On September 11, 1857, 120 men, women and children—pioneers from Arkansas headed for California—were massacred after being promised safe passage through a Southern Utah valley known as Mountain Meadows.

On September 11, 1857, 120 men, women and children—pioneers from Arkansas headed for California—were massacred after being promised safe passage through a Southern Utah valley known as Mountain Meadows.

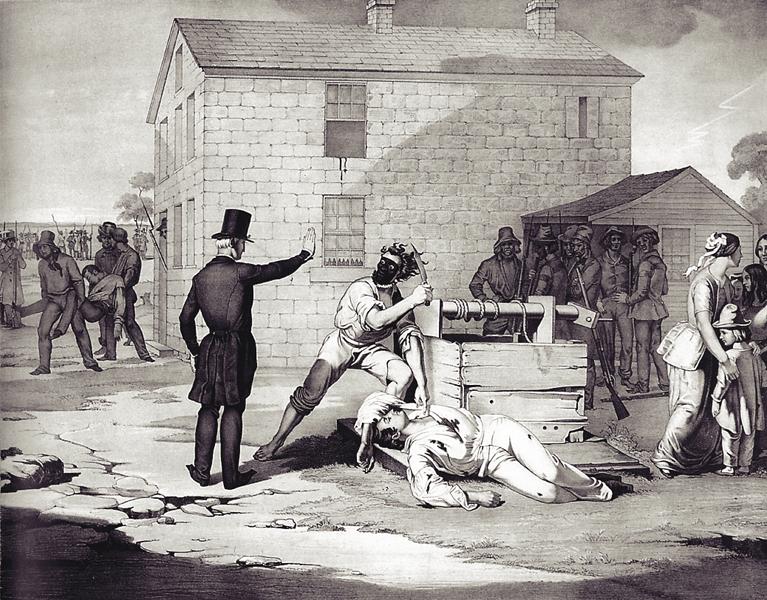

They were murdered by a small Mormon militia and its Indian allies in a horrible ploy: after a four-day gun battle with their attackers, the pioneers accepted a truce that turned out to be a deadly lie. They were clubbed, stabbed or shot at point-blank range, then stripped and left to be scavenged by wolves and buzzards. The only ones spared were 17 children under the age of eight, who were taken in by local Mormon families, and would later testify they saw their parents’ clothes and jewels being worn by locals.

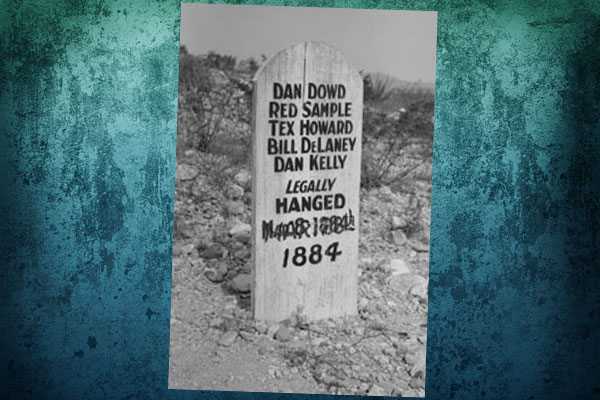

The nation was and remains horrified by what happened at Mountain Meadows. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has steadfastly denied responsibility. At first, it blamed Indians; later, it claimed a rogue church official was responsible—and after two trials, Mormon militia leader John Lee was hanged in 1877 for the killings.

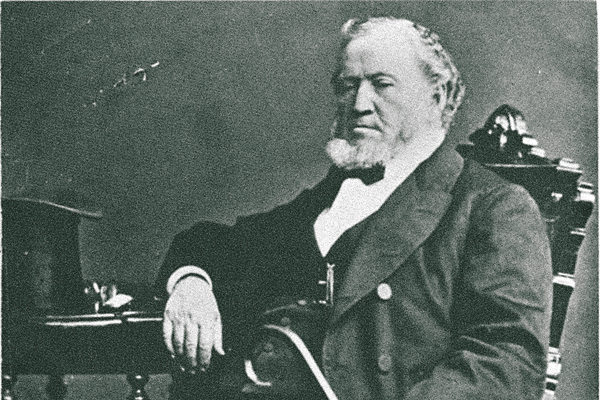

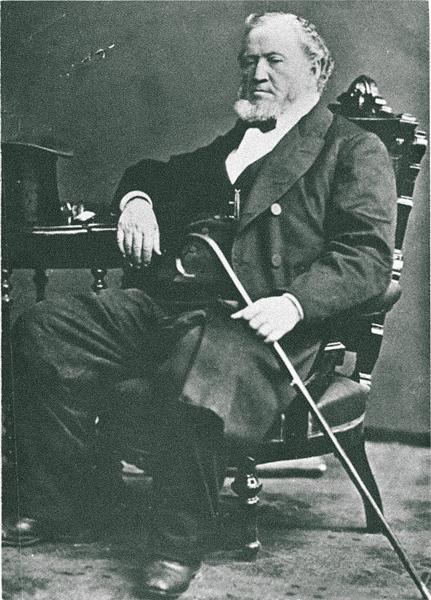

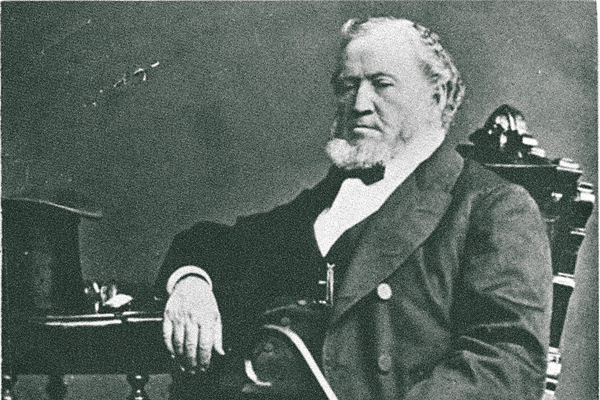

But now, a new book, which has been a bestseller in Utah since it appeared last summer, claims the massacre was ordered by Mormon Prophet Brigham Young. Anxiously awaited is a book due to be published in 2004 by three Mormon church historians that will exonerate Young.

True West asked the authors of both books to lay out their claims. Will Bagley, a history columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune, is the author of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows published by the University of Oklahoma Press. Ron Walker is one of the three Mormon historians writing the upcoming rebuttal to be published by Oxford University Press.

Their face-off begins.

Brigham Young Did It.

By Will Bagley

There are two ways to interpret the evidence about who ordered the brutal murder of 120 men, women and children at a remote Utah oasis on the road to California on September 11, 1857. Fifty-three years ago Juanita Brooks’ classic study, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, concluded the crime was the result of one unfortunate circumstance after another. (She also established “from the most impeccable Mormon sources” that Brigham Young had obstructed a murder investigation for 18 years, which made him guilty of felony murder.)

The second explanation is that the massacre was a calculated act of vengeance.

After five years researching and writing about this horrific atrocity, I doubted I’d ever find a definitive answer to the question, “Did Brigham Young order the murders at Mountain Meadows?”

I was wrong.

To my surprise, I found evidence that convinced me beyond a shadow of a doubt that Brigham Young issued orders (probably verbal) to kill everyone in the Fancher party except those of “innocent blood”—children under eight years of age—to fulfill his sacred vow to “avenge the blood of the prophets” Joseph and Hyrum Smith, and more specifically, Apostle Parley P. Pratt. As one of John D. Lee’s wives put it, “The Mormons were so insulted and indignant over the death or murder of Pratt that they Raked untold Vengeance on the poor Emigrants.”

When I began writing about the massacre, I realized trying to “prove” anything about this appalling crime would prove only that I was an idiot. The evidence has been so corrupted—suppressed, destroyed, and fabricated—it’s hard to determine the date the murders took place, let alone trace all the ins and outs of the conspiracy behind the crime. Writing a polemic trying to blame Brigham Young would be self-defeating, just as writing an apologia to clear his skirts would ultimately have to justify murder. Instead I tried to tell the story as honestly and accurately as possible and let readers make up their own minds about who ordered the slaughter of more than 80 women and children—and why.

Apparently I succeeded, since critics in the employ of the LDS Church claim I don’t “prove” Brigham Young ordered the murders. People make what they want of the facts in my book, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, but for most readers, the evidence about who ordered the massacre is overwhelming.

As any attorney knows, the problem with a guilty client is he acts guilty, and after the massacre Brigham Young never behaved like an innocent man. Young’s fiery discourses calling for blood and vengeance, his encouragement of Indian attacks on wagon trains and the lies he told to cover up the crime all show he was intimately involved in fomenting a vicious act of vengeance.

He said he did it.

Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War, Brigham Young and his entourage visited Mountain Meadows for the first time since 1857. He stopped at the cairn the U.S. Army’s First Dragoons had raised in 1859 over the grave of the emigrants whose scattered bones they had collected and buried. Young read the Bible verse the soldiers had inscribed on a cedar cross atop the monument: “Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord.”

“It should read,” he said, “‘Vengeance is mine, and I have taken a little.’” Young then directed the desecration of the grave. “Within five minutes,” recalled massacre participant Dudley Leavitt, “not one stone stood upon another.”

A few days later Young justified the massacre as a necessary act of righteous vengeance. “The company that was used up at the Mountain Meadowes” included the fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters “& connections” of the men who murdered the prophets, he told John D. Lee, and “they Merited their fate.” The only thing that ever troubled Young “was the lives of the Women & children, but that under the circumstances [it] could not be avoided.”

“But,” I can hear Mormon historians object, “this is purely circumstantial evidence Young actually ordered the killings.” Could be, but it’s no more circumstantial than the evidence O.J. Simpson murdered his wife.

Why did Brigham Young allegedly send a message telling Southern Utahns NOT to kill the emigrants unless he was countermanding previous orders? Why didn’t he use his powers as territorial governor to hunt down the men who committed this despicable crime? Why did he do nothing to return the stolen property of the 17 surviving orphans? Why did he threaten honest men who called for justice in the matter? Why did he shield the murderers and allow the church’s newspaper to blame the crime on the Paiutes for a dozen years after Jacob Hamblin told him Mormons were involved? And why does the Deseret News continue lying about Mountain Meadows to this day?

Finally, why has so much evidence been destroyed or purged from Mormon archives, and why has so much evidence been suppressed?

There’s one answer to all these questions: Brigham Young ordered the murders as a righteous act of vengeance.

Learning how Eleanor McLean Pratt got to Salt Lake City convinced me Brigham Young “did it.” The 12th Mrs. Pratt had buried her polygamous husband Parley in Arkansas the previous May, and she was obsessed with exacting vengeance from his murderers. She believed God’s “legions” would “hunt them down in every land & place.” With help from Mormon apostles in Missouri, Eleanor arrived in Utah on July 23, 1857, where she allegedly charged that men in the Fancher party had helped her first husband murder Apostle Pratt. She demanded Mormon authorities listen to “the cry of his blood” and take swift vengeance against the Fancher train, which had left Arkansas long before Pratt was killed.

How did the widow Pratt cross 1,500 dusty miles in a mere 21 days?

That question stumped me for years, and like many other Mormon mysteries the clues have been carefully purged from the records of Utah’s past. When I learned that Orrin Porter Rockwell, the notorious Mormon lawman and “Danite,” had rushed Mrs. Pratt across the plains in record time, I knew what happened at Mountain Meadows.

Why? The great historian Harold Schindler spent 40 years learning everything there was to know about Orrin Porter Rockwell, Man of God/Son of Thunder (the title of his definitive biography). Hiding Rockwell’s role in expressing Eleanor to Utah from my late friend Hal was evidence that had been carefully suppressed. And “the suppressing of evidence,” Andrew Hamilton said in 1735, “ought always be taken for the best evidence.”

Brigham Young did it.

No He Didn’t.

By Ron Walker

Americans enjoy a good mystery, and they like conspiracies. They are also fascinated by stories of murder and especially murder on a grand scale. It’s no coincidence, then, that pulp fiction and Hollywood have used these ingredients—mystery, conspiracy and mass murder—for years. So do some authors who’ve written about the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

There is a logic to this. It creates a sensation and sells books. But it’s not a formula for good history.

Good history must be based on facts. Stubborn facts. Not theories. Not circumstantial evidence. Not historical conspiracies created by authors speculating about the past.

The following are a few facts necessary for an understanding of this terrible event in Western and Mormon history.

Brigham Young tried to stop the massacre.

“In regard to emigrating trains arriving and passing through our settlements,” he wrote in a letter designed to restore calm in Southern Utah, “We must not interfere with them.” These clear and difficult-to-misread words were rushed to Cedar City after Young received an express from local setters there telling him of pending trouble. Tragically, Young’s letter arrived two days after the massacre, despite one of the epic rides in Western history. James Haslam, who rode the 500-mile circuit in six days, recalled, Young “told me [when riding back south] . . . not to spare horseflesh.” He didn’t.

Copies of Young’s letter exist both in rough draft and final draft form. The latter is filed in sequential order in Young’s well-preserved and bound letter books. Witnesses later testified about Haslam’s dramatic arrival in Salt Lake City, the writing of the letter and its dispatch South. In short, Young’s letter must be taken at face value: It was a determined, almost frantic, attempt to stop the massacre.

No credible evidence exists that Young wanted the massacre.

Of course, anti-Young historians say otherwise. For motives, they point to the persecution of the Mormon people and to the earlier killing of Mormon leaders Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Adding fuel to Mormon rage, they argue, was the killing, a few months before the massacre, of Apostle Parley P. Pratt. Pratt had been murdered in Arkansas, where the Baker-Fancher party had its origin. Wouldn’t these events have kindled Young’s anger and led him to seek revenge? Critics assume, yes.

But history is not assumption. The facts are these: Young spoke out against revenge killings. Justice for his people’s wrongs was heaven’s responsibility, not his, he said. Nor did Pratt’s death stir blood lust. “The seeing of our faithful Elders slaughtered in cold blood,” he wrote after his friend’s death, is “at times almost to[o] grevious to be borne, but as the Spirit within me whispers, peace be still.” This advice was never changed.

Logically, the idea of ordering a massacre as 2,500 U.S. troops marched upon Salt Lake City is absurd. Young was too clever—and too religiously devout—to have destroyed the emigrants and thus irreparably harm the reputation of his people. The crisis of the Utah War demanded that he husband moral authority and public opinion.

Young was not complicit in planning or executing the massacre.

With no additional evidence, some historians have pointed to a Native American council held in Salt Lake City on September 1, 1857. The council sought to create a Mormon-Indian alliance, and to make such an arrangement attractive to the Indians, Young allegedly told them that he would no longer stop them from stealing emigrant cattle on the California Trail.

While this Indian council is important and requires extended scholarly discussion, this much can be said: No evidence suggests the council’s focus was the Baker-Fancher party, much less its destruction. No evidence exists that the Indians at the council agreed to attack. Finally, it is also a matter of historical record that none of the Indian leaders at the Salt Lake council were later at Mountain Meadows, except the Southern Ute leader, Ammon, who tried to prevent the massacre.

Evidence exculpates Young.

Because the historical past will always be opaque, historians must seek the weight of evidence, and in this case, the preponderance suggests Young’s innocence. Particularly telling is the testimony of those who did the killing at the Meadows. These men later insisted that no orders had come from Salt Lake City, and this testimony included that given by those who in later life left Utah and Mormonism. Some testimony came in private interviews when there was no motive to lie.

Likewise, John D. Lee, the only man convicted of the murders, was repeatedly offered leniency in exchange for incriminating Young—the last offer was made just moments before his execution. Despite a growing bitterness toward his former mentor, Lee refused. “Matters have & are being delayed with design of Cohearce [to coerce] me to Make a statement beyond what I know,” he wrote in his diary. But “I am determined by the help of God never to bear false witness against My Neighbour.” Later, he complained that those who questioned him wanted lies, not truth. Rather than provide them with what they wanted, Lee “chose to die like a man then [than] to live a villain.”

The events at Mountain Meadows do not suggest a conspiracy, and certainly none involving Young.

While several reasons for this statement may be suggested, most persuasive is the ebb and flow of the local decision-making during the weeklong event. In this period, militia leaders at Cedar City and at Mountain Meadows changed their minds several times whether the killing should go forward. They were reacting to events as they took place. Even on the day of the slaughter, couriers were reportedly hurrying from Cedar City—30 miles to the east—to call it off. In short, the massacre is best explained by cascading local events in a setting of extreme excitement and fear. When it was over, men quarreled over responsibility, and many vowed that no one should ever know of their deadly work, including, presumably, Brigham Young.

Young was not a man of violence.

While the church leader’s temper and strong words at the pulpit earned him a reputation for coercion, in truth, those who knew him best often spoke of his caution and his abhorrence of bloodshed. Militia orders to the Mormon army carried Young’s words on the reverse: “Shed no blood.”

“When the books are opened in the day of judgment,” declared an associate who was at his side in 1857, “these things will be proven to heaven and earth.”

The Mountain Meadows Massacre was a horrible atrocity, and the conduct of some Mormons involved in it was deplorable: strong words from the Tabernacle pulpit, Saints seeking vengeance because of their past persecution, Young’s risky Native American alliance, senseless acts by some local Mormon leaders, Utah’s troubling episodes of extralegal violence and most awful, the terrible killing at Mountain Meadows. But we only make the tragedy worse by saying that it was something other than what it was—by trying to fit events into a pre-conceived theory of conspiracy. That admonition includes charging Brigham Young with crimes that he did not commit.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –