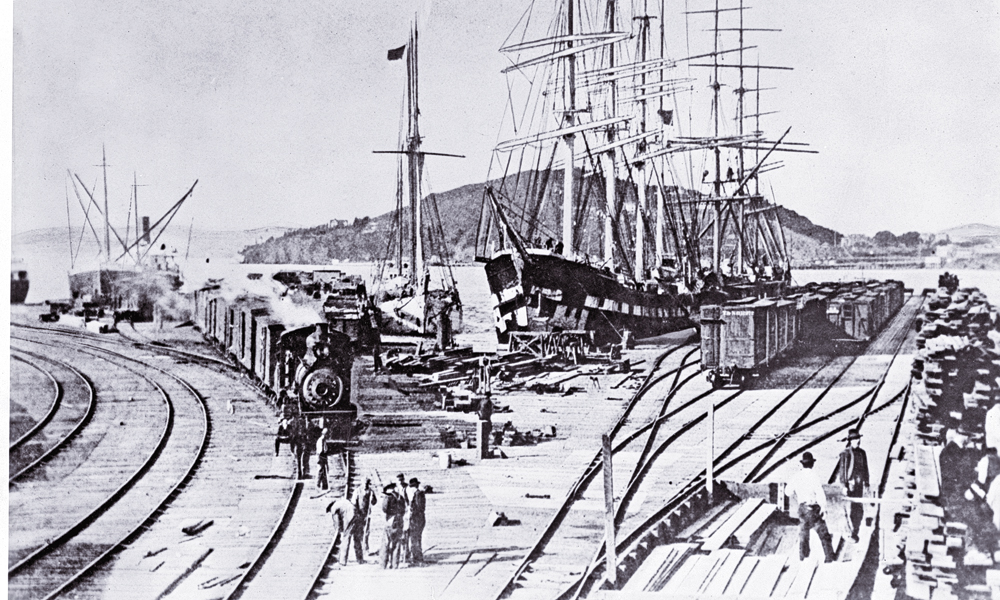

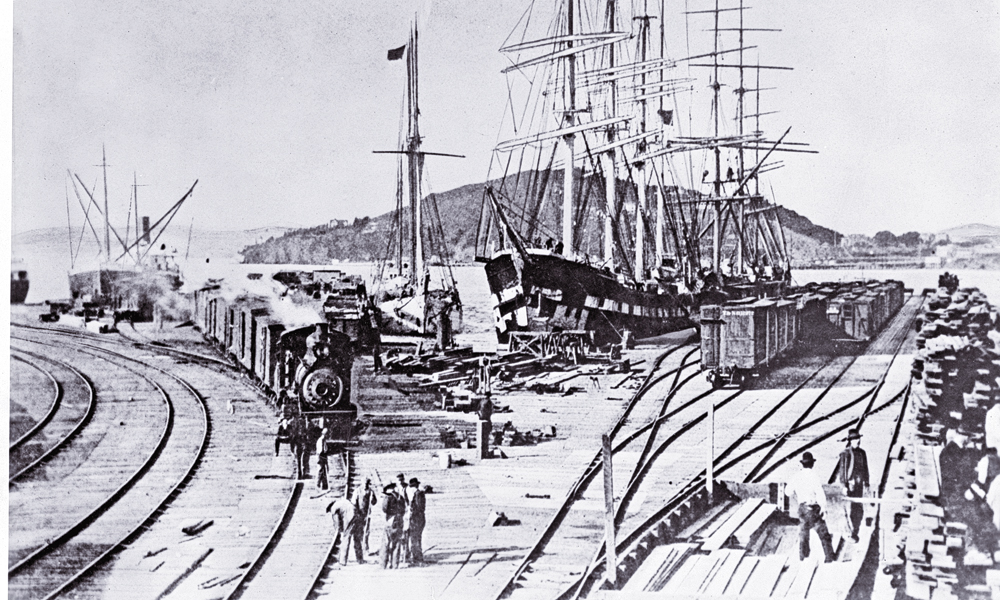

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

A century and a half ago, steel rails began stretching across the landscape to link this nation. In an 1832 article published by the New York Courier, Dr. Hartwell Carver advocated construction of a transcontinental railroad from Lake Michigan to Oregon. Fifteen years later he sought a public charter from Congress to build such a railroad.

Congress finally took action in 1856 when the Select Committee on the Railroad and Telegraph in the U.S. House of Representatives endorsed a Pacific Railway bill, writing: “The necessity that now exists for constructing lines of railroad and telegraphic communication between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of this continent is no longer a question for argument; it is conceded by everyone. In order to maintain our present position on the Pacific, we must have some more speedy and direct means of intercourse than is at present afforded by the route through the possessions of a foreign power.”

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law in 1862, and construction started in 1863. Although Carver had proposed a railroad from Lake Michigan to Oregon, this first transcontinental railroad would be a line between Omaha and San Francisco. It became the joint effort of three private companies, all of them largely supported by federal funding in the form of bonds and tremendous land grants.

The Western Pacific Railway Company would build a line between Oakland and Sacramento, California. The Union Pacific would construct the railroad from Omaha west to Utah. The middle link was under development by the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California. This latter enterprise, planned by Theodore Judah, was financed and managed by Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Collis Huntington and Mark Hopkins. They became known as The Big Four, or The Associates. These California businessmen were the driving forces behind the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR), but thousands of Chinese laborers built the 690-mile line from Sacramento to Promontory Summit in Utah.

The Dream Begins in Sacramento

A good place to start a tour of this route is at the California State Railroad Museum in Old Sacramento. Rolling stock, such as the Central Pacific Railroad’s Gov. Stanford locomotive No. 1, is on display among the exhibits that highlight the development plans and construction of the CPRR. This car, built in 1862 in Philadelphia, was disassembled and shipped from Boston to San Francisco in 1862, making the trip around Cape Horn in crates. Once reassembled in California, it pulled the first excursion train of the CPRR in March 1864, and also the first scheduled passenger train that April. This museum has a variety of rolling stock, extensive exhibits, and shows the film Evidence of a Dream, all of which give you a good understanding of the Central Pacific.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Heading east, the highway grade on Interstate 80 from Sacramento to the summit of the Sierra is not all that precipitous, but as you begin the descent down the east flank of the mountain range into Nevada, it becomes steeper, and more scenic.

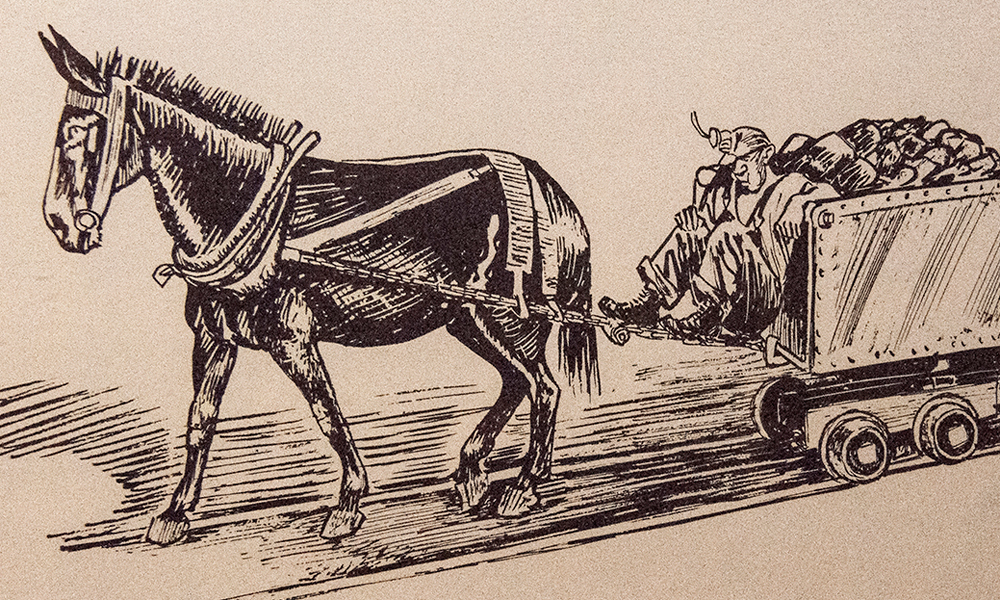

This was the highest point on the Central Pacific line. Of course trains don’t do that well on steep inclines and the descents necessary to go over mountain ranges, so Lewis Clement engineered a route through the mountains. Using black powder and nitroglycerin—plus the back-breaking labor provided by Chinese workers—Clement punched a dozen tunnels through the granite. The laborers worked from both sides—

east and west, meeting in the middle with a precision that was—and remains—an engineering marvel. At times the Chinese lowered themselves from ropes slung from the top of the mountain peaks. Once they had drilled and packed the black powder charges into the rock, they lit fuses and then ascended their ropes to get out of the way of the explosion. Of course, many died due to accidents in construction and the effects of often brutal winter weather.

The Central Pacific construction proceeded slowly. Only about 50 miles of track were laid in the first two years. But by the summer of 1868, at least 4,000 workers, most of them Chinese, had made it across the Sierra and descended to the Great Basin.

On to Nevada

Our route takes us on I-80 east as it drops down from the summit of the Sierra Nevada to Reno, Nevada, and then stretches across the Great Basin through Winnemucca,

Battle Mountain, Elko, and Wells. This highway—and the railroad route—parallels the California Trail, which was literally put out of business when the railroad completed its link at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869.

For railroad history in Nevada, visit the Nevada Railroad Museum in Carson City, where you can take a ride on a 1905 steam locomotive, the Virginia & Truckee #25, or one of the museum’s other cars—a 1910 McKeen Motor Car and a 1926 Edwards Motor Car. They operate most weekends through the summer into October, and some weekends during October and December. The museum itself is open Thursday through Monday.

The Humboldt Museum in Winnemucca has a collection of early vehicles, including some horse-drawn wagons and early automobiles. To learn about the earlier wagon migrations across the region, visit the California Trail Interpretive Center, just west of Elko.

The highway route diverts from the original line of the Central Pacific, as I-80 stretches across Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats and into Salt Lake City. This also parallels the route of today’s rail line across Utah and Nevada. If you want to ride the rails today, you can do it on Amtrak’s California Zephyr (just don’t plan any specific arrival times as the train is not always on time).

The Nation United at Promontory

To see where the Union Pacific and Central Pacific finally linked the nation in 1869, continue north out of Salt Lake City on I-15 to Ogden and then to Brigham City, Utah, before turning west on UT 83. This road, and another spur road, will give you views of the original grade, cuts and fills along the Central Pacific route, before reaching Promontory and the Golden Spike National Historic Site.

The truth is, you have to really want to visit Promontory because it is pretty far from the well-traveled interstate highway and can be a long diversion for which you will most likely have the road almost to yourself. However, the opportunity to stand for which the railroads connected the nation in those pivotal years after the Civil War is absolutely worth the drive.

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

Chinese and Irish workers laid the last ten miles of track and some were still on hand when dignitaries, a band and a cheering crowd came out for the driving of the golden spike.

A report published on May 15, 1869, in San Francisco, provided a description of the celebration at Promontory: “J.H. Strobridge, when the work was all over, invited the Chinese who had been brought over from Victory for that purpose, to dine at his boarding car. When they entered, all the guests and officers present cheered them as the chosen representatives of the race which have greatly helped to build the road…a tribute they well deserved and which evidently gave them much pleasure.”

The Central Pacific Railroad and Union Pacific Railroad truly united the nation at a time when such a link was essential, not only for the symbolism it represented that the United States was connected, but also for the economic opportunities the line represented. Now it was possible to transport freight and families. The journey west from the Missouri River that once took nearly six months by wagon could now be done in less than two weeks. It was a remarkable achievement, and is a lasting reminder of how determination and hard work come together for great good.

Candy Moulton spends her time on the road, exploring the West, and once in a while, actually hangs her hat at her home near Encampment, Wyoming.