At the edge of the Red Desert, But situated in a lush valley within view of a mountain range that retains snow on its peaks much of the year, Fort Bridger was strategically located on the route many emigrants and freighters used when traveling across the West.

At the edge of the Red Desert, But situated in a lush valley within view of a mountain range that retains snow on its peaks much of the year, Fort Bridger was strategically located on the route many emigrants and freighters used when traveling across the West.

The man for whom the fort is named, Jim Bridger, had the opportunity to select a location for a post at many beautiful areas of the West for he had traveled all across the region. Most particularly he roamed the Upper Green River Country of Wyoming, north into Jackson Hole, and west into Pierre’s Hole and the Bear River Valley of Idaho.

Bridger, born in Virginia and a migrant with his family across the Blue Ridge to Missouri when he was still a child, came of age in St. Louis. Just past age 18, Bridger answered the call of William H. Ashley in 1822 for 100 young men to ascend the Missouri and enter the fur trade.

Street smart with skills on the river and in a blacksmith shop, Bridger was illiterate. Nevertheless, he would develop his life skills and tramp the West, creating a map of it in his head that he would later share with many travelers—from emigrants to Mormons, and freighters to frontier troops.

Bridger, like the other men who worked for Ashley and Maj. Andrew Henry, spent time at Henry’s fort, located at the mouth of the Yellowstone River in present-day Montana. He’d already been involved in a battle with Arikara Indians, and then he abandoned Hugh Glass, leaving him for dead following a mauling by a grizzly bear. Working for Ashley and Henry gave Bridger an opportunity to learn the mountain trade so he could become a free trapper working for himself. Early on he trapped along the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, but before long, he had pushed into the high mountain valleys of Wyoming and Idaho.

To begin tracing his trail, we will start in Billings, Montana, along the Yellowstone River, traveling west along Interstate 90 to Three Forks, where the branches of the Missouri come together. Bridger traveled this region in his earliest days in the West; he would later forge a trail from the Oregon Trail (near Casper, Wyoming) to the goldfields of western Montana, near Alder Gulch—the site of present-day Virginia City.

Bozeman Pass to Jackson’s Hole

Our route is through Livingston, Montana, over Bozeman Pass to the town named for John Bozeman, whose own trail to Virginia City was more heavily used than the Bridger Trail. From Three Forks, we turn west and south on U.S. 287 to Virginia City and nearby Bannack, the earliest capital of Montana Territory and now a state historic site.

Next we travel east and south on U.S. 287 and U.S. 20 into Island Park and Teton Basin at Driggs, Idaho, a location known as Pierre’s Hole during Bridger’s day. It is also the site of an 1832 battle between the trappers and Blackfeet Indians. Bridger defended himself, along with Tom Fitzpatrick, who was instrumental in organizing the mountain contingent into a defensive troop.

From this area of northeastern Idaho, head with me southeast on Idaho Highway 33 and Wyoming Highway 22, crossing Teton Pass and dropping into Jackson’s Hole, named for David Jackson, one of the men with whom Bridger partnered in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. If you have a vehicle with decent clearance (my Subaru Outback made it with some careful driving), take the less traveled road into Jackson Hole by following the Grassy Lake Road from Driggs, Idaho, east at the southern boundary of Yellowstone National Park to Flagg Ranch, just south of the park entrance. Flagg is a good place for a meal, for a refill on fuel or to stay the night. Then travel south and west through Grand Teton National Park and across Jackson’s Hole into the town of Jackson.

I recommend taking time to hike or ride horseback through the park (numerous outfitters in the area can provide you with guide services). Be sure to stop at the recently opened Craig Thomas Visitor’s Center in Moose, eat a delicious dinner at Dornan’s near Moose and cap the night with a drink at the Cowboy Bar or the Silver Dollar Saloon in the Wort Hotel in Jackson. For few frills and a good bargain lodging choice, stay at Cowboy Village. If price is no object, choose the Wort.

Meet Me On the Upper Green

After feasting on a big breakfast of sourdough flapjacks at Jedediah’s House of Sourdough, travel south on U.S. Highway 189/191 through Hoback Canyon and into the upper Green River Valley. Of all the time Bridger spent in the West—and all the places he explored—almost certainly he devoted a large portion of it to the Upper Green. He trapped here and attended the six rendezvous held in the area. He even met Brigham Young and the Mormons as they traveled toward the Great Salt Lake Valley in 1847 (the meeting took place near the Little Sandy Crossing of the Oregon Trail east of Farson, Wyoming).

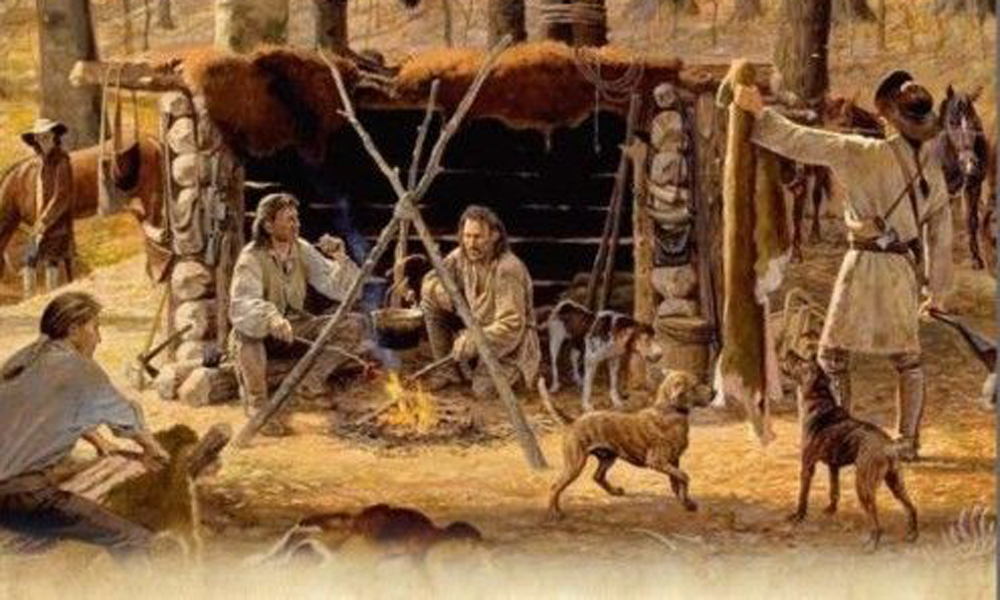

A stop in Pinedale at the Museum of the Mountain Man is required on a journey following Jim Bridger across the West, for the museum celebrates the era of the mountain man, and it has on display a gun once used by Bridger.

From Pinedale continue south on U.S. 191 to Farson, and take Highway 28 west linking into U.S. 189. Take a short detour to the north, toward Big Piney. At Names Hill, you can view a rock inscription “Jim Bridger, 1844.” Almost certainly Bridger was in this area, though since he was illiterate, it is doubtful that he actually carved his name here.

Remain on U.S. 189 but turn southwest to Kemmerer and take U.S. 30 west to Montpelier, Idaho. This was a route for Oregon- and California-bound travelers, but Bridger came this way to trap the cold streams flowing into the Bear River.

Then turn south once again, traveling along U.S. 89 through Logan, Utah, and then south on I-15 to the Salt Lake Valley. Bridger is one of the first non-native adventurers known to be in this area. The home base of the Mormon Church, which established itself in this part of the West in 1847, Salt Lake City hosted the Olympics in 2002 and is now reinventing its downtown, where a plethora of high-rise cranes are placing steel girders in anticipation of a new center that will include lodging, dining and shopping.

Bridger’s Favored Country

Traveling east on I-80 takes us back into Wyoming and Bridger’s favored country, a place still known as Bridger Valley. Old Gabe first saw the Blacks Fork of the Green River during the first mountain man rendezvous in 1825. In 1842, with his partner Louis Vasquez, he opened a trading post on Blacks Fork that he knew would be “in the path of the emigrants.” Fort Bridger soon became one of only a few trade sites along the route to Oregon. It was 500 miles west of Fort Laramie; more than 200 miles from Fort Hall, Idaho. Bridger owned and operated the post for 10 years. In 1852, it was under control of the Mormons. They always said they purchased the fort from Bridger; he always said they stole it.

The mountain man-era trading post gave way to the military, which kept it in service until 1890. Today it is a Wyoming State Park with restored buildings from the military era and a recreation of Bridger’s post, complete with a trader on site during the summer. Out front you are welcomed by a heroic-sized statue of Jim Bridger.

Bridger guided wagons, gave advice to travelers (as he did to Brigham Young and the vanguard of the Mormon Trail in 1847) and scouted for military expeditions on his trail. Continue east on I-80 to Rawlins. South of the city, you will find remnants of the Overland and Cherokee Trails, traversing a pass named for Bridger.

From Rawlins circle to the northeast on U.S. 287 and Highway 220 to Casper, where you can visit the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center and Fort Caspar. Complete the circle and head west along U.S. 20. Turn north to cross into the Big Horn Basin passing through today’s Worland, traversing the badlands and exiting at the small town of Frannie to eventually merge with Bozeman’s route.

Thanks to this trail Jim Bridger blazed, prospectors in the 1860s had a safe and fast route to the goldfields at Alder Gulch.