At 10 p.m. on September 7, 1878, Little Wolf, Dull Knife, Wild Hog and over 300 Northern Cheyenne warriors, women and children fled Darlington Agency in Indian Territory.

At 10 p.m. on September 7, 1878, Little Wolf, Dull Knife, Wild Hog and over 300 Northern Cheyenne warriors, women and children fled Darlington Agency in Indian Territory.

They were going home to the northern plains. These people had been removed from the northern plains in May 1878 to a place that became a hellhole, where hot, sultry air combined with disease and starvation to decimate them.

While more than 950 Northern Cheyennes had been moved to the Darlington Agency near Fort Reno, by the time they fled the area in September, fewer than 350 survived.

Returning to their homelands

Their nine months of deprivation had begun on November 25, 1877, in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming where federal troops under command of Col. Ranald MacKenzie attacked Dull Knife’s village. They slayed dozens and then burned lodges and personal possessions. The Cheyennes fled that attack on foot into an icy, snowy mountain landscape and successfully eluded the troops for a time. But by the spring of 1878, they had surrendered, and most were at Red Cloud Agency in western Nebraska where negotiations led to their removal to Indian Territory.

But the bands led by Dull Knife, Wild Hog, Little Wolf and Old Crow never fit in at the Darlington Agency, which also served the Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos, and the northern tribal members isolated themselves in an area not far from the agency itself for the month they were in Indian Territory. Conditions were horrible. Deaths occurred regularly. The headsmen finally agreed they would rather die trying to reach their homelands on the northern plains, than remain near Darlington. With some horses taken from Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos, the Northern Cheyennes fled during the night of September 7, 1878.

The Cheyennes’ 750-mile, 44-day trek would take them across western Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska before federal troops finally succeeded in stopping their flight, killing many and imprisoning others at Camp Robinson. Even then the story was not finished.

Fleeing Darlington Agency

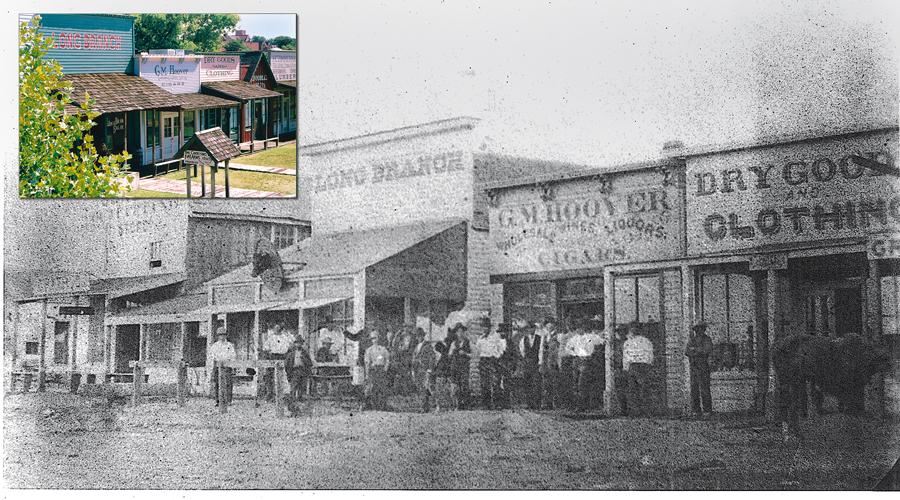

We will begin our trek along the Northern Cheyenne trail in western Oklahoma at the site of the Darlington Agency and Fort Reno, both near El Reno west of Oklahoma City. Two original buildings remain at Darlington Agency, six miles northwest of El Reno, while there are some 30 structures at nearby Fort Reno. Darlington Agency was established August 10, 1869, and the site is now part of the Darlington Game Bird Hatchery. Fort Reno, meantime, served as a cavalry outpost established in 1874 to protect the Darlington Agency.

From here the Northern Cheyennes fled northwest, engaging in a battle at Turkey Creek and fighting with a group of salt haulers in what is now western Oklahoma. Troops sent in pursuit of the fleeing Indians rode from Fort Supply, an old military base of operations. Our route is along the Canadian River following U.S. Highway 270 west to Woodward, Oklahoma, and then continuing past Fort Supply to U.S. 283 and traveling north to Dodge City, Kansas.

Raiding through Kansas

Little Wolf occupied the small community of Meade, Kansas (southwest of Dodge City on U.S. 160), for several hours before he and his followers crossed the Arkansas River near present-day Cimarron.

Additional troops organized at Fort Dodge, south of present-day Dodge City, and followed the Indians north, eventually engaging in a battle in late September at Punished Woman’s Fork, just north of Scott City. To follow the trail, take U.S. 50/400 west from Dodge City to Garden City and then travel north on U.S. 83 to Scott City.

The Cheyennes raided all along their route, gathering food and other supplies, including horses, and in many cases killing settlers, particularly in western Kansas in the area around Oberlin along Sappa and Beaver Creeks. The Last Indian Raid Museum in Oberlin (on U.S. 83) is devoted to the Cheyenne raids along the Sappa watersheds. From Oberlin, the Cheyenne Trail continues north along U.S. 83 to McCook, Nebraska, where the trail crosses the Republican River and then follows the Frenchman before turning north.

Splitting ranks in Nebraska

Additional troops had organized at Sidney Barracks in Nebraska shortly after the Indian break on September 7. Located on the Union Pacific Railroad line, Sidney Barracks had access to trains that could carry troops east or west to intercept the Cheyennes should they make it this far north.

Major Thomas Tipton Thornburgh of the Fourth Infantry (who would die in the 1879 White River battle with the Utes in Colorado) failed to stop the Cheyennes, who crossed the railroad just east of Ogallala and then disappeared into the Sand Hills.

With troops closing in from various directions, the Indians then split their ranks. Little Wolf and his band headed toward Powder River and eventually made it to Montana, while Dull Knife, Wild Hog, Old Crow and their followers turned toward Red Cloud Agency, expecting to find sanctuary with Red Cloud and other Lakotas. While the Cheyennes had been in Indian Territory, however, the government had moved Red Cloud Agency from its earlier location on the White River in western Nebraska to a site along the Missouri River.

In a foggy accident on October 25, troops from Maj. Caleb H. Carlton’s Third Cavalry, based at Fort Robinson, stumbled onto the camp of Dull Knife and Wild Hog. Following tense negotiations, the Indians were taken into custody and moved to Camp Robinson, where they were held in a wooden barracks.

To follow the route of the Northern Cheyennes across Nebraska take U.S. 6 west from McCook to Imperial then turn north on Nebraska Highway 61 and follow it through Ogallala and into the Sand Hills. Turn west at Hyannis on Nebraska Highway 2 to Alliance and then travel north on U.S. 385 to Chadron and west on U.S. 20 to Crawford and nearby Fort Robinson.

Dull Knife surrenders

Sergeant Carter P. Johnson was with the troops involved in the surrender of Dull Knife’s band. He later told Indian Wars historian Walter Mason Camp, “Dull Knife said his people were hungry, and if we would give them something to eat, they would follow. We set out some rations, and the Indians took them and followed us. This was about 10 a.m. We went down into the valley and camped that night on Chadron Creek. Dull Knife’s band camped in the creek bottom and we had only two companies at that time camped on both banks right over them.”

Buffalo Hump was with Dull Knife and also later told Camp about the Cheyenne surrender: “When Dull Knife surrendered, there was no firing on the part of either soldiers or [Indians]…. When they surrendered, most of them gave up their arms, but a few concealed them under their clothing and in this way retained possession.”

At Camp Robinson, the Cheyennes were placed in a guardhouse and initially treated well. A guard was posted outside the building, and there were additional guards inside the barracks “with a sentry pacing up and down, armed with a six-shooter, among the Indians,” Sgt. Johnson recalled.

In the early days of the Cheyennes’ incarceration, a soldier prepared food for the Indians. The women and children were allowed to go freely outside the barracks, while the men were allowed outside under guard. “The Indians were pleasant and agreeable to their guards inside and often talked and smoked with us in the little room. They had their dogs with them in the barracks and a heating stove, and were comfortable enough,” Sgt. Johnson said.

Change of plans in Nebraska

The atmosphere changed when orders came to once again remove the Cheyennes to Indian Territory. The tribespeople made it clear that they would die first. When negotiations with headsmen failed, Capt. Henry W. Wessells removed Wild Hog and Old Crow from the barracks and cut off food, water and fuel supplies to the people remaining in the building. Lacking basic supplies, the Indians “now became very ugly to the inside guards, having changed their demeanor completely, and were getting to be very unruly,” Sgt. Johnson said.

There was soon talk that the Cheyennes intended to break out once again. Troops were on heightened alert while the Indians sang and danced, tore up the floor of the barracks and barricaded the windows. Tribespeople who had earlier been allowed outside picked up corn that had rattled through the floorboards of the post storehouse. This may have been their only food, although Johnson believed the Cheyennes also may have killed and eaten some of their dogs.

After dark on January 9, 1879, the Cheyennes were suspiciously quiet. “I declared then and there that they were getting ready to come out,” Sgt. Johnson said. Upon hearing the first gunshot later that evening, Johnson ordered his men toward the fort: “We doubled-quicked to the fort, over a mile away, not waiting even to fully dress.”

“When it became evident that the soldiers intended to starve us to death, we thought we might as well die fighting as to starve—so it was decided to break out,” Buffalo Hump recalled. “The soldiers had boarded up their windows of the guardhouse and built a fence around the house a little way from it, and guards were patrolling outside the fence. When the time came to [break] out, I busted the boards from the window and was first out, and knocked a hole through the fence with an ax. A fight started right there.”

Once out of the barracks, Buffalo Hump joined his mother and sister as well as Dull Knife and other members of the band. “We were out 10 days without anything to eat, and we nearly perished,” he recalled. Eventually some of the 149 Northern Cheyennes, including Buffalo Hump who had been held at Camp Robinson (which became Fort Robinson in the fall of 1878), made it to the Pine Ridge Reservation (on the Nebraska state line in southwestern South Dakota), where they found refuge. Sixty-four Indians were killed and another 20 wounded during the outbreak from Fort Robinson, while 11 members of the Third Cavalry died and 10 were wounded.

The barracks where the Cheyennes were held have been re-created, and many of the original Camp/Fort Robinson buildings are still in place at the site that is now a Nebraska State Historical Park. You can even stay at the fort, with accommodations in some of the original fort structures.

Candy Moulton is a regular contributor to True West. She researched this article at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, and at the Denver Public Library.

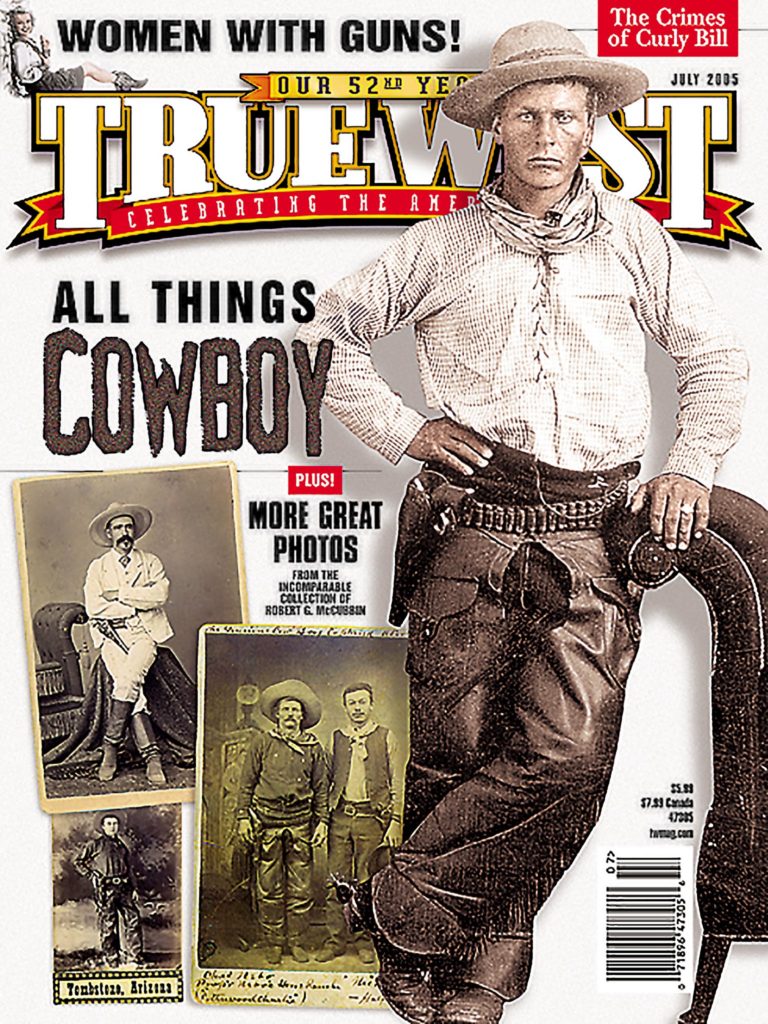

Photo Gallery

– Above: Kansas State Historical Society; Left: By Candy Moulton –

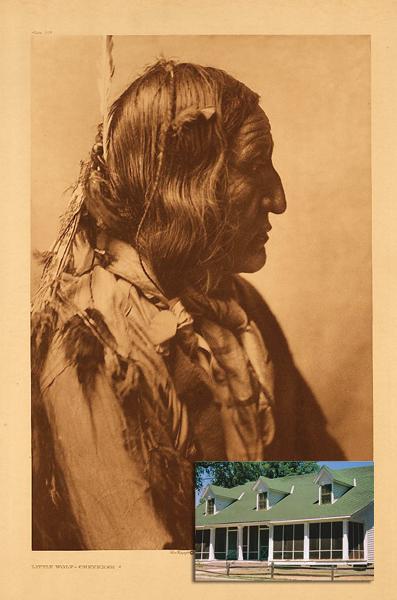

– Left: True West Archives / Edward S. Curtis; Inset: By Candy Moulton –

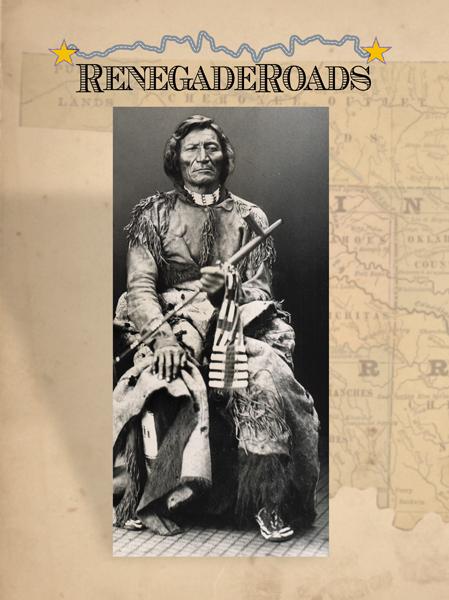

– True West Archives –

– By Candy Moulton –