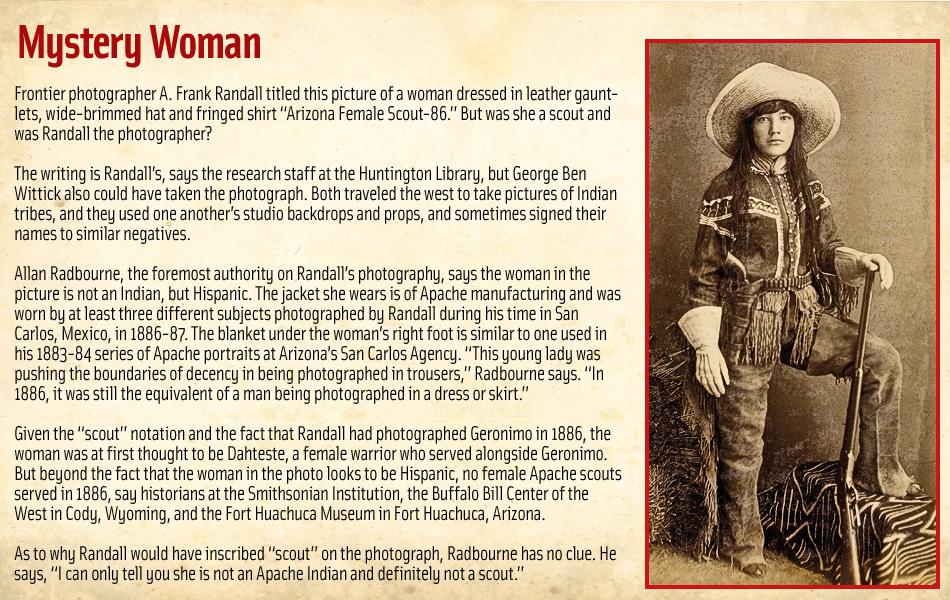

The image of strong women pioneers and trailblazers of yesteryear has grown hazy in the decades since the mass migration west. For many, the type of woman who dared venture into the rugged frontier is relegated to two categories: the corset-wearing soiled dove with the heart of gold who entertained in saloons or the forlorn schoolmarm who struggled to educate a community caught in survival mode in a world without law and order.

The image of strong women pioneers and trailblazers of yesteryear has grown hazy in the decades since the mass migration west. For many, the type of woman who dared venture into the rugged frontier is relegated to two categories: the corset-wearing soiled dove with the heart of gold who entertained in saloons or the forlorn schoolmarm who struggled to educate a community caught in survival mode in a world without law and order.

Dime novels were the first in a long line of news articles and books that helped narrow the view of the variety of women in the West down to a certain few colorful characters. Colonel Edward Zane Carroll Judson, who often wrote under the name of Ned Buntline, penned several popular dime novels in which the story centered on either a shunned lady from a house of ill repute or an old maid schoolteacher seeking love. One of his best-selling tales, The Secret Vow; or The Power of Woman’s Hate, involved a New Orleans madam who dreamt of traveling over the plains to teach orphan children how to read.

The fact is women in a variety of professions journeyed beyond the Mississippi to make new lives for themselves. Their backgrounds and ambitions were diverse and unique and as native to the wild territory as the eye-stretching plains and the great bowl of sky over those plains.

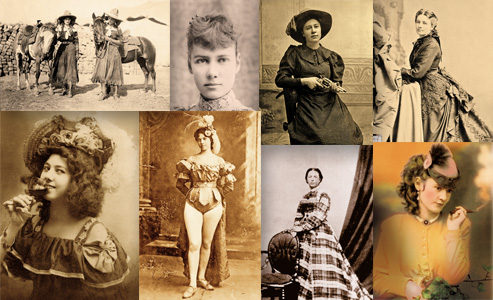

The Entertainers

While blazing the trails that would allow for settlement in the frontier West, fur trappers, Forty-Niners and frontiersmen were content with crude entertainment provided by ragtag bands and bear-wrestling and prizefighting exhibitions. In the impetuous atmosphere of tent cities, gambling dens, saloons, brothels and dance halls thrived, but miners and merchants soon longed for more polished amusements. Theatres, backstreet halls, tents, palladiums and jeweled-box-sized playhouses went up quickly and stayed busy, their thin walls resounding with operas, arias, verses from Shakespeare and minstrel tunes.

Many of the most popular women entertainers of the mid-and-late-1800s performed in boomtowns throughout the West. They were mostly well received and sometimes literally showered with gold. Lotta Crabtree was one such entertainer. She was six years old when her mother brought her to California in 1853 and eight when she began her career as a singer, dancer and comedy actor. Touring the mines and playing in little upstairs theatres or at the local opera houses, Crabtree, soul of mischief and merriment in all her roles, was Fortune’s favorite.

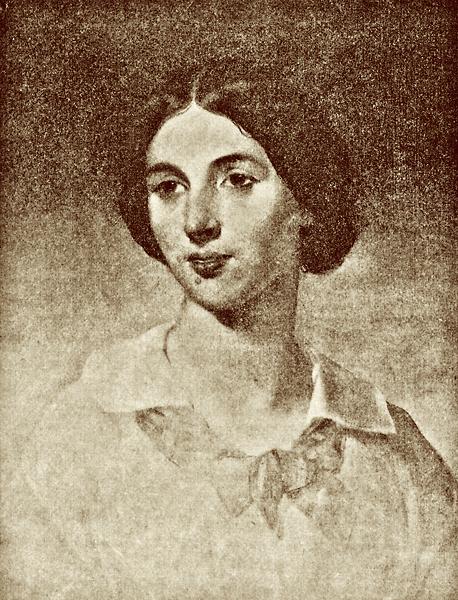

The spirited Lola Montez attracted thousands of starstruck audiences, who described her dancing as “heavenly.” An Irish lass born Marie Gilbert and trained in Seville as a Spanish dancer, Montez defied convention and wore flesh colored tights and knee-high dresses of flamenco that fanned out as she spun around the stage, stomping her feet to the music. Her personal life was as controversial as her dancing. She was involved romantically with French author Alexandre Dumas and King Ludwig I of Bavaria. One critic called Montez the “incarnation of brave wickedness and splendid folly.”

Kate Rockwell, known professionally as “Klondike Kate” or the “Flame of the Yukon,” endeared herself to audiences in Alaska, crooning songs of faraway places in her low, sultry voice. The feisty redheaded beauty dressed in a form-fitting, red sequin gown and played to packed houses nightly. She married a waiter, Alexander Pantages, who used the capital Rockwell earned performing in venues from Washington to Texas to purchase theatres and nickelodeons. Pantages eventually left his hardworking wife for a younger woman, taking all of Rockwell’s earnings with him. Not many know her name, but Pantages’s name can still be seen today on theatres in the United States and Canada.

One stage performer literally acted on behalf of her nation. Born Harriet Wood in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1833, Pauline Cushman spied for the Union Army during the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln commended her service. She died at the age of 60 and was buried in Officer’s Circle at the Presidio’s National Cemetery in San Francisco, California.

The Explorers

The uncharted Western regions of America were drawn and publicized by explorers of both genders.

Sacagawea, the young Shoshone woman who served as Lewis and Clark’s translator on their 1804-05 expedition, made the entire journey to the Pacific, and the return trip back to her Mandan village, with a newborn baby on her back. Many believed that, without her aid, the journey, commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson, would have ended in failure.

In 1843, Gen. John Charles Frémont led an expedition over the Rocky Mountains into Oregon. His wife, Jessie, the daughter of Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, transcribed his adventures onto paper for curious, westward moving settlers. Jessie also helped bring about the preservation of nearly 1,200 square miles of land in central California known as Yosemite.

Narcissa Prentiss Whitman recorded the hardships and experiences of life on the trail west in 1836, as she traveled with husband Marcus through the Oregon wilderness and the Walla Walla Valley in Washington. She and Eliza Spalding were the first white women to cross the Continental Divide. The Whitmans were Presbyterian missionaries who, along with the Spaldings, established Waiilatpu on the banks of the Columbia to minister to the Cayuse. Unfortunately, on November 29, 1847, after a measles outbreak had killed more than half the tribe, the Cayuse, believing the Whitmans had poisoned their people, killed 14 missionaries at the post, including Marcus and Narcissa.

The Activists

Women who right wrongs were just as prevalent out West as they were in the East. Activists ranged from Helen Hunt Jackson, who wrote about the unfair treatment of American Indians, to Donaldina Cameron, who rescued more than 3,000 Chinese girls and women from indentured servitude at her mission in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

One protest that echoed throughout the Wild West was Carrie Nation’s. For decades, the lives of women from coast to coast had been adversely affected by their husband’s, fathers’ and brother’s abuses of alcohol. The brickbat-, stone- and hatchet-wielding Nation was a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1874, to encourage wives and mothers to crusade against liquor. Smashing saloon tables and liquor barrels, Nation waged a one-woman campaign against saloons across Kansas and into Oklahoma. After destroying her first saloon in Kiowa, Kansas, and others in Wichita, the incident was hailed by flashy headline writers, reveled in by cartoonists and worn threadbare by poets. Amidst all their ridicule and burlesque, her sincere purpose stood out, marking Nation as the original advertiser of the fight against liquor.

The Teachers

Concerned parents who moved to the frontier realized that without good teachers, the children of the settlers would become orphans of progress. Daring female educators pushed beyond the boundaries of the Mississippi River to teach frontier boys and girls how to count, read, write and mend a pen. Lacking schoolbooks, Eliza Mott taught the alphabet using inscriptions on tombstones. Olive Mann Isbell and Hannah Clapp came to class armed with guns to keep students safe from hostile natives. Rosa Maria Segale, however, spread her teachings to the wider public.

Born in Italy in 1850 and brought to America when she was four, Segale became a nun, Sister Blandina, who pursued her first westward assignment as a teacher in Trinidad, Colorado, and Santa Fe, New Mexico. In her diary, published in 1932 as At the End of the Santa Fe Trail, Sister Blandina recorded her encounters with vigilantes and outlaws. Even as she chastised those who took the law into their own hands, she cared for the wounded criminals. In the late 1870s, she gave aid to a member of Billy the Kid’s gang, Happy Jack, after four other doctors had refused to help. The Kid wanted to kill them, but Sister Blandina discouraged him. This wasn’t William Bonney, but Arthur Pond, alias William LeRoy, who also went by the nickname. The outlaw later remembered the sister’s act of kindness and refrained from robbing a stage she was on after recognizing the nun on board.

The Warriors

As American Indians waged war on the frontier against settlers, some courageous women fought alongside their men. In 1876, two such women were Buffalo Calf Road Woman, who saved the life of her brother during the Battle of the Rosebud, and Moving Robe Woman, one of the warriors who led the counterattack against the cavalry that proved a death knell for Gen. George Custer and his men.

One warrior who fought with her intelligence was Warm Springs Chief Victorio’s sister Lozen, whose wise council Geronimo sought before his raids on Mexican villages or on U.S. Army soldiers determined to capture the Apache leader and his followers. In 1886, Lozen, along with Geronimo and his men, surrendered. She was among the Apache ringleaders shipped by train from Fort Bowie, Arizona, to a prison at Fort Marion in Florida. She never saw her homeland again; Lozen died of tuberculosis in 1889.

Courage on the battlefield was not limited to Indians. Outside a couple assumed noncombatants and some couriers, the only survivors of the dark and bloody 1836 Battle of the Alamo were the widows of several Texian defenders and a number of children, and not because they had all hid away from danger. While the Texians hoped for reinforcements to arrive, Susanna Dickinson nursed soldiers wounded during the conflict. She was shot during the siege, and her Army officer husband was killed. Susanna held her infant daughter, Angelina, the “babe of the Alamo,” in her arms when she informed Gen. Sam Houston that the Alamo had fallen.

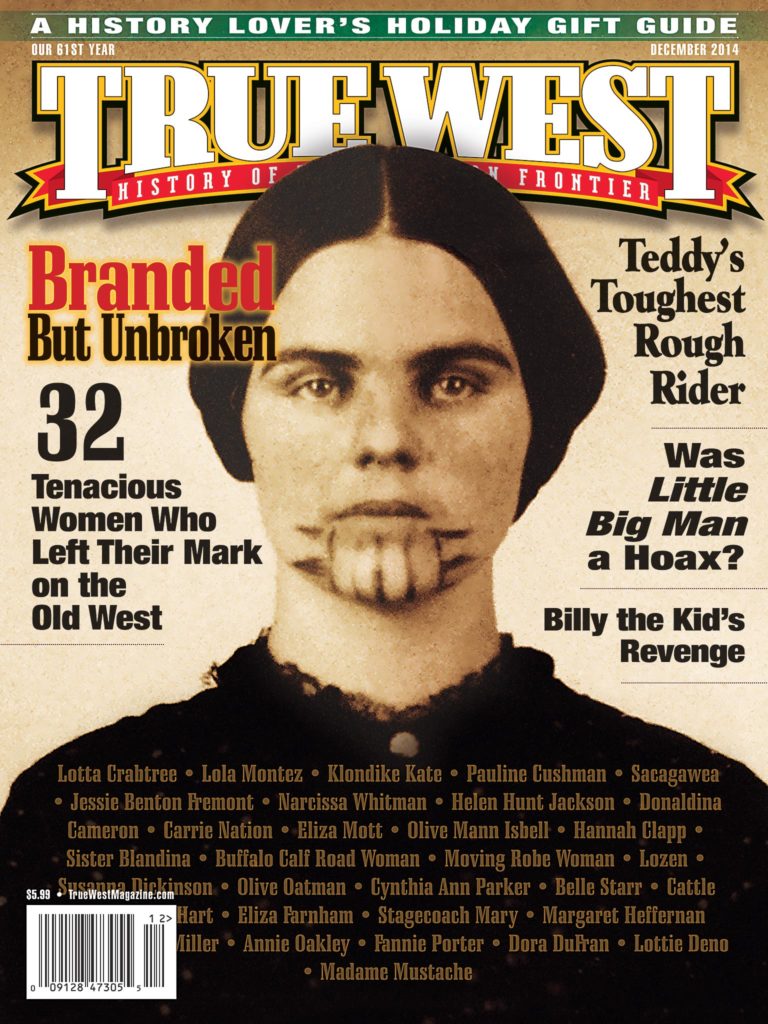

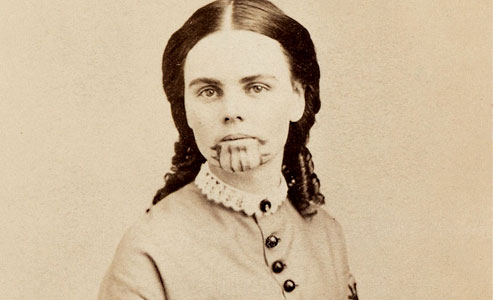

The Captives

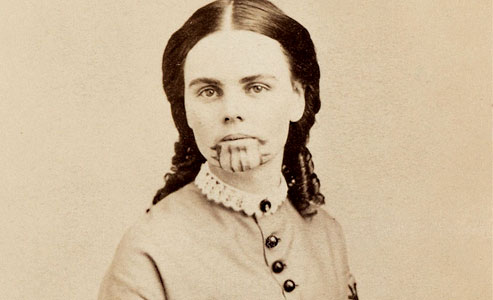

Present-day Gila Bend, Arizona, is the scene of one of the greatest tragedies of early pioneer days. On March 19, 1851, a band of Yavapais slain a father and mother, and four of the seven children of the Oatman family. The youngest son, Lorenzo, scalped and tossed over a cliff, survived the ordeal. The two daughters, Mary Ann and Olive, were taken hostage. After a harrowing year of hunger with the Yavapais, the girls were sold to the Mohaves for two horses, blankets and vegetables. Olive lived through another four years with the Mohaves, who treated her like family and marked her like they did the other women in the tribe, tattooing blue lines on her chin that ran from her mouth, as well as her arms. Tragedy struck when famine came in 1855, and Mary Ann died. The Mohaves released Olive in the spring of 1856. She reunited with her brother, Lorenzo, and the pair moved to Oregon to live with their cousin. Despite Rev. Royal Stratton’s attempt to twist Olive’s story in Captivity of the Oatman Girls, the love she had for the Mohaves bled through his pages and in the public lectures she gave. Olive married John B. Fairchild in 1865, and nearly 40 years later, on March 20, 1903, she died in Sherman, Texas.

Another female captive, Cynthia Ann Parker, was nine years old when she was taken as a hostage after Comanches, Kiowas, Caddos, Wichitas and Kichais attacked the homestead of Silas M. Parker in central Texas on May 19, 1836, killing several of the settlers living there. Parker stayed with her Comanche captors for nearly 25 years. The bride of Chief Peta Nocona, she had three children with him. In December 1860, Texas Ranger Sullivan Ross and his men attacked Chief Nocona’s camp, killing the chief and a number of braves. The rescued Parker was returned to her white relatives near Birdville and then lived with her brother in Van Zandt County. She wasn’t happy, and she didn’t want to stay there. Nocona’s people were her own, and she grieved for the free life of the plains.

The Outlaws

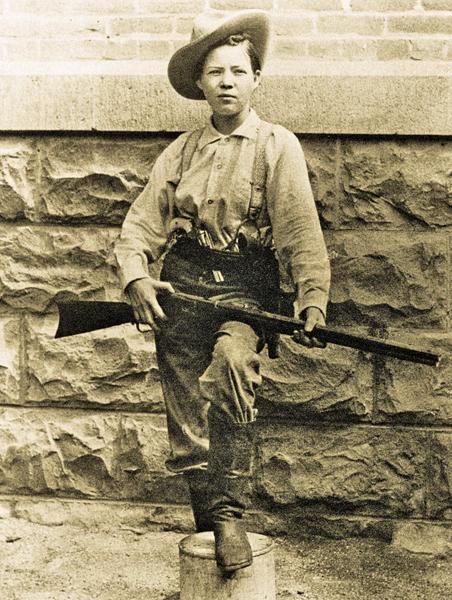

They were the kind of bad women who the good women tried to run out of town on a rail. Some sported pink ostrich feathers and yards of lace and tulle, with as neat a boned-in waistline as you could want and a steely-eyed glitter demanded by her trade; others wore buckskin shirts and trousers and made their point at the end of a gun. Whether wicked by nature or choice, female renegades resisted the law-abiding life.

Belle Starr, raised by a wealthy, well-educated father with a background in judicial affairs, rejected respectability for a life of crime and immoral adventures. She was romantically involved with murderers, and her home in Oklahoma was a refuge for criminals. In 1883, Judge Isaac Parker, the hanging judge, in Fort Smith, Arkansas, sentenced Starr to a year behind bars for stealing horses. After she was released early from jail, she was arrested for various crimes from 1886 to 1889. Starr came to a bad ending. On February 3, 1889, as Starr was returning to her home outside of Eufaula, an unknown gunman shot Starr off her horse and then fatally shot her in the face.

Cattle Kate Watson’s demise was also violent and controversial. Ellen Watson owned property next to her paramour, Jim Averell, near Rawlins, Wyoming. Her nickname came from the unfounded accusation that she accepted stolen cattle from cowboys in return for sexual favors. In actuality, she did nothing more than mend their clothes and she had legally purchased her cattle. On July 20 1889, she and Averell were lynched by an angry mob. The Salt Lake Tribune commented, “The men of Wyoming will not be proud of the fact that a woman—albeit unsexed and totally depraved— has been hanged within their territory. That is about the poorest purpose a woman can be put to!” Although the journalist twisted the knife in with his “unsexed and totally depraved” comment, many shared his outrage over the hanging of a woman—the only woman our nation ever lynched for cattle rustling.

Not all female bandits, or those suspected of banditry, died horribly. At least, we think that to be true of Pearl Hart, one of the last bandits to rob a stagecoach and the only woman ever recorded as having committed that crime. Details of her life are sketchy after she left prison, but Arizona lore has her living a peaceful life until her death in 1955.

Born in 1871, in Canada, Pearl Taylor loved dime novels, particularly the stories about bandits Dick Turpin and Jack Sheppard. Her surname comes from Frederick Hart, whom she married at 17. She left him in Chicago, headed to Colorado in 1893 and found a paramour in miner Joe Boot, who shared Pearl’s fascination with crime.

On May 30, 1899, the couple held up a stage that ran between Globe and Riverside. Pearl was sentenced to five years, while Boot got a 30-year sentence. But Pearl was released early, on December 15, 1902, after serving nearly three years. The reason is unclear, but the conditions included an agreement on Pearl’s part to leave the state until the term of her sentence had expired. She went to Kansas City, Missouri, appearing as the Arizona Bandit in a play by that name, before she eventually moved back to Arizona.

The Businesswomen

Eliza Farnham was the first woman to recognize the effect women could have on the Wild West. In 1849, she organized a party of marriageable women to travel to California to meet lonely, eligible bachelors. Charging the women $250 to make the journey, Farnham petitioned single ladies to move west to meet and hopefully marry men of means and, in doing so, tame the evils of drinking and debauchery that had overtaken it. Farnham’s unconventional methods of bringing civility to the Wild West helped transform the frontier into a land fit for wives and families.

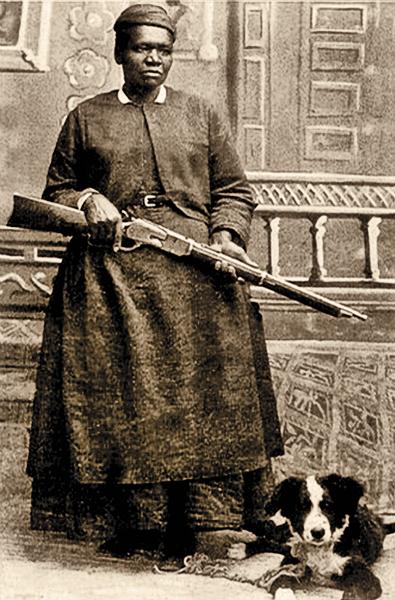

That frontier welcomed former slave Mary Fields who, in her 60s, was hired as a mail carrier in Cascade, Montana, because she was the fastest applicant to hitch a team of six horses. Texas rancher Margaret Heffernan Borland led a cattle drive in 1873. F.M. Miller worked as the only female deputy in the Indian Territory in 1891. Annie Oakley traveled the world as one of Buffalo Bill Cody’s sharpshooters. And yes, women like Fannie Porter and Dora DuFran ran brothels and women like Lottie Deno and Eleanora “Madame Mustache” Dumont gambled and won big. The pioneer women’s trades could be respectable or shady, just like the men’s.

Chris Enss is a New York Times best-selling author who has written more than 20 books on the subject of women in the Old West. Her most recent title is Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women.

Photo Gallery

Cynthia Ann Parker holds her daughter, Topsannah, in 1861, a year after Texas Rangers had rescued them from the Comanches who captured her in central Texas nearly 25 years earlier. She made several unsuccessful attempts to flee to her sons, Pecos and Quanah. The latter carried on his mother’s legacy as the last free Comanche chief, serving as a link between whites and Comanches.

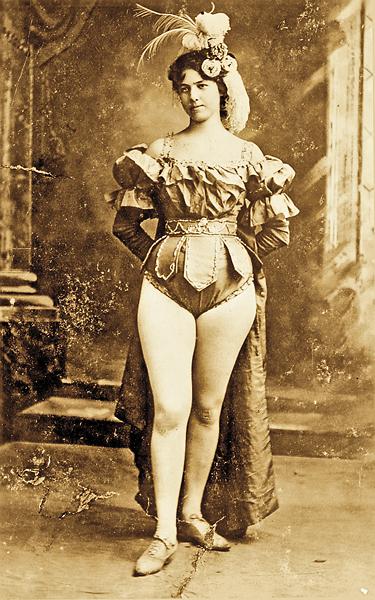

At the age of 15, dance hall girl Dora DuFran promoted herself to madam and began operating a brothel in Deadwood, Dakota Territory. She even hired Calamity Jane as a cook and wrote about her in Low Down on Calamity Jane: “She took more on her shoulders than most women could. She performed many hundreds of deeds of kindness and received very little pay for her work.”

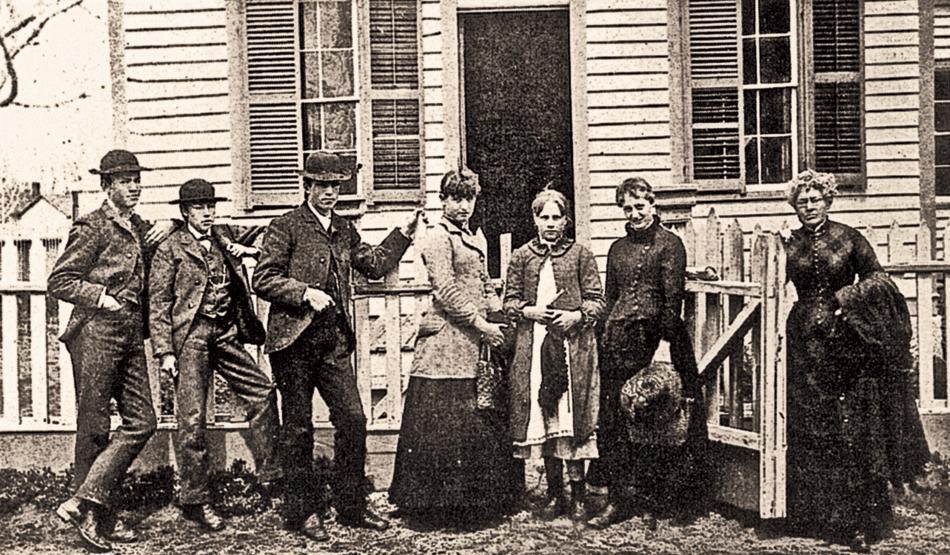

Hannah Clapp, owner and principal of the Sierra Seminary founded in Carson City, Nevada, in 1861, stands at far right. Mark Twain visited the school in 1864 and incorporated his observations of Clapp’s teachings in his famous 1876 novel, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

–All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

The 10-gauge shotgun-toting postal worker, Mary Fields, spent the first 30-odd years of her life in slavery before she became the first black woman to carry the U.S. mail, in her stagecoach, starting in 1895, when she was in her 60s.