I take a deep breath and stare at the glacier-capped Wind River Mountains. My quarter horse Hank has probably seen this view a hundred times, but he stands quietly while I take it all in. I’m riding out amongst the low sagebrush and honey colored grass at the T Cross Ranch, and I’m feeling at peace with the world.

I take a deep breath and stare at the glacier-capped Wind River Mountains. My quarter horse Hank has probably seen this view a hundred times, but he stands quietly while I take it all in. I’m riding out amongst the low sagebrush and honey colored grass at the T Cross Ranch, and I’m feeling at peace with the world.

During the winter of 1889-90, outlaw Butch Cassidy, under the name George, hid out near the Wind River Mountains in Dubois, Wyoming, where he was quite friendly with his ranching neighbors.

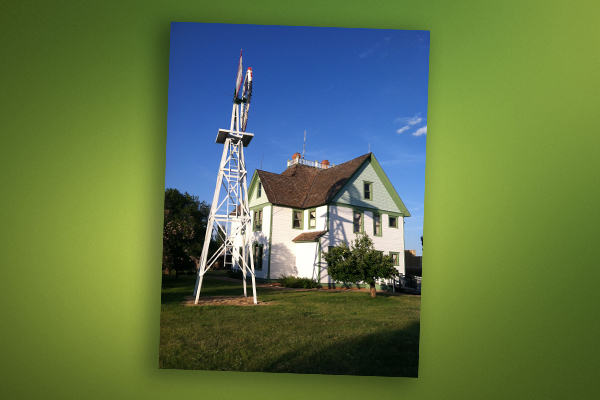

He knew John and his wife Margaret Simpson, who operated the local post office. Their cabins were the foundation for the first dude ranch in Fremont County, when the CM Ranch began operation in 1920. You can still ride your horse on over to the ranch at the mouth of Jakey’s Fork Canyon.

Cassidy also worked on Eugene Amoretti’s EA Ranch. It is likely Cassidy first met another ranch employee, Al Hainer, at this ranch. He and Hainer eventually teamed up to steal horses, for which they both paid the price when they were sent to jail in Rawlins in 1894. The working cattle EA Ranch still lodges guests in cabins set along Horse Creek.

Obviously Cassidy didn’t know Henry Seipt, a Spanish-American war veteran who bought a ranch he called the Hermitage in 1918, eventually operating it as a dude ranch. The ranch was first formed in 1862, though, so the outlaw may have known its original owner. The Hermitage is today’s 160-acre T Cross, named after the brand of Bob and Helen Cox, who purchased the ranch in 1929. Ken Neal, a retiree who turned the day-to-day ranch work over to his kids, owns it now.

“People who come to dude ranches have a curiosity about what was,” says Neal, whose memory of ranch life stretches back to when he was four years old. “Fortunately, we still have some area left that shows what it was like.”

When I enter my cabin at T Cross, I’m struck by the effect of the natural light and cool mountain air that drifts in through the open window. The owners of the T Cross use original material to replace and repair broken structures like the wooden latch on the door in my cabin. This kind of attention to detail demands a lot more work. The extra care allows T Cross to retain much of the character it has possessed since the late 1800s. I fully appreciate this work when I lie down to sleep in a bedroom that has remained virtually unchanged for 100 years. The feel of the wood bed frame and the subtle aroma of pine lull me to sleep.

“I find that people come and all of a sudden, after three days, they relax and they start to enjoy life, because they can’t get a lot of outside information,” Neal says. “It’s not available, and they quit looking for it. It’s a wonderful thing.”

In true T Cross style, I see many of the guests embracing an off-line lifestyle, doing absolutely nothing save rocking in a chair on the porch and staring at the horses in the pasture. I decide to postpone idle bliss for a few more hours and ride out into the unknown.

I always feel like a modern-day explorer when I’m investigating a new area on horseback. The rest of the world fades from my mind when I realize that an ant colony is the closest I will come to civilization for hours at a time. Maybe this is how the Shoshone Indians and Lewis and Clark felt when they rode the lands around T Cross in an infant America.

Many of our nation’s ranches are shrinking, remodeling or flat-out selling. Many of these ranches, where generations of families rode in the footsteps of homesteaders and Western legends, are fighting extinction by broadening their appeal with modern amenities like luxury spas. Inviting as these spas may be, the few ranches where Western life is faithfully maintained are precious. At the spa-free T Cross Ranch, riding and fly-fishing are my main activities. My attempt at fly-fishing is only moderately successful. I catch one small and shiny Cutthroat Trout. It’s “catch and release,” so I let my fish swim another day.

As my horse Hank takes a break, I drive to Dubois on a long, unpaved road, paralleling a trapper route blazed by Kit Carson and Jim Bridger in the 1800s. The Dubois Museum shows a glimpse of life back thousands of years before the West was settled by whites. It exhibits stone tools and petroglyphs of long-gone inhabitants. When I return to the T Cross Ranch, I finally succumb to blissful idleness and watch the Wyoming sunset.

I find a certain freedom, especially in today’s networked world, to riding all day and disconnecting from everything. The EA, T Cross and CM Ranches help protect these vast and untamed lands, allowing us to quell our curiosity about the past while we get away from the unending demands of our modern lives.

Butch wrote about his peaceful stay in Dubois to his brother Dan, telling him he was “raising horses, which I think suits this country just fine.”

I couldn’t agree more.