ellis later learned that “soon after midnight rain had begun to fall within a few miles of El Paso, to the south and southeast, evidently coming from the clouds which had formed over the city, during the explosions, and, between midnight and morning, a heavy rainstorm had passed down the Rio Grande valley, copiously wetting the valley, including a few miles of the contiguous portions of Texas and Mexico.”

The sky isn’t falling at King Ranch

Despite the promising report sent to Congress, the El Paso experiment ended abruptly due to a lack of materials. Yet, national periodicals, including Harper’s Weekly, Rocky Mountain News, Washington Post, Chicago Times and New York Sun, had taken an interest in the experiments. So had King Ranch’s Kleberg, who, along with Henrietta King, widow of ranch founder Richard King, agreed to pay an estimated $900 for explosives and equipment, and $746 for traveling expenses if the rainmakers came to King Ranch.

Dyrenforth’s rainmakers accepted, setting up at the South Texas village of San Diego, about 27 miles northwest of ranch headquarters. At 1 a.m. on October 16, with the Weather Bureau reporting an improbable chance of rain, the detonations began. The bombardment would continue for over two days. While the sky remained clear, many residents turned downright scared. On the evening of the 17th, people from San Diego and other communities “crowded together in a frightened mass” until they were assured the sky wasn’t falling and Texas wasn’t at war.

At 9:45 that night, the first balloon of the second evening of experiments ascended. Explosions continued at a rate of 10 a minute until 11:30 p.m. At 4 a.m., the last balloon exploded, and it began to rain. More charges were quickly set off, producing scattered drops. “In five minutes a steady rain was falling and in another ten minutes, the water was pouring down in torrents,” Ellis reported. When the shower ended before 5 a.m., a half inch had fallen.

The storm had been local and unpredicted by the Weather Bureau. Rainmakers thought they had made it happen, and they certainly made believers out of many South Texans.

“It affords me the greatest pleasure to say that I am satisfied with the result,” Duval County rancher H.J. Delamer wrote. “From what I saw and from what I heard from those who watched throughout the night, I am of the opinion that the rain which fell on the morning of the 18th, was produced by the explosions.”

Dr. Lincoln B. Wright of San Diego and Judge James O. Luby of Duval County concurred. “I feel safe in saying that you evidently produced rain, or, to be more explicit, that rain would not have fallen without the effects produced by your experiments,” Wright said. Luby added: “What was my surprise, after retiring for the night, to hear the patter on the shingles.”

On October 19, Dyrenforth’s team returned to Corpus Christi and disbanded. The project had cost about $17,000, of which the government paid $9,000.

Although skeptical, Kleberg said the tests seemed encouraging enough for further experiments. “There certainly is no subject of greater interest to our entire people than this,” he wrote, “for in almost all portions of the Union has there been suffering from drought this year.”

Yet, as quick as the weather can change in Texas, so turned Dyrenforth’s fortunes—and credibility.

While newspapers had been kind to the rainmakers, agricultural and scientific journals, such as Farm Implement News, Texas Farm and Ranch and Scientific American, ridiculed the experiments. Even Kleberg had doubts, saying he didn’t believe “these experiments which were made under the most adverse circumstances, have demonstrated, fairly and sufficiently, the theory whether or not rainfall can be produced by heavy concussions.”

Thus in the fall of 1892, “Cloud-Compelling” Dyrenforth’s team returned to Texas for a do-or-die round of warfare on weather. Setting up shop around San Antonio, Dyrenforth began blasting, destroying a mesquite tree and breaking hotel windows. It rained, too, only in Laredo—150 miles south.

University of Texas physicist Robert MacFarlane rejected the theory and experiments. The once-glorifying press and politicians said even nastier things, and the U.S. government dry-docked the rainmakers.

The theory of producing rainfall by concussion didn’t exactly die in Texas, though, until cereal czar Charles W. Post’s experiments between 1910-14 proved inconclusive.

And Dyrenforth? After the San Antonio debacle, he returned to Washington, saddled with an unsavory nickname for a self-styled rainmaker: Dryhenceforth.

Johnny D. Boggs came across the rainmaking experiment while researching his 2000 Republic of Texas Press book, That Terrible Texas Weather: Tales of Storms, Drought, Destruction, and Perseverance. The Southwest has been in a drought ever since.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the U.S. Senate –