By 1887, Doc Holliday was in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, taking in the healing waters, trying to nurse his lungs that had been ravaged by tuberculosis.

By 1887, Doc Holliday was in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, taking in the healing waters, trying to nurse his lungs that had been ravaged by tuberculosis.

But the sulfur from those waters might have done him in. Bedridden by the fall of that year, Doc died in the Glenwood Springs Hotel on November 8 at the age of 36, by some accounts, prematurely gray and rail-thin.

Enter one William Forsyth McIlwraith. Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1867, he moved to the U.S. in 1887. On his way to Oregon, he went through Colorado, and it’s just possible that he ran into a dying Doc Holliday.

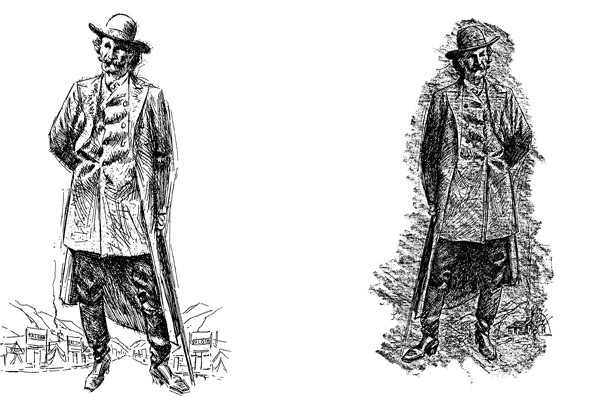

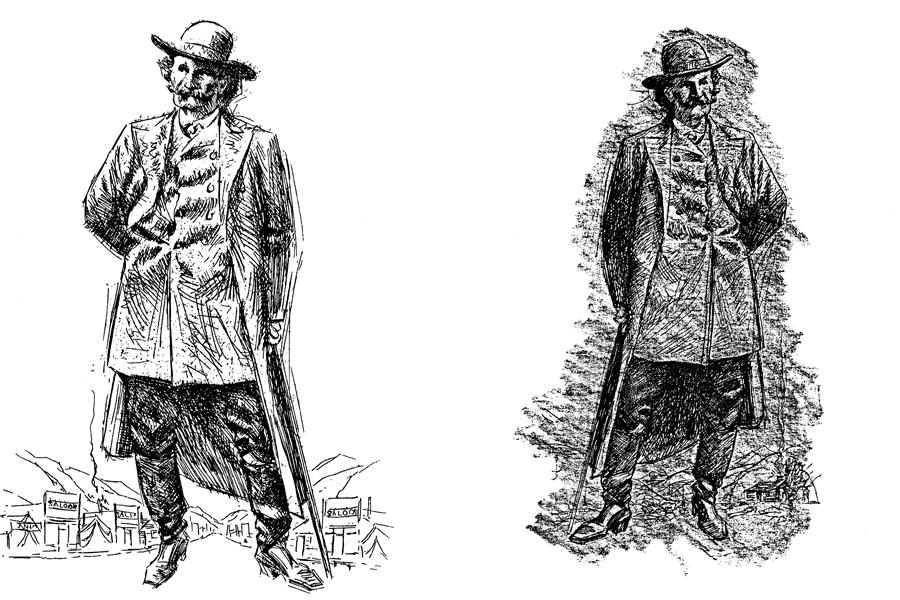

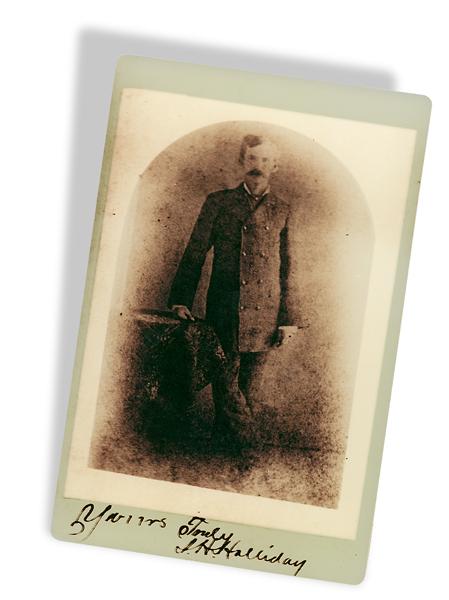

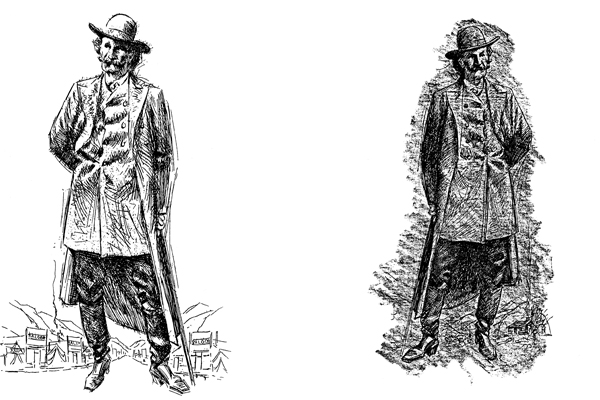

These etchings—which are probably in print for the first time—were found by Mark Dworkin of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in Yale University’s Stenzel Collection of Western Art at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Even though he wasn’t known to create portraits from life, the etchings are definitely McIlwraith’s work. They depict a handsome, stylish, thin man with an aquiline nose—a description that certainly fits Holliday. One etching shows cabins at the man’s feet; the other uses a mountain mining town as a backdrop (maybe Glenwood Springs?). Someone mislabeled this last etching as depicting Wild Bill Hickok. In both portraits, the character wears a diamond stickpin and double-breasted jacket—the same items worn by Holliday in a photo taken in Prescott, Arizona, in 1879.

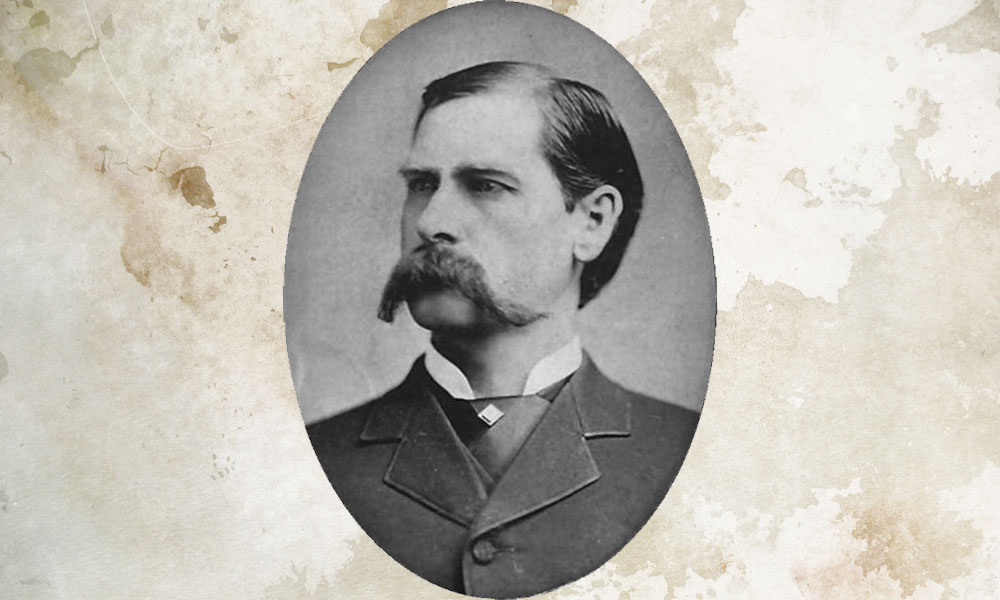

Gary Roberts, the author of Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend, thinks these etchings could definitely be of a dying Doc. No, there’s no definite proof. But if they are of the legendary gunfighter, the works may capture a melancholy late-period Holliday not seen in known pictures of him. At the very least, a case may be made that the etchings hold the key to understanding how Doc Holliday looked, dressed and perhaps felt in his final year—at least, in the eyes of one artist. He is a tall, slender, tired old man, slightly mismatched in attire, posing for a snapshot. His seasoned face sags like a worn tapestry. This can’t be the countenance of the dashing lawman who chased men across the West, or the Don Juan who wooed women in saloons from Peoria, Illinois, to San Diego, California. Yet this photograph may depict Wyatt Earp at 78 years old, in Los Angeles, two years before his death in 1929.

At the time, the old man was being deposed in a case involving the estate of legendary mining camp actress Lotta Crabtree. She’d been dead for three years, and she’d never had children. But a woman claiming to be the illegitimate daughter of Lotta’s brother Jack demanded her share of the Crabtree inheritance. The estate included millions of dollars—most of it left to charity. Earp had known all the principals, so he was asked to give testimony. Pamela J. Potter of Mountain Center, California, found a photo (shown at far left) and his deposition in the case files at the Harvard Law School Library.

The shot is labeled “Wyatt Earp,” but it does not note the date, time, place or name of the photographer. Maybe someone working on the case took the picture, or maybe Wyatt gave it to someone involved in the suit. In any case, it could well be one of the last photos taken of a Western legend.

First published last year in the Quarterly of the National Association for Outlaw & Lawman History, the photo has been relatively unknown for nearly 80 years. That’s not been the fate of the man in the picture—“long may his story be told,” indeed.

Photo Gallery

–Courtesy Mark Dworkin–

–Courtesy Craig Fouts –