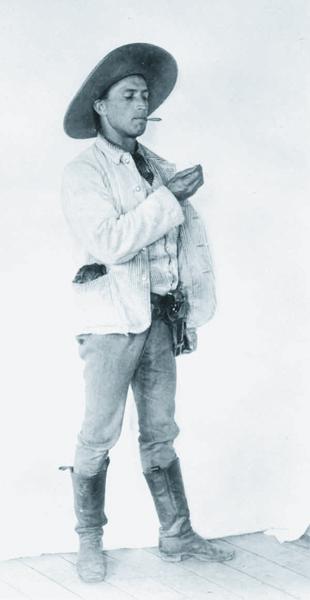

The 26 year old’s decision to walk across the West seemed pure folly to some: “What a picnic those fellows out in the plains will have with the seat of Lummis’s breeches.”

Nonetheless, Charles Lummis endeavored to walk from Cincinnati, Ohio, all the way to Los Angeles. More than half a century before Jack Kerouac hit the road in a Hudson, this tough little writer went in search of the “beatific” on foot.

He brought little but curiosity and a pen with him. Only a small revolver and, later, a hound named Shadow would keep the young man constant company. As an Easterner, the West held much mystery to Lummis. On assignment from The Los Angeles Times and his former employer, the Chillicothe Leader, Lummis would write a letter a day detailing his 1884-85 journey. These letters were published in a book, A Tramp Across the Continent, in 1892.

Adventure and experiences found Lummis. In the depths of winter, starving while crossing New Mexico, Lummis relied on the kindness of a stranger for food. New to the West, of course, Lummis had little knowledge of its customs and foods. So when the kind stranger placed a steaming heap of mysteriously stewed tomatoes in front of him, Lummis took a substantial bite. “And then I sprang up with a howl of pain and terror, fully convinced that these ‘treacherous Mexicans’ had assassinated me by quick poison. My mouth and throat were consumed with living fire and my stomach was a bit of boiling torture. I rushed from the house and plunged into a snowbank.” Lummis should have asked for the red. (Chile that is. Lummis had unknowingly consumed the New Mexican spice.)

The Mexican gentleman with the fiery taste buds, however, was just one of the many characters Lummis encountered during his odyssey across the West. Although Lummis would continue on to weave fabulous tales detailing many of these unique people, none of them impacted the journalist as much as the Indians of the Southwest. The people of New Mexico’s pueblos especially struck a chord with the young Lummis.

When he finally reached the terminus of his trip in Los Angeles, Lummis found himself a bit empty. His work for The Los Angeles Times generally made him an unqualified success, but his young spirit demanded an exit. He took to Arizona as a war correspondent for the renewed Apache Wars, covering Gen. George Crook’s campaign to capture Geronimo. The former athlete became so adept at tracking that he was actually invited to return as a scout. His terrifically busy schedule for the Times precluded that chance, but Lummis did not forget his love of the Southwest. He wrote and published books on its peoples, and he edited publications such as Land of Sunshine, the predecessor to today’s Sunset magazine.

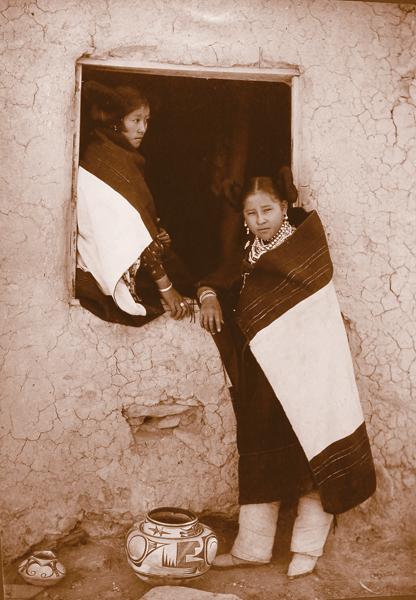

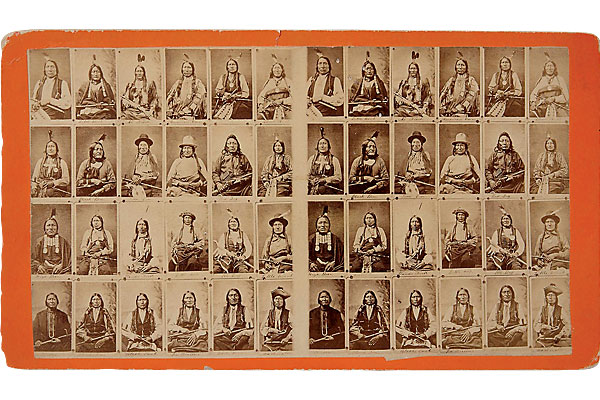

Lummis especially loved New Mexico and often returned to visit, even though a recent onset of paralysis rendered the left side of his body useless. Despite this debilitating condition, Lummis captured his fascination with the locals on film. He took numerous pictures of the pueblos and their inhabitants, and even lived among the people of Isleta Pueblo for a time.

His numerous articles and books on the Southwest may have made Lummis famous, but his photographs capture his admiration for these people. Lummis’s images are not, nor have they ever been, as impactful as those taken by Edward S. Curtis, but they do radiate a sense of intimacy that certainly originates from Lummis’s proximity and attachment to the subject of these photos.

Lummis took photographs of these people because he truly empathized with their trials and tribulations. He helped secure rights for Indians, beginning with liberating Indian children torn from their families and forced to attend an Indian school in Albuquerque. Like much of the nation, Lummis had subscribed to the Carlisle School’s policy of “kill the Indian, save the man.” But after living among the people of Isleta Pueblo in New Mexico during the late 1880s, he saw the forced Indian education as an abomination. In 1901, he formed the Sequoya League, which was dedicated to “make better Indians by treating them better.” The last battle he fought before his death in 1928 was advocating for Indians’ religious rights when the Bureau of Indian Affairs threatened to stop them from dancing.

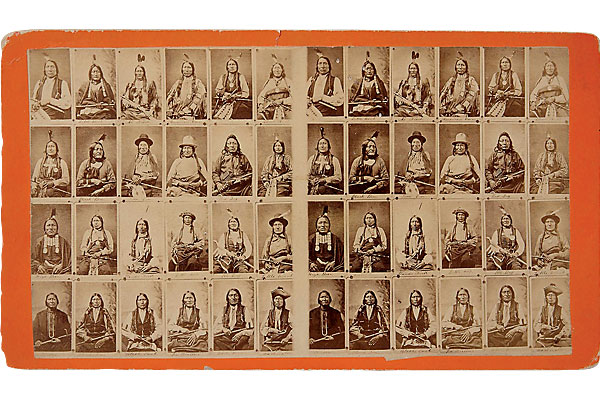

Some of his photos, part of the collection of Southwestern memorabilia that Lummis gifted to Los Angeles’s oldest museum, the Southwest Museum he founded 100 years ago, are on display at the Autry National Center as part of the “Picturing the People” exhibit through January 27, 2008. Featured along with Lummis’s photographs are other images of Indians taken by outsiders.

To counteract the limited viewpoint of these outsiders, the curators at the Autry have introduced international native photography via its showcase of the touring exhibit “Our People, Our Land, Our Images.” In preserving authentic representations of Indians, both historical and contemporary, the Autry has successfully carried on Lummis’s work to ensure the survival of Indian culture.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Braun Research Library, Southwest Museum of the American Indian, Autry National Center / Gift of Mrs. Eugene Clark –

– Courtesy Braun Research Library, Southwest Museum of the American Indian, Autry National Center –

– Courtesy Braun Research Library, Southwest Museum of the American Indian, Autry National Center / Gift of Mrs. Agnes C. Allerton –

– Courtesy Braun Research Library, Southwest Museum of the American Indian, Autry National Center / Charles F. Lummis Collection –

– Courtesy Southwest Museum Purchase Fund, Braun Research Library, Southwest Museum of the American Indian, Autry National Center / Collected by Mr. Frank A. Robertson –

– Courtesy Braun Research Library, Southwest Museum of the American Indian, Autry National Center –