Scratch the reputation of a legendary killer of the Old West, and you’ll find a layer of myth.

Scratch the reputation of a legendary killer of the Old West, and you’ll find a layer of myth.

Scratch that layer, and you’ll likely find another one, and another one beneath that, ad infinitum. By the way, that’s Latin, dahlin’ and a term with which John Henry “Doc” Holliday would have been quite familiar.

The first layer of Doc Holliday’s myth was the infamous water hole shooting incident. The earliest written mention comes from Bat Masterson’s profile of Doc written for a 1907 edition of Human Life magazine. Here’s his account:

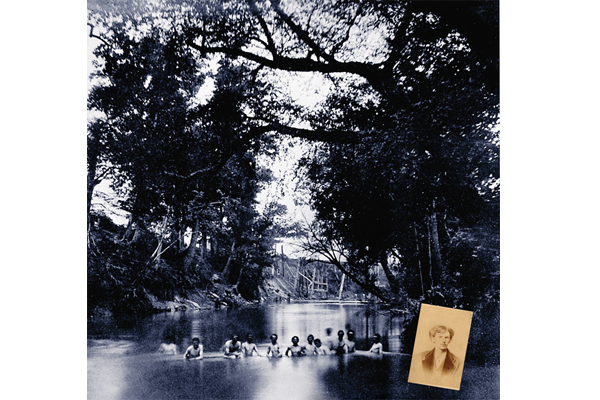

“The indiscriminate killing of some Negroes in the little Georgia village in which he lived was what first caused him to leave his home. The trouble came about in rather an unexpected manner one Sunday afternoon … there flowed a small river in which the white boys of the village, as well as the black ones, used to go swimming together. The white boys finally decided that the Negroes would have to find a swimming place elsewhere and notified them to that effect … which they promptly refused to do and told the whites that if they didn’t like existing conditions, that they themselves would have to hunt up a new swimming hole.

“As might have been expected in those days in the South, the defiant attitude taken by the Negroes caused the white boys to instantly go upon the war path…. Holliday appeared on the river bank with a double-barreled shotgun in his hands and, pointing in the direction of the swimmers, ordered them from the river. ‘Get out, and be quick about it,’ was the preemptory command…. Holliday waited until he got a bunch of them together, and then turned loose with both barrels, killing two outright, and wounding several others.

“The shooting, as a matter of course, was entirely unjustifiable, as the Negroes were on the run when killed, but the authorities evidently thought otherwise, for nothing was ever done about the matter…. His family, however, thought it would be best for him to go away for a while and allow the thing to die out; so he accordingly pulled up stakes and went to Dallas, Texas.”

If Masterson is correct, this would place the shooting in 1873, when Doc was 22—if the shooting happened at all. Several errors can be found in Masterson’s story, which leads to the historical detective’s first question, “Who wrote it?” The popular speculation is that his friend, the flamboyant Hearst Publications feature writer and editor, Alfred Henry Lewis (who was also known for years under the name Dan Quin), actually wrote Masterson’s profiles.

Eleven years ago while working on a story on Doc for The Oxford American, I consulted Jack DeMattos, who annotated and illustrated the 1982 edition of Bat’s collected Human Life pieces. “A simple comparison of their styles,” DeMattos told me, “indicates that Lewis was far more verbose. Bat was more direct.” A brief glance at the plain style of Bat’s boxing and horse racing journalism as well as his letters to President Theodore Roosevelt do reveal a sharp contrast to the flighty rhetorical flourishes of Lewis’ novels. That doesn’t mean Lewis’ influence as an editor on the stories wasn’t profound; it also doesn’t mean that he wasn’t capable of adding a novelistic touch or two.

For instance, in the Human Life profile of Holliday we find the famous sentence, “Damon did no more for Pythias than Holliday did for Wyatt Earp.” If one were searching for a trace of Lewis’ influence, passages with classical allusions would be prime candidates. My suspicion is that Masterson wouldn’t have known Damon and Pythias from Matt Damon and Ben Affleck.

Lewis did, after all, have a firsthand source on Holliday besides Bat. In the 1890s, he became friends with the legendary lady gambler, Lottie Deno, the “Queen of Hearts,” and her husband, Frank Thurmond, who were living at the time in Deming, New Mexico; he mined both of them for material for his Wolfville novels, in which Doc appears as a character.

At any rate, some glaring errors in the Human Life profiles appear more attributable to an editor than to the writer. For instance, the chapter on Earp states that Wyatt served in an Iowa regiment during the last three years of the Civil War, which would mean that he would have enlisted when he was 14. This is almost certainly a mistake made by Lewis, not Masterson, possibly while taking notes from Masterson.

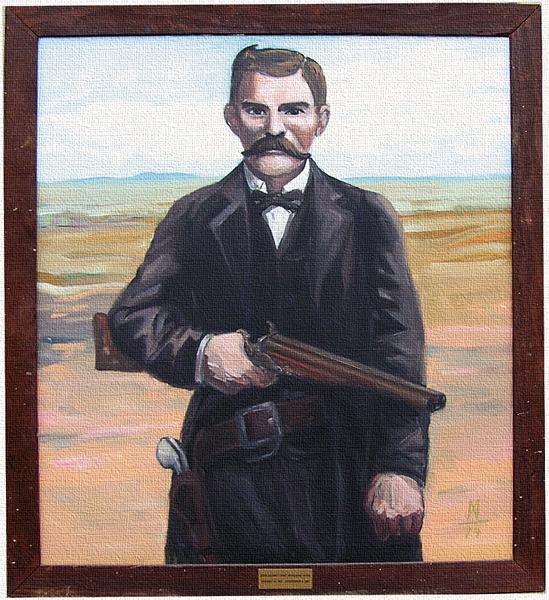

Some descriptions of Holliday are just as puzzling. Why, for instance, would a frail young man be carrying a double-barreled shotgun? In a photograph taken of John Henry when he was in dental college in Philadelphia, he looks to be no more than perhaps 130 pounds. Wyatt Earp claimed that until Virgil handed Doc a shotgun before the street fight in Tombstone, he had never seen one in his hands. Doc would probably have laughed at the oil portrait by a Japanese artist that hangs in the Lowndes County Museum in Valdosta, Georgia, depicting Doc holding a twin-barreled scattergun.

Another quirky claim by Masterson is when he states, that while “Holliday never boasted about the killing of the Negroes down in Georgia, he was nevertheless regarded by his new-made Texas acquaintances who knew about the occurrence as a man with a record; and a man with a record of having killed someone in those days, even though the victim was only a ‘nigger,’ was looked upon as something more than the ordinary mortal.” None of this rings true. Texas in 1873 was still a rugged enough place that the shooting of an unarmed black youth three states away would hardly have bolstered one’s reputation as a hard case. Anyway, there is no evidence that Holliday’s new Texas acquaintances had ever heard of any such deed or indeed heard of Doc Holliday in any capacity except that of a competent dentist.

Which leads to an even more intriguing question. If, as Masterson maintains in Human Life, Doc never boasted about the killings, how exactly did Masterson find out about them? No mention of the water hole shooting has been found in a Texas, Georgia or Kansas newspaper (nor, lest we forget, any other paper). If any of Doc’s contemporaries other than Masterson knew of it, they didn’t mention it. The incident isn’t mentioned in any version of Wyatt’s memoirs or interviews or in letters to Stuart Lake or anyone else. The memoirs of his wife, Josephine Marcus, also make no reference to it.

Wyatt and Josephine were well disposed towards Doc and perhaps not likely to repeat any story that would cast him in a bad light, but surely Billy Breakenridge would have been happy to discredit Holliday, and the water hole incident is not mentioned in his memoir, Helldorado. Tombstone Epitaph editor and mayor John Clum and Wells Fargo informant Fred Dodge were, like Masterson, friends of Wyatt Earp, but, like Masterson, they both disliked Holliday. Dodge even went so far as to claim that Doc was involved in the Benson stage robbery in March 1881. But neither Clum nor Dodge ever mentioned the water hole shooting.

During the 1940s-60s, the water hole incident became a staple of any magazine or Sunday supplement newspaper article about Doc and was taken as gospel by popular Western historians such as James D. Horan. All sources in that period trace back to Masterson’s article; not one cites another source.

Twists to the Story

In their 1973 pamphlet, “In Search of the Hollidays,” two of Doc’s descendants, Albert S. Pendleton and Susan McKey Thomas, relate a version slightly different from Masterson’s. In the story handed down to them, John Henry was riding in a buggy with his Uncle Thomas when they came upon some black youths—there are no white boys mentioned—swimming in a backwater of the Withlacoochee River. Apparently the area had been cleared to be used for a family swimming hole. John Henry was outraged and pulled a pistol—a weapon he would have been much more comfortable with than a shotgun—and began shooting over the boys’ heads. Uncle Thomas, the only one who ever said he witnessed the shooting, never claimed that anyone was shot. If this is an accurate account of what happened, one wonders why it was remembered at all.

In his superb new biography, Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend, Gary Roberts has unearthed yet more stories about the alleged incident. One, passed down by family members of John Henry’s father’s second wife, is that “there were some words that Doc allegedly killed one of the Black youths with a gun.” Still another, from the youngest of Uncle Tom’s children, quoted by Roberts, is that “Papa told me Doc shot over their heads”—again, the only person who claimed to be a witness maintained that no one was hurt.

In a drastically different recounting uncovered by Roberts in a 1931 edition of the Valdosta Times, “several Negroes had been throwing mud and stirring it up so that it was unfit to swim in. Holliday began scolding the negroes and one of them made threatening remarks back to them. John immediately got his buggy whip and proceeded to punish this hard-boiled negro. The negro fled and returned in a few minutes with a shotgun. He shot once and sprinkled Holliday with small bird shots. Holliday promptly got his pistol and pursued the fleeing negroes. When the negro who had shot at him saw that the youth meant business, he took to his heels and could not be caught.”

One hardly knows what to make of this version. Doc was known to have been hit by just a single bullet during his entire lifetime, a shot from Frank McLaury during the street fight in Tombstone that nicked his hip. But if the Valdosta Times story is true, a black youth—who happened to be armed with a shotgun (albeit one loaded with only bird pellets) and with the temerity to use it on a white man, in Georgia, in 1873—shot Doc eight years before Frank McLaury.

What are we to make of all these retellings of the story? Nearly all of them, when scrutinized, seem to raise more questions than they answer. Basically, they all fit into two categories: in the first, no one is seriously hurt, and in the second, one or more black youths are murdered. If those that fit under the first heading are true, we are entitled to ask, why was the story worth remembering? And if those that come under the second heading are true, why is there no evidence? The family accounts, some of which fall under both headings, are intriguing, but in a court of law they would be disregarded as “hearsay.” Perhaps not coincidentally, all recorded accounts, including the 1931 Valdosta newspaper story and the Pendleton-McKey pamphlet, come well after the Masterson story was published. No direct evidence of the shooting is identified—say, a letter from someone in the 1870s, or a diary or memoir from the 1880s or 1890s—that predates Masterson’s Human Life story.

Roberts points out that the Valdosta papers for 1873 are incomplete and the criminal records for that period in Lowndes County are lost. But even so, if the shootings were serious enough to compel Doc to flee Georgia, surely there would have been some mention in a newspaper at a later date. For that matter, if the story was well known, why wasn’t it mentioned in Doc’s obituaries in papers not only in Georgia but out west?

Which leads, perhaps, to the most intriguing question of all, at least for readers of this magazine: Was the water hole shooting incident, as many maintain, the reason why John Henry Holliday was forced to leave his family for Texas and other parts west? It isn’t likely that any amount of historical investigation will ever confirm that one way or the other. It seems strange, though, that at a time when violence against blacks in the post Civil War South was rampant, that authorities—any authorities—would have prosecuted Holliday for a shooting in which the only witnesses who could have offered damaging testimony were a handful of black youths. The local lawyer who couldn’t have successfully defended Holliday in a case like that would have been lucky to find himself a job as an assistant clerk. Even if the threat of prosecution was real, Doc’s relocation to Texas wouldn’t have done him any good if he was on the run from federal authorities, as Texas was also occupied by federal troops. (Holliday certainly made no attempt to hide his identity in Texas and even got his name in a couple of newspapers for minor scrapes.) But federal authorities didn’t seem to know who he was, not until they read reports of his much publicized jail time in Colorado in 1882 after the vendetta ride with Wyatt. County criminal records of the period may be lost, but if Doc was wanted by federal authorities, surely some records attesting to that would’ve survived. At any rate, none has been discovered.

The Doc Holliday water hole shooting incident is and will likely always remain a mystery. Probably there was some sort of shooting, but one that was blown out of proportion either by Doc, Bat Masterson or perhaps even Alfred Henry Lewis, who had no qualms in his most famous Wolfville novel, The Sunset Trail (published in 1905), in inserting himself in Doc’s psyche.

“I mixed up in everything that came along,” Lewis’ fictional Doc says to the fictional Bat in The Sunset Trail. “It was the only way I could forget myself.” Nearly 120 years after his death, we’re still enthralled with Doc Holliday’s mix-ups.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Lowndes County Museum in Valdosta, Georgia –

– True West Archives –

– Sullivan photo: Courtesy Timothy Sullivan; Holliday photo: Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –