The touring troupe would always remember that 1870s night in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, when Calamity Jane came to see them perform:

The touring troupe would always remember that 1870s night in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, when Calamity Jane came to see them perform:

“Calamity was dolled up for the occasion in corduroy suit and sombrero and appeared to be particularly vain of her green kid gloves,” wrote actor Charles Chapin. “As soon as she comfortably settled, she bit a chunk from a plug of tobacco and chewed as industriously as any miner throughout the evening. She and her escort [outlaw Arkansaw Bill] clapped their hands in noisy appreciation until Lady Isabel eloped with Sir Francis and then Calamity showed her disapproval of the erring wife’s conduct by marching down to the footlights and squirting a stream of tobacco juice over Lady Isabel’s pink satin evening gown. There came very near being a rough house. Trouble was avoided by the lady desperado tossing a handful of gold coin over the footlights to pay for the gown she had so ruthlessly disgraced. Throughout the remainder of the performance she chewed her cud in courteous silence.”

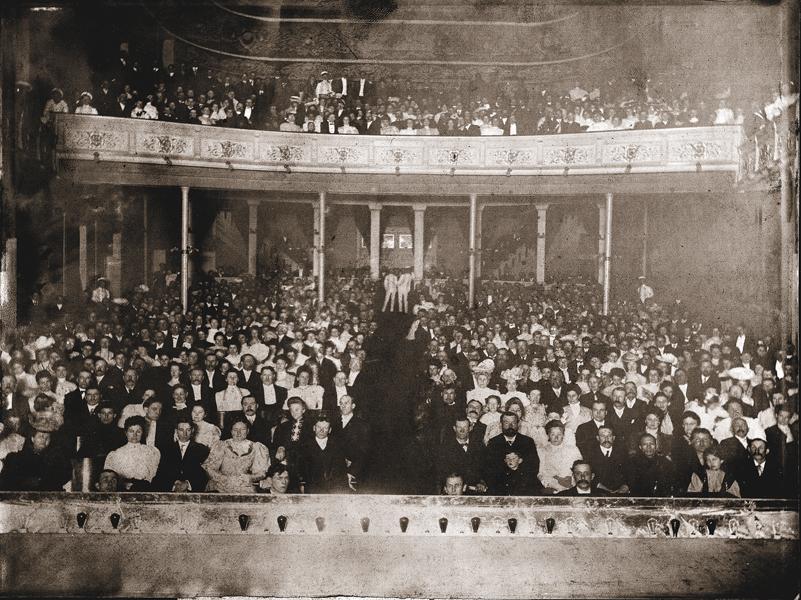

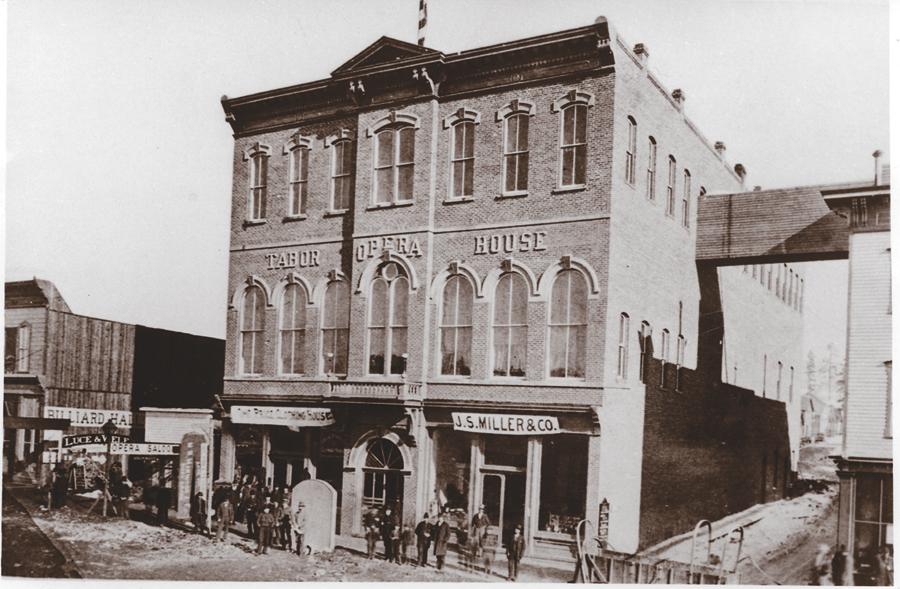

Nearly every Western town had an opera house—people preferred that name to ‘theatre’ because it sounded more cosmopolitan. To attract settlers, a town had to be viewed as “progressive,” and no place without an opera house could lay claim to that distinction. The theatres ranked with general stores and schools as the important buildings in town.

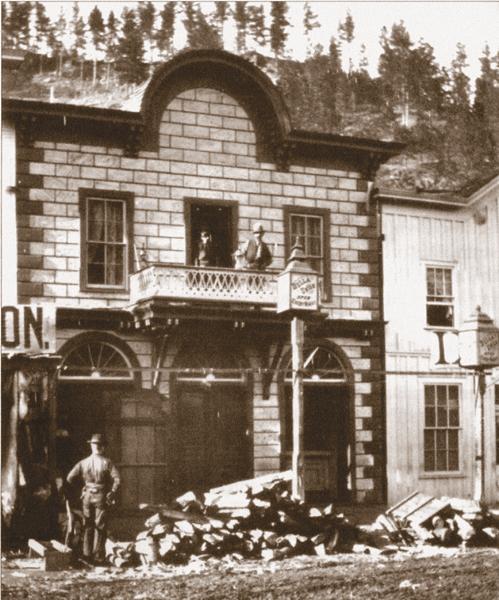

Deadwood loved its theatres more than most. It never held fewer than three and sometimes up to eight. Twice after the town burned, citizens rebuilt opera houses before homes. “The pioneer immigrants of Deadwood hungered for entertainment of any kind and were ready to pay the price, often exorbitant, for an evening’s diversion,” notes Deadwood historian Lawrence Stine.

Miners took over $4,000,000 worth of gold from Deadwood Gulch between 1876-79, and the two theatre men who profited most were Jack Langrishe and Albert Ellis Swearengen.

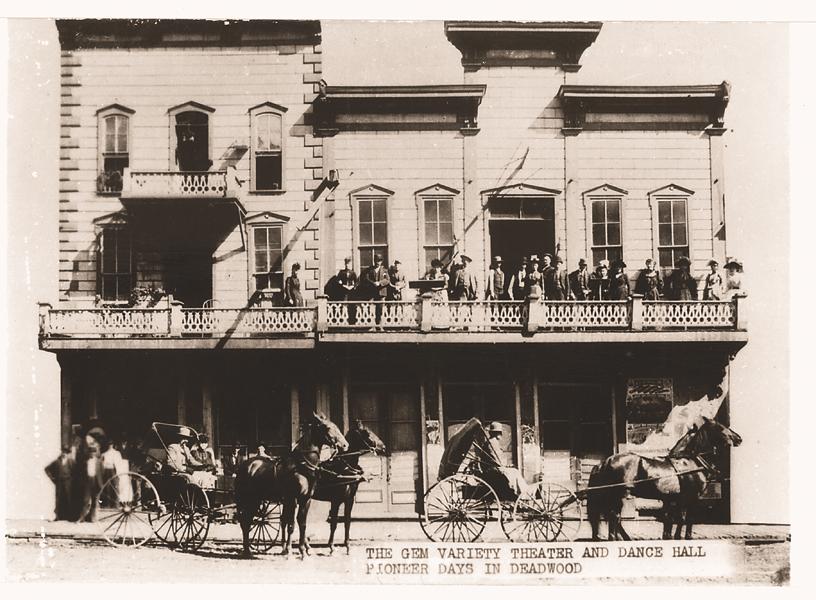

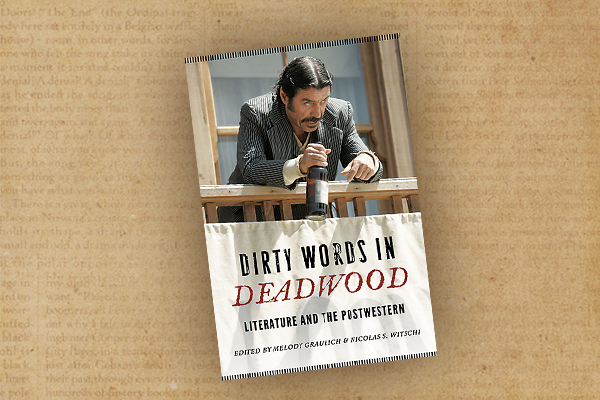

Despite their common profession, the two could hardly have been more different. Langrishe was a classically trained actor who embodied all the good frontier theatre offered: class, intelligence and entertainment. Swearengen, in contrast, called his establishment the Gem Variety Theater to cover a myriad of sins, including prostitution, alcohol, organized theft, gambling and violence.

As their contemporary Estelline Bennett wrote in Old Deadwood Days: “Deadwood had more places of amusement than any other town of its size in the country. But it is these two sharply contrasted theaters, the Gem and the Langrishe, that are remembered best.”

Jack Langrishe:?The traveling theatre man

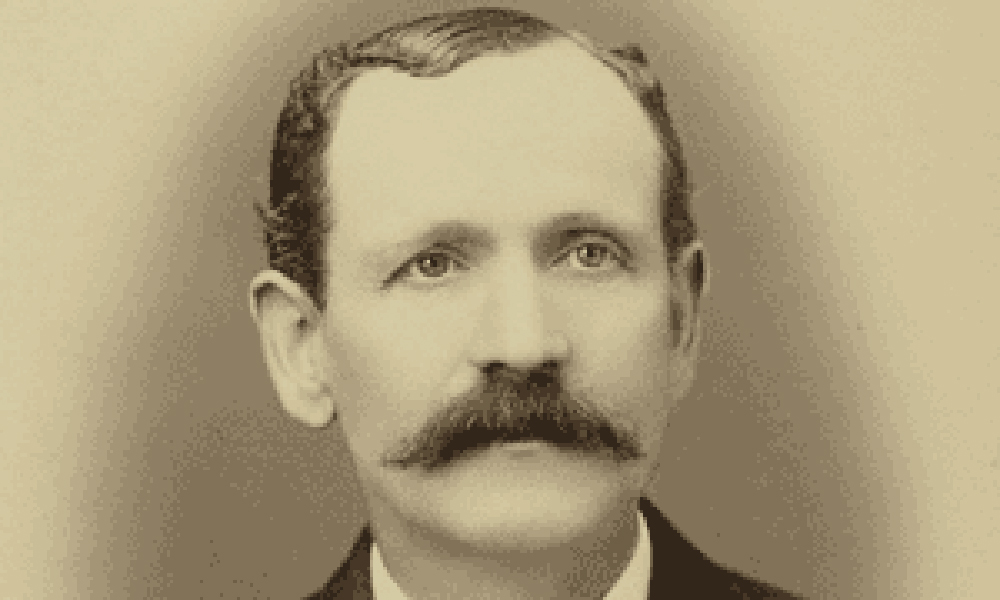

John S. “Jack” Langrishe was born in Dublin, Ireland, September 24, 1829, and was already a child actor when he emigrated to America in 1845. In 1850, he married Jeanette Allen (great-granddaughter of Revolutionary hero, Ethan Allen) who was called “a clever actress in her own right.”

The Langrishes yearned for the freedom of the American West and organized a troupe that toured from Mexico to San Francisco. “Jack Langrishe and his wife are the only actors in the history of the theater who, given the choice, preferred the mountains of the West to Broadway,” Bennett wrote. “They were known wherever men dug gold as the ‘mining-camp players.’ Simultaneously with every good discovery, it was said, Jack Langrishe appeared with a theater under his arm—a real theater with no dance hall or bar attached, a house of clean, clever comedy, melodrama and tragedy, to which men took their families, and whose doors never opened on Sunday. He built more theaters on the frontier than any other man who ever lived.”

Langrishe earned up to $30,000 in one summer season, but he always struggled with the economics of acting. Paying for salaries, costumes and scenery, as well as renting or owning theatres, led to a string of bankruptcies. In fact, he fled to Deadwood to escape creditors in Cheyenne, Wyoming. He was unable to pay for transporting his equipment, so he came only with his fellow actors. The residents welcomed Langrishe with open arms and open pocketbooks. Citizens paid to put the actors up in a hotel and financed a temporary theatre. Langrishe performed Deadwood’s first legitimate play, The Banker’s Daughter, on July 22, 1876. Tickets sold for $1.50 for the first 10 rows and a dollar for the rest.

After a rainstorm destroyed his makeshift theatre, Langrishe rented the Bella Union Opera House for his performances, while his partner, James McDaniel, rebuilt the theatre. “When the Theatre opened, amid the pop of wine bottles and the blare of a brass band, the crowd was estimated at 1,200,” reported the local newspaper. That was nearly half of Deadwood’s 3,000 citizens.

The Bella Union was also famous for another show—it was used as a courtroom for the August 5, 1876, trial of Jack McCall. Bennett wrote of Langrishe, “Early in ’76 he came to Deadwood and for a short time leased the Bella Union variety theater giving it, during his tenancy, a strange new character that must have astonished its log walls. During his short lease Wild Bill [Hickok] was killed by Jack McCall in the Number Ten saloon next door, and Langrishe gave the use of the theater for the rump court that tried and acquitted McCall.”

Langrishe’s troupe performed dramas from Hamlet to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, though the actors specialized in comedy. But they also faced some unique challenges. Being an illegal settlement in Indian Territory, Deadwood was not on the railroad line and there wasn’t a stop within 200 miles. While other towns’ opera houses stayed fresh with the arrival of new troupes via the trains, Deadwood was locked out. So Langrishe’s troupe was compelled to learn hundreds of plays, some written by Langrishe, and it wasn’t unusual for the actors to perform six different plays in a week.

The showman’s efforts paid off, at least temporarily. In 1878, Langrishe built a new theatre in Deadwood and two more in surrounding towns. But his fortunes burned up in the Great Deadwood Fire of 1879. Langrishe was one of 2,000 left homeless, and his theatre was among the 300 buildings that were destroyed.

At first, he took the devastation with characteristic humor. Standing over the smoking ash that had been his theatre, Langrishe told fellow actor, Jimmy Martin: “I guess we’ll have to put out the ‘standing room only’ sign, Jimmy, there isn’t a seat left to sit on in the house.”

He was forced to tour again to raise money, saying he hoped to return and rebuild, but it never happened. As The Black Hills Daily Times reported, “He was rumored to be piling up another of the fortunes he habitually made and lost.” Langrishe eventually settled in Idaho, where he was elected to its first state legislature. He died in 1895 and was buried in Kellogg, Idaho. Jeanette was with him to the end. She died in August 1900 in Wardner, less than a mile from Kellogg, Idaho historian Charles Lauterbach says. It is believed Jeannette was laid to rest next to her husband, although no marker or burial records have proven this true.

Al Swearengen’s hurdy-gurdy house

The Great Deadwood Fire destroyed the just and unjust alike, for along with the Langrishe Theatre, it also leveled Al Swearengen’s “notorious den of iniquity”—at first, called a “hurdy-gurdy” house, but later it was known as the Gem Theater.

Bennett would remember that as a child, she’d heard the Gem brass band luring customers and she desperately wanted to answer the call. But her father, Deadwood’s first judge, told her “Nice people like us don’t go to the Gem.”

Bennett recalls Swearengen as being “dark and low-browed,” who “suggested in face and character the old-time villain of melodrama. Yet his years of prosperity were long and full. He was said to have handled more money than any other man in Deadwood. An ordinary night’s business was five thousand dollars. It was known to run as high as ten thousand.”

The Gem ruled over “the badlands”—Deadwood’s red light district. The theatre offered the best saloons, the most gambling tables and the best-looking girls. For stage shows, it offered legitimate theatre, dancing girls, vaudeville, burlesque, trained dogs, magicians and boxing matches. The music, like everything else, was simply a means to make money. After each song, the caller sang out, “All promenade to the bar, and make room for the ladies.”

Swearengen earned most of his cash from alcohol. He bought whiskey for $1.65 a bottle and sold it in shots for over $64. Then came profits from drunken customers. Men often regretted what they did “while on the jag.” Losing money at gambling tables was one thing, but the most profitable Gem swindle was called “rustling the boxes”—girls lured customers to theatre boxes before closing the curtains to hide a variety of sins. Men seldom walked out with any money remaining. One poor guy, known only as Hermann A., came to Deadwood with $300 in his pocket, which was empty when he was found the next morning hanging from a tree. The coroner listed it as a suicide.

But most victims claimed by the Gem were its own “soiled doves.” “Smith, the undertaker, was appalled by the number of girls of the Gem who had committed suicide,” Bennett recalled. “Many a case that had been pneumonia or mountain fever in the papers was laudanum or a bullet in the undertaker’s record. Now and then a murder that could not be hushed focused the town’s attention, and inconsequent shootings were of common occurrence. No one paid much attention. It was an accepted phase of mining camp life.”

Whether their tenure ended with death or some other trouble, girls rarely worked the Gem for more than a few years, and Swearengen was continually pressed to find, as he put it, “fresh talent.” He routinely traveled east “to secure actors,” and once he lured them all the way out to Deadwood, he bullied and beat the women into submission. Nor could they seek help from the law. When a woman called Swede Lena prosecuted Swearengen for beating her, he was exonerated—as he always was—on the defense that “she didn’t conform to the rules of the house.”

One talent scouting trip proved memorable because it marked a rare time when Swearengen didn’t get his way. He had traveled to Chicago and advertised for young women to go West at a salary of $15 for “hotel work generally.” Eleven girls answered the ad. When their stagecoach arrived in Deadwood, men gathered to ogle the new recruits, but several respectable citizens took the girls aside to set them wise. Five girls fled, getting protection (and money for a ticket home) from Deadwood’s decent citizens.

Another girl who escaped Swearengen with outside help was the famous singer Inez Sexton, formerly of Paris’ Can-Can Review. When she refused to sell more than her voice, a benefit raised the money to help her get out of town. Bennett explains why:

“Deadwood was a wide-open, careless, happy-go-lucky town. The Gem Theater, the dance halls, saloons and gambling houses were its very life. But to throw a woman unwillingly into the ways of the badlands was entirely outside Deadwood’s code.”

Despite his reputation, Swearengen always found enough women to stock the Gem. When he opened his new, improved Gem in 1877, miner George Stokes was there, and he remembered: “A dozen women of the underworld, Mollie Johnson and Cis Clinton among the most notable, occupied boxes at the Gem. That first night Calamity Jane, under a 10-gallon Stetson with a cowman’s purple handkerchief around her neck, danced with everybody and promenaded to the bar, as was the custom, after every dance.”

The Deadwood fire destroyed the Gem, but Swearengen possessed enough money to see destruction as opportunity. He rebuilt the theatre in brick, expanded the Gem and squeezed out his competitors.

Swearengen’s amazing success ended in 1890 when the railroad arrived. The city became more civilized, and long-overlooked laws regulating alcohol, prostitution and gambling were enforced. By 1902, he had lost whatever he had left. He died a common tramp, killed by a locomotive in the rail yards of Denver as he tried to steal a ride. He was buried in a potters field.

That was the closing scene of the final act of Deadwood’s colorful theatres.

Visit www.truewestmagazine.com for the origin of the phrase “tripped the light fantastic.”

Historian Ried Holien is the South Dakota author of

Skeletons of the Prairie and has also served as advisor

to four state historical societies.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Adams Museum and House –

– Courtesy Adams Museum and House –

– Courtesy Ried Holien –

– Courtesy State Historical Society of Colorado –