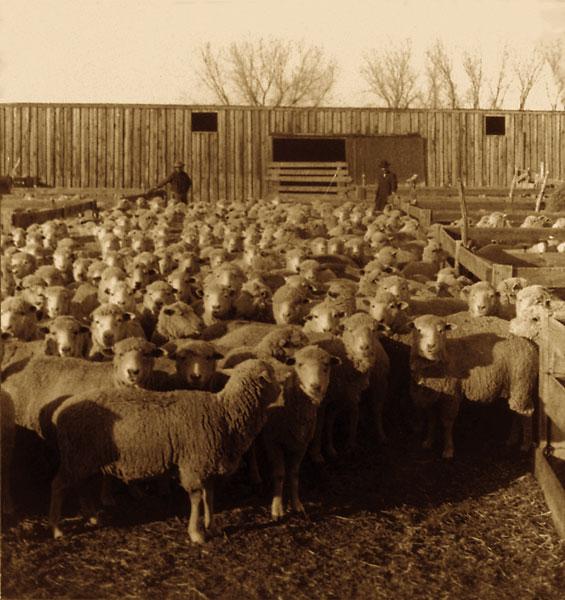

You wouldn’t know it today when you drive across Colorado and Wyoming, seeing cattle grazing with sheep herds nearby, that a century ago such juxtaposition was not only unusual, but, in many cases, very, very unwelcome—sometimes deadly.

You wouldn’t know it today when you drive across Colorado and Wyoming, seeing cattle grazing with sheep herds nearby, that a century ago such juxtaposition was not only unusual, but, in many cases, very, very unwelcome—sometimes deadly.

Range wars flared up for a number of reasons: conflict between large cattle ranchers and homesteaders; disagreement between ranchers over water rights; and then there were the sheep and cattle wars.

Cattlemen did not like sheep because they believed the smaller animals with their sharply pointed hoofs cut the range grasses and made the ground stink so that cattle wouldn’t use it. Quite simply, they did not want to share the range. But certainly some ranchers saw sheep as an opportunity, another way to turn grass into a commodity in the form of meat or wool.

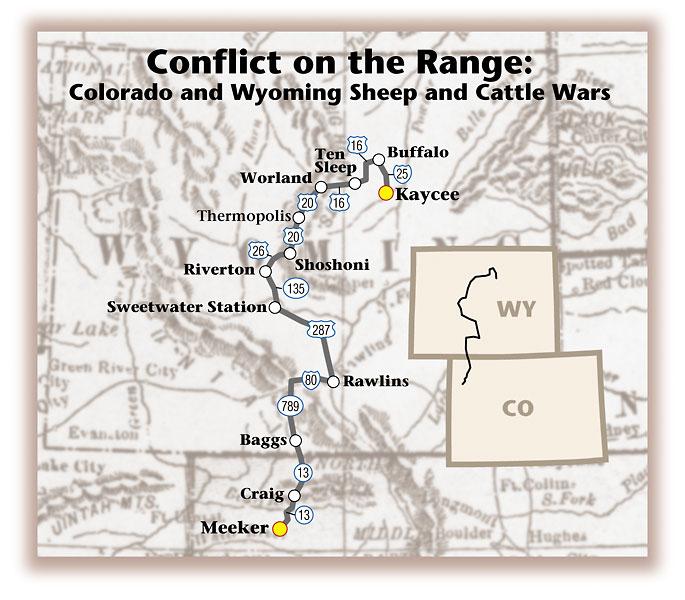

Stockmen came to the area around Craig, Colorado, to establish cattle ranches, but in the early 1890s, sheep started moving onto the range trailing south from Wyoming where they had been raised for some 20 years. The first large herds in southern Wyoming were headquartered out of Rawlins, in part because of the Union Pacific Railroad and its ready way to ship animals to markets, and also because of the large areas of rangeland to the south and west.

The sheep summered in the Sierra Madre Range in 1894 and then moved down into Colorado, where conflict already brewed. In an area south of Craig and Meeker, 3,800 sheep were stampeded over a bluff into Parachute Creek. Herder Carl Brown tried to keep the raiders from rushing the sheep over the cliff and was shot in the hip. When a posse from Parachute, Colorado, went to the area, the men found a mass of dead sheep at the foot of a 1,000-foot bluff; climbing up the narrow trail, they found the wounded Brown.

“The owners are residents of Parachute with rights to the adjacent range and the posse made a futile race to apprehend the raiders. John Miller owned seventeen hundred of the sheep and Charles Brown, uncle of the wounded man, twenty-one hundred,” the Craig Courier reported on September 14, 1894.

Colorado Protests Wyoming Sheep

Many of the sheep moved north out of Colorado for the winter as they were trailed to desert country in south-central Wyoming, where they could endure conditions that weren’t so harsh as the situation would be if they remained in the northern Colorado mountain valleys. But when spring had melted the snow in 1895, the sheep again moved south through Wyoming to graze along the Little Snake River. Everyone expected they would soon push into Colorado. The Colorado cattlemen responded quickly, passing resolutions in May 1895 that prohibited sheep from entering the Yampa River Valley. A showdown was on the way.

The Cheyenne Leader of May 23, 1895, reported that four days earlier, “riders were sent out to scour the country and warn the settlers that sheepmen now holding their flocks on Snake River at the Wyoming line, were contemplating an invasion of the Bear River cattle ranges. The effect was electrical, and by noon today fully 350 cattlemen and feeders were assembled to decide upon positive action to keep the sheep back….”

At community meetings cattle owners unanimously adopted resolutions outlining the “danger to cattle and ranchers by a sheep invasion,” the Leader reported. In all cases the resolutions prohibited sheep from grazing or being herded through the “country drained by the Bear River, which includes all the territory from the Continental Divide west to Utah….” In essence sheep were not allowed anywhere in northwestern Colorado.

But, the Leader went on to report, “It is believed that the sheepmen will disregard the warning of the stock raisers, and attempt to drive through the forbidden territory, fattening their mutton as they approach the railroad [in Colorado], depending on state aid in the protection of their rights.”

To forestall such action, the “stock feeders and cowboys, with a force of eight hundred to a thousand (men) are holding themselves in readiness forcibly to resist any advance made south of Hahn’s Peak by the sheep owners,” the newspaper reported. “A war is imminent and unless the more conservative heads prevail, the rifle will figure a conspicuous part in a Routt County sheep war. The sheep that are causing the trouble are some sixty thousand head belonging to J. G. and G.W. Edwards and others in Wyoming.”

By early June armed men in Hayden prepared to defend their range in Colorado. “Since daylight troops of cavalry have been dashing into town [Hayden] at short intervals from all directions, representing every settlement of the county east of the established sheep country,” the Leader reported on June 2, 1895. “During the day fully two hundred armed men, representing the ranching and cattle industries, arrived in town, soon to disperse and scatter for the night among the ranchmen in the vicinity of Hayden for a distance of five miles on each side of the town.”

The cattlemen organized in military fashion electing a “general” and 10 captains who would command companies of “soldiers” with “quartermasters” appointed to wagon trains to provide supplies for the campaign. The Leader reported that the “marching force” would make its way toward the sheep camp where some 40,000 animals were believed to be grazing at the headwaters of Elkhead Creek. Further, the paper stated, people from Hayden to Steamboat had heard a “wild rumor” that 150 Pinkerton detectives were even then riding toward the sheep camp to support the sheepherders.

The Leader correspondent concluded, “It is now midnight, and the campfires about the single street of the town in front of two or three store buildings have a warlike appearance. About fifty men are in bivouac in an open field near town, and sitting about camp fires in the midst of stacked guns.”

On the Trail of the Range Wars

My journey through this area of conflict in northwestern Colorado starts in Meeker, where, on September 7-11, you can get a firsthand look at the skills of sheep dogs. The Meeker Classic Sheepdog Championship Trials draws some of the top dogs and dog handlers in the country and gives everyone a chance to see how these animal athletes do their job. I recommend you take your own lawn chairs. While in town, you should make a stop at the White River Museum.

Then head north on Highway 13 to Craig and its Museum of Northwest Colorado. You’ll see exhibits related to the outlaws, lawmen and cowboys who worked in the area, as well as an outstanding photograph collection.

Continue north on Highway 13 to enter Wyoming at the town of Baggs, then turn east on Wyoming Highway 70 to Savery, which is little more than a spot in the road, but the location of the Little Snake River Museum. Located in the former Savery schoolhouse, this home-grown museum has other historic buildings, including the Brown House, once the headquarters for the Cow Creek Sheep Company. You’ll also see a good collection of historical photographs reflecting the early sheep raising history of this area.

Conflict in Little Snake River Valley

Little Snake River Valley is one of those areas where sheep raising continues. You’ll likely see small farm flocks as you travel along Highway 70, while large range herds are usually present in the open country north and west of Baggs and Savery.

The dispute of 1895 may have been diffused in Colorado, but, in this part of Wyoming, folks made constant threats to local sheepmen who threatened to cross into northern Colorado. Jack Edwards wanted to move his sheep south so that he could load and ship them from Colorado rail heads operated by the Denver & Rio Grande. Yet in April 1896, Edwards acknowledged the sheep and cattle lines established for the range, pledging to “do all in my power to protect such lines given to cattlemen and ranchmen, against any foreign sheep that may try to cross the lines agreed upon.”

That spring newspapers in the region published continued warnings of potential violence against the sheep and their herders. In late June, Edwards, who had moved some of his sheep into Colorado, received reports that his herders there had been killed and his sheep scattered. He rode horseback toward where he knew his flocks were on the Colorado range. A party of masked men ordered him to move the sheep off the range.

Although Edwards did back away from confrontation that summer of 1896 by withdrawing his ewes and lambs, he told an Omaha reporter on January 23, 1897, that whenever the cattlemen sent word that they would be “coming over to clean me out.… I have assembled my men and stayed there. I have an armed force of about fifty ready for the clash when it comes. I am compelled to keep a small army about my place all the time. A short time ago three hundred sheep were killed and two herders; for a while it looked as though the entire Colorado militia would have to be called out, but the sheepmen and cattlemen looked out for themselves, and there are several graves in the vicinity of Meeker that go to show that they know how to do this.”

One such violent incident took place on the morning of November 15, 1899, when 40 masked men rode up to a camp on the lower Snake River, clubbing and scattering 3,000 sheep. After taking the herder’s effects from the wagon, the masked men demolished it.

Drive east through the Little Snake River Valley and into the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest to see where the range disputes in this area finally wound down. When the National Forests were transferred to the Department of Agriculture in 1905, the change resulted in federal government regulation that divided this area of range between sheep and cattle interests.

Approximately 21 miles east of Savery, turn north onto Deep Creek Road. This route, which becomes Highway 71, takes you across range sheep country to Rawlins. A note about the road, though: It is dirt part of the way and not accessible year round. For an all-weather route, you should return to Baggs and take Highway 789 north to I-80 and then travel east to Rawlins.

The Carbon County Museum in Rawlins details the early sheep industry in the area. It has a significant collection of photographs related to the range sheep operations. If County Historian Rans Baker is in, you will have the chance to listen to many stories about the big sheep companies that were headquartered here in a county that was once the third largest range sheep production center in the nation (behind only Texas and Wyoming).

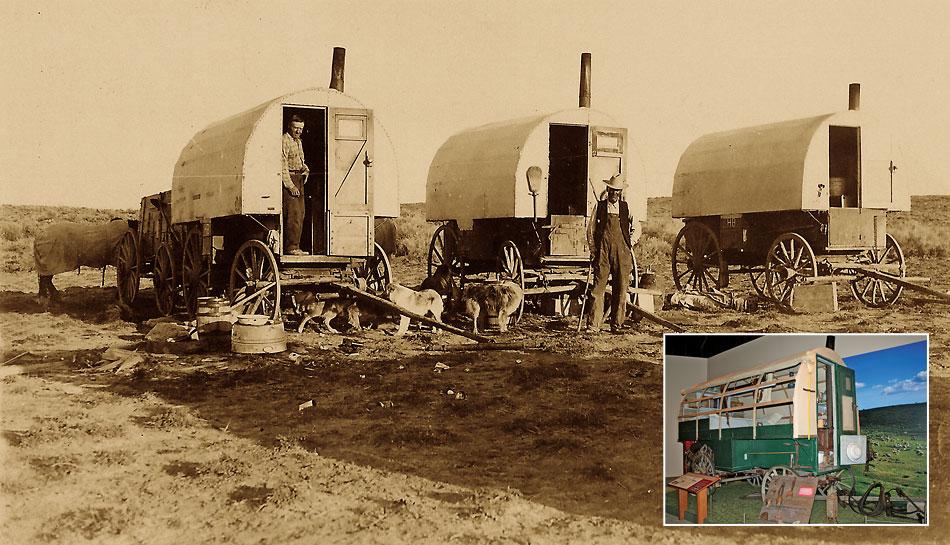

From Rawlins, get back on U.S. 287 and then follow the route to Sweetwater Station, Riverton and Shoshoni, until you reach Worland, where the Washakie Museum & Cultural Center has a sheep wagon and display of other sheep ranching memorabilia. Sheep wagons have served herders since the 1880s, when the first canvas-covered home on wheels was developed in Rawlins. The museum also presents information about the Spring Creek Raid.

Spring Creek Raid

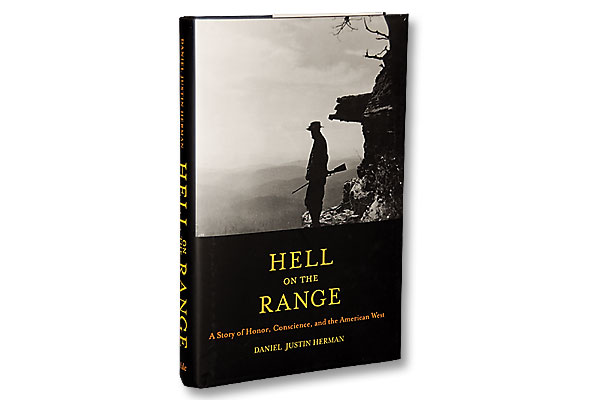

A couple dozen attacks against roaming sheep herds and herders took place across Wyoming from 1879 until 1909, featuring at least half a dozen killings with some 18,000 head of sheep slaughtered by being shot, stabbed, clubbed, poisoned, driven over cliffs and through other means as cowboys raided sheep camps. The only direct conviction for a killing associated with raids on sheep camps involved sheepman William Jones, who was found guilty of second-degree murder for the death of cattle rancher John D. Adams in Sheridan County in 1893.

Of course Tom Horn, a stock detective working for the large cattle operations, was convicted and hanged for the 1901 killing of 14-year-old Willie Nickell, the son of a sheepman. But no raid on a sheep camp was involved in that incident.

On Spring Creek, south of Ten Sleep, on April 2, 1909, however, raiders attacked the camp of sheepman Joe Allemand, his herder Joe Emge and his nephew Jules Lazier. When authorities inspected the camp the following day, they found the dead men; Allemand was shot, while Emge and Lazier were found in the sheepwagon, burnt beyond recognition. The raiders also killed 25 head of sheep and two dogs; another 2,500 head of sheep were scattered.

This would be the last major attack on sheepmen in Wyoming, in part because, although the Bighorn Basin was still isolated and had a frontier essence, law and order was coming to the region. Let’s also not forget the tenacity of the local county prosecuting attorney, Percy Metz, who made it his mission to gain a conviction in the case. Ultimately he did; five men were sentenced to prison. But that came only after a contentious trial in which the Wyoming National Guard had to provide security for the court and its officers.

When Herbert Brink and his cowboy compatriots were found guilty of the raid at Spring Creek and sent to the penitentiary in Rawlins, the killing of sheep and sheepmen in Wyoming stopped. Although other raids took place in 1911 and 1912, no more sheep raisers were murdered.

The conflict over the range itself would simmer until the Taylor Grazing Act was put into place in 1934, which provided for a federal lease for the open range, thereby separating sheep and cattle herds.

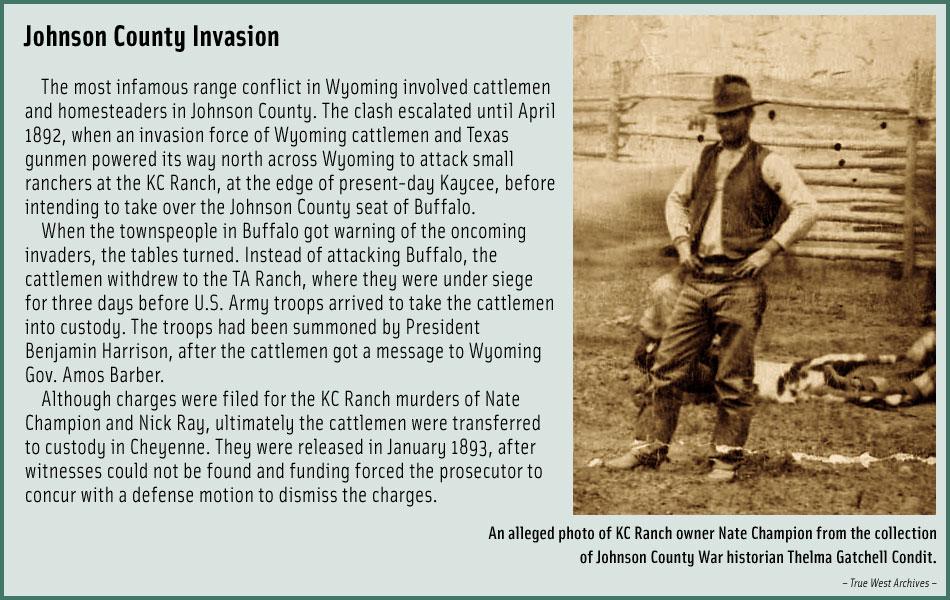

Johnson County Invasion

The most infamous range conflict in Wyoming involved cattlemen and homesteaders in Johnson County. The clash escalated until April 1892, when an invasion force of Wyoming cattlemen and Texas gunmen powered its way north across Wyoming to attack small ranchers at the KC Ranch, at the edge of present-day Kaycee, before intending to take over the Johnson County seat of Buffalo.

When the townspeople in Buffalo got warning of the oncoming invaders, the tables turned. Instead of attacking Buffalo, the cattlemen withdrew to the TA Ranch, where they were under siege for three days before U.S. Army troops arrived to take the cattlemen into custody. The troops had been summoned by President Benjamin Harrison, after the cattlemen got a message to Wyoming Gov. Amos Barber.

Although charges were filed for the KC Ranch murders of Nate Champion and Nick Ray, ultimately the cattlemen were transferred to custody in Cheyenne. They were released in January 1893, after witnesses could not be found and funding forced the prosecutor to concur with a defense motion to dismiss the charges.

To learn more about the Johnson County Invasion (also called the Johnson County War), you should visit the Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum in Buffalo and the Hoofprints to the Past Museum in Kaycee. Two books worth reading are The Johnson County War by Bill O’Neal and Wyoming Range War by John W. Davis.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

On the trail of the Colorado and Wyoming sheep and cattle wars.

– Above: Carbon County Museum, Rawlins, Wyoming; Inset: by Candy Moulton –

– By Candy Moulton –