The Cherokee Kid is the most famous cowboy Indian known today.

His real name was Will Rogers, and he was born in 1879 on a cattle ranch in the Cherokee Nation that later would become Oologah, Oklahoma. His unsurpassed lariat feats would earn him a listing in the Guinness Book of World Records for throwing three lassos at the same time: the first rope caught a running horse’s neck, the other looped the horse’s four legs and the last lassoed the rider. Americans everywhere had a chance to see his talent in the 1921 movie, The Ropin’ Fool.

Yet there were many unsung cowboy Indians who were also corralled on reservations throughout the West in the 19th century. Anyone who knows their Indian rodeo history would recognize Jackson Sundown, the Nez Perce nephew of Chief Joseph, who began competing when he was in his 40s and won the world championship in 1916. In Canada, the best-known early rodeo star was Tom Three Persons, a Blood from Alberta who won the World Bucking Horse Championship at the first Calgary Stampede in 1912.

The rodeo story is one of survival. It allowed reservation Indians to turn their agricultural duties into a salvation of their customs and tribal values. Horses and cattle allowed Indians to demonstrate “virtues such as bravery, generosity in gift giving, and respect for the natural world” and the “rodeo resonated with their own cultural priorities of being with family and community members, in the outdoors, and on horseback,” writes Allison Fuss Mellis in the University of Oklahoma Press book, Riding Buffaloes and Broncos: Rodeo and Native Traditions in the Northern Great Plains.

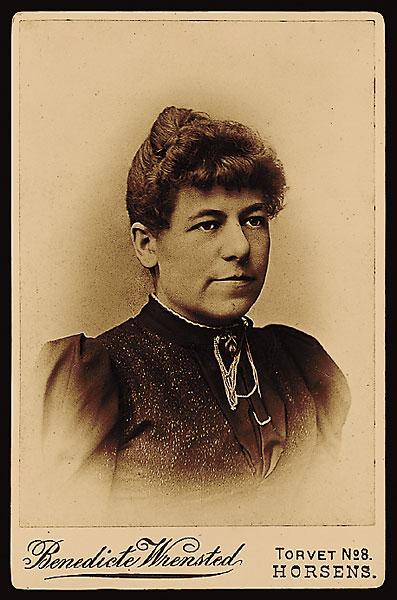

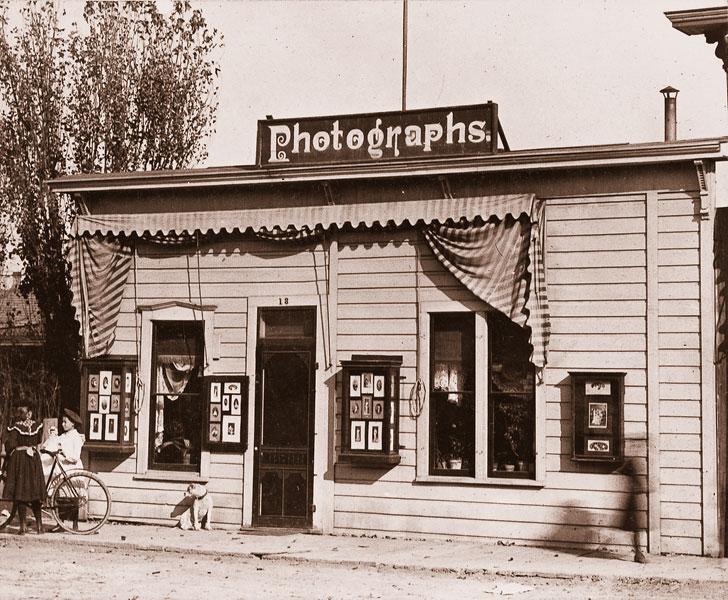

Oklahoma Press also introduced us to Benedicte Wrensted, a Danish photographer of Shoshone and Bannock Indians on the Fort Hall Reservation from her studio in Pocatello, Idaho. Wrensted was born in Hjorring, northern Denmark, on February 10, 1859. She moved to the U.S. in 1892, after her father died, and finally settled at the age of 36 in Pocatello. She took over “Hower’s Old Stand,” run by county surveyor A.B. Hower whose work on the Fort Hall Reservation had already made the studio a popular spot with local Indians. Wrensted worked as a photographer in Pocatello for nearly 20 years, as stated in her retirement announcement in the May 18, 1912, issue of the Pocatello Tribune.

Her work is special mainly because she was a commercial photographer. She had only the sitters in mind, making portraits of them that would suit their needs—unlike the famed Indian pictorialist Edward Curtis, who captured Indian life of more than 80 tribes during 1896 to the 1930s. Curtis was revealing a “vanished race” to the world. But he never visited Fort Hall. Photographers who did visit the reser-vation included William Henry Jackson. Bannocks and Shoshones do not appreciate his views of their ancestors as Jackson made them appear to be destitute and backward. But they do appreciate Wrensted’s work, says Bonnie Wuttunee-Woolsworth, then director of the Shoshone-Bannock Museum, in Joanna Cohan Scherer’s book, A Danish Photographer of Idaho Indians.

Scherer’s book is a touching history of Wrensted’s life and her relationship with Fort Hall Indians. This photo essay is courtesy of both Scherer’s book and the U.S. National Archives collection from which Scherer culled many of her images for the book. Our favorite photos in Wrensted’s collection are those showing cowboy Indians at Fort Hall. These are the ranchers whose tribal ties the federal government tried to subdue, but never could.

Photo Gallery

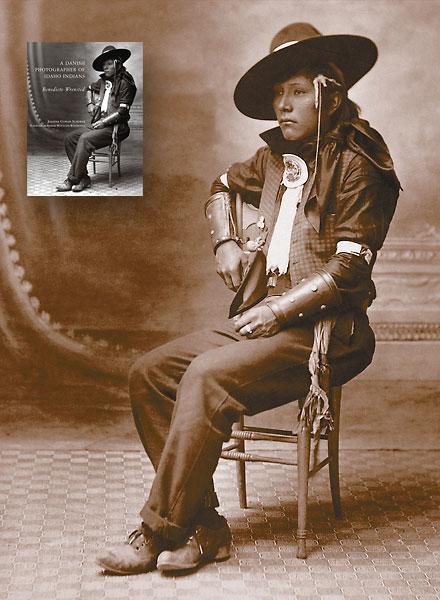

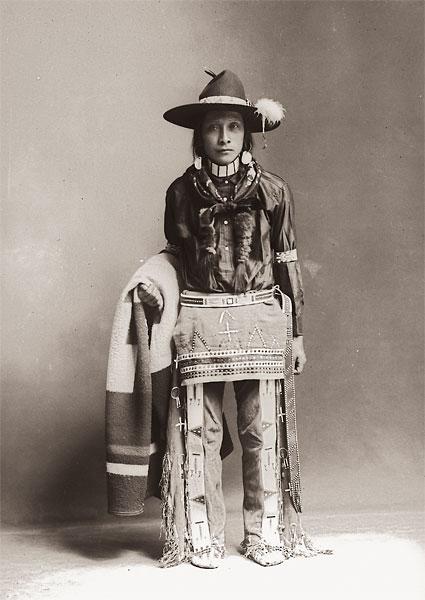

Although donning a reservation hat, this cowboy Indian prefers to show off his traditional costume. He is also wearing a breastplate choker, tied off with his rancher’s neckerchief.

– Courtesy U.S. National Archives –

Drink wears clothing representative of the more well-to-do Sho-Ban ranching cowboys on the reservation. He was featured on the cover of Joanna Cohan Scherer’s book, A Danish Photographer of Idaho Indians, available from the University of Oklahoma Press (oupress.com/800-627-7377).

– Courtesy University of Oklahoma Press/Idaho Museum of Natural History, Ruffner Collection, 274 –

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution, Handbook of North American Indians Project, Sherwood Collection –

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution, Handbook of North American Indians Project, Sherwood Collection –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch, 75-SEI-80 –

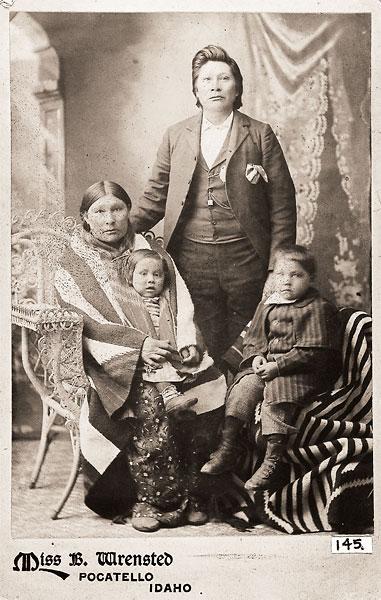

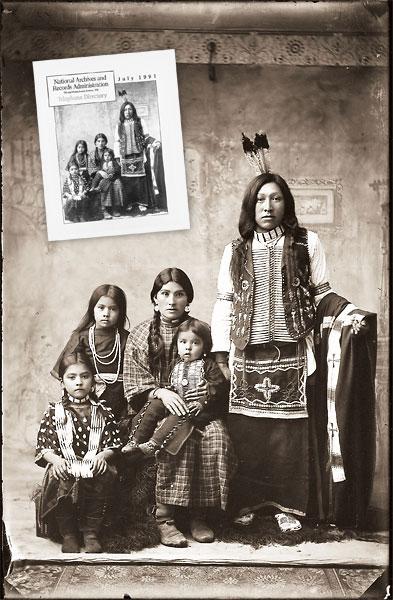

“He wears his hair cut short like a white man, and except when at work, wears a white shirt, fine black suit, and other clothing to match, and bears the sobriquet of ‘the dude Indian,’” reported Indian agent Stanton G. Fisher in 1890 of Billy George. A Boise Valley Shoshone, George is shown above with his wife Weetowsie and their children: Willie (on lap) and Harold.

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Leonard Collection, 145 –

The Edmos are a prominent ranching family at Fort Hall, having descended from Arimo, a Lemhi Shoshone leader (1806-96). About 10 percent of Wrensted’s photographs are of the Edmos. The Edmos controlled their images, though, by proudly wearing beaded Indian garments and not their everyday clothing as ranchers.

Shown here are Jack Edmo, with his wife Lizzie, Eugene (seated on his mother’s lap), Helen and Bessie (standing behind her sister), circa 1897. Jack is wearing moccasins with an American Flag beaded design, vest with cut-glass beads and metal rivets, quilled armbands and a traditional hairpipe and breastplate choker. Lizzie and Bessie wear traditional cloth dresses, while Helen’s velveteen dress is decorated with cowrie shells and she wears a hairpipe necklace.

This photograph was widely circulated. It was used in the 1979 exhibit “The American Image: Photographs from the National Archives” (and published in the book of the same name).

– All images on this page courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch, 75-SEI-93 –

Although unidentified, we can tell this is an early Wrensted photograph of an Indian cowboy as the wearer still has geometric rectangular designs, sometimes called a boxed-eye motif, on his breechcloth and chaps with the short fringe, which Sho-Ban elders say is traditional on their clothing. Transitional floral patterns began emerging in 1890-1950, which is when use of the boxed-eye motif began to decline.

– Courtesy U.S. National Archives –

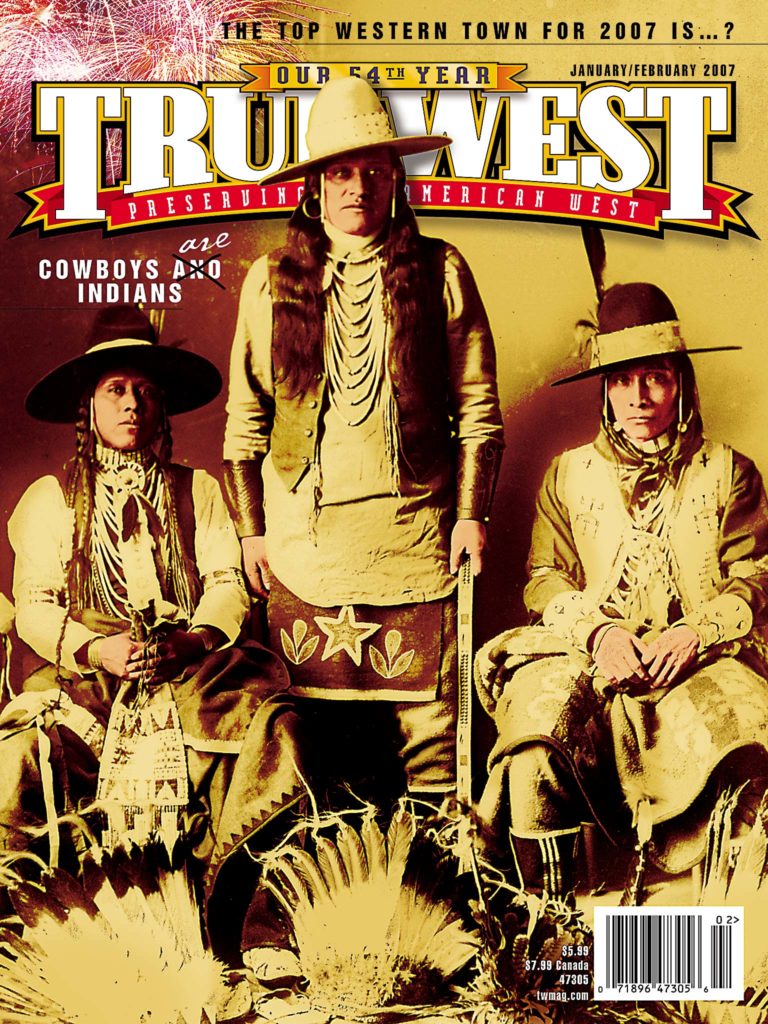

This beautiful display of traditional and reservation culture shows three cowboy Indians wearing their reservation hats and other ranching gear such as cuffs, vests, cloth shirts and pants and neckerchiefs, but also shows their traditional headdresses at their feet. This is a picture that truly reveals the interplay of culture evident at Fort Hall Reservation.

– Courtesy U.S. National Archives –

Cowboys were always known for chasing the ladies. This circa 1897 photograph of Lemhi Chief Tin Door makes us wonder who his object of affection may have been.

– Courtesy U.S. National Archives –

A photograph taken later than the others, as evident by the floral designs on the breechcloth. Since the earliest floral patterns were more abstract, this was probably taken toward the end of Wrensted’s career, as it is more realistic. The floral patterns are said to reflect patterns in the Sho-Ban’s environment such as wild mountain roses or morning glories. Nowadays, the “Shoshone Rose” motif is a recognized symbol at any Western powwow and rodeo.

– Courtesy U.S. National Archives –