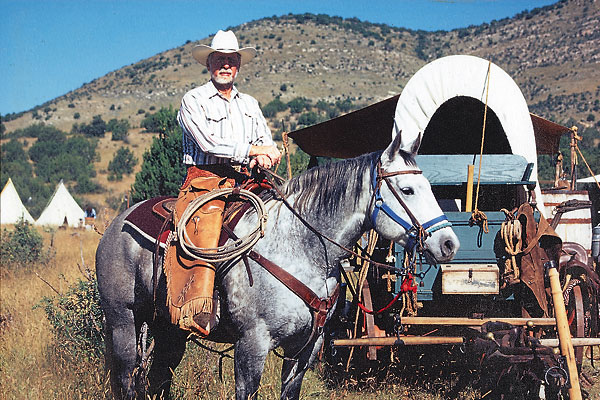

Today, Sid Goodloe has a lush vista from his two-story ranch house.

He can see for miles, looking at low hills and pine trees and thick grassland (to say nothing of the 10,000-foot mountains in the background), but that’s sure not what greeted him when he found this hunk of New Mexico in 1956.

“The land was so abused; it was cheap, and I didn’t have any money,” he remembers. Like so many before him, he’d “gone West” seeking a place to establish the ranch he knew he wanted since he was a kid. He found 3,500 acres some 20 miles northwest of Capitan. An older, richer man would have looked at the “mess” this land had become and given it a pass.

But Goodloe was young and strong, with the spunk to take on land that had been overused since the Civil War. Not only had it been overgrazed with sheep and cattle, but the Forest Service had habitually put out the fires that normally cleanse grassland of trees, so the property was overpopulated with piñon, juniper and ponderosa. “The first thing I did was start clearing the land—it’s been 50 years, and I’m not done yet,” he says.

If Goodloe had been the same kind of rancher that this land had seen in the past, it wouldn’t be the heavenly place that he so loves today.

“We don’t graze in the uncontrolled way that caused the abuse,” he says. “That’s called continuous grazing. We do rotational grazing; we mimic the buffalo. It’s that simple.”

To a common-sense guy like Goodloe, it’s simple, but his approach—call it a model of “sustainable ranching”—is considered controversial in some circles. Ranchers, by their very natures, are independent, so change doesn’t come easy. Goodloe isn’t bothered by this, because he’s seen his approach works.

About those buffalo: “They’d come in and intensely graze, leave behind dung and urine, stir up the soil with their hooves and then move on,” Goodloe explains. All that re-fed the soil, giving it the nutrients to grow a new crop. That simple model is how he grazes his 100 Angus mother cows, giving a pasture time to recover as the herd rotates from place to place. Farmers also do this, he notes, when they rotate their crops so the natural nutrients will be replenished, like planting corn one year and alfalfa the next to get nitrogen back in the soil.

He doesn’t think anyone moved to the West and tried to ruin the land; they just didn’t know any better. “They thought they’d found paradise, and they didn’t realize the profound droughts we have are a part of life,” he says. “First sheep abused the land and then cattle; it was the height of human naivete.”

When he started his approach of sustainable ranching, he found acceptance was hindered by a “wall” that had built up between ranchers and environmentalists. “The environmental community has caused a lot of problems, trying to tell people who have ranched for generations how to run their ranches,” he says. ‘This is a hard place to make a living, and it takes stubborn, self-reliant people to make it. So you can’t come in just out of college and tell someone how to do it.”

Goodloe is trying to tear down the wall. He’s on the board of directors of the Quivira Coalition, a 10-year-old effort to get both sides to talk to one another.

At the same time, people come from New Mexico and Texas and other parts of the West to see what his approach means. His ranch is a model that many would like to copy. “We have lots of tours and workshops to learn about environ-mentally sensitive ranching,” he says.

To make sure his children and grandchildren have the opportunity to be New Mexico ranchers, Goodloe has put his land in a conservation easement that extinguishes his development rights so it will forever remain ranchland. He hopes that experience will give his kin the “work ethic, dependability and innovation skills that will make them the future leaders of our country.” He’s on his way with a daughter and two granddaughters who live on the ranch. “They’re my cowboys,” he says. “I have an all-girl cattle crew.”

At the end of the day, the land was very good to Sid Goodloe, just as he was very good to the land. He’s a man who has saved 3,500 acres of the Old West and pointed the way to save much more.