A broken wagon spoke deserves all the credit.

A broken wagon spoke deserves all the credit.

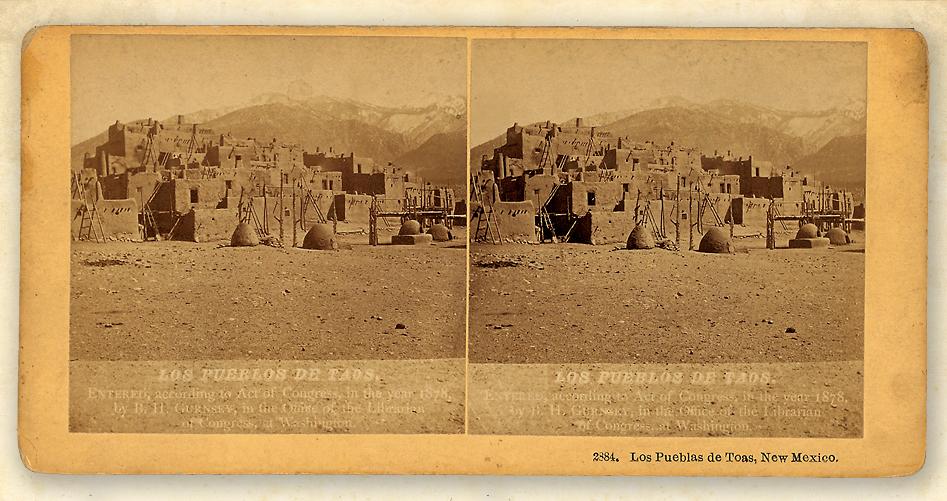

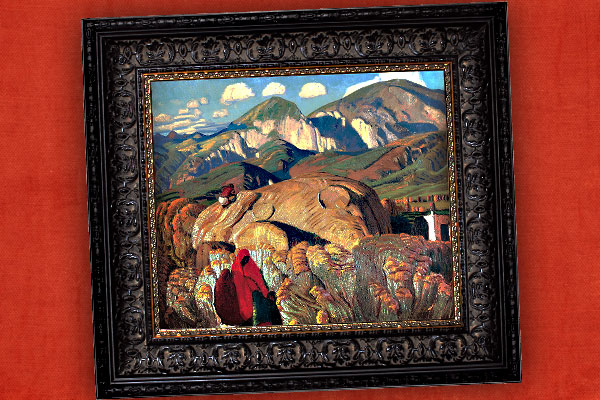

Think about it. Needing to repair their wagon, Eastern artists Bert Geer Phillips and Ernest Leonard Blumenschein stopped at a sleepy little village in 1898, and Taos, New Mexico, has not been the same since.

Phillips and Blumenschein wound up canceling the rest of their New Mexico tour to paint in and around Taos. Phillips stayed, while Blumenschein visited over the years, sharing the news about the place with his artist friends; he didn’t move there permanently until 1919, when he finally convinced his wife. Four years earlier, the two artists helped form the Taos Society of Artists, and by 1916, 100 painters were living in or regularly visiting Taos.

Artists soon began discovering Santa Fe, roughly 70 miles south. John Sloan, who had exhibited his work in New York at the Armory Show of 1913, began spending his summers in Santa Fe around 1918 and his winters in New York. Randall Davey, who also had artworks exhibited at the Armory, made his home higher up Santa Fe’s Canyon Road. His family donated his house to the Audubon Society; today, the Randall Davey Audubon Center & Sanctuary attracts bird watchers, artists and nature lovers.

By the 1920s, Los Cinco Pintores (“five painters,” or, as locals called them, “five nuts in the adobe huts”)—Jozef Bakos, Fremont Ellis, Walter Mruk, Willard Nash and Will Shuster—brought national attention to Santa Fe’s art colony.

Names have changed and numbers have grown, but Taos (with 1,000-plus artists and more than 80 galleries) and Santa Fe (where just about everyone is an artist, and where you’ll find some 200 galleries) remain art meccas.

“I’d heard artists came here for the light,” says Thom Ross, artist and owner of Santa Fe’s Due West Gallery. “Not me. I don’t try to mimic natural light. But there’s no question the atmospheric beauty of this place is beyond belief. I come here because of the myth, the Conquistadors, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, the Anasazi. Man, to be in the fifth-largest state and there’s no one here. I love that!”

New Mexico houses a population of just more than two million, and it certainly attracts tourists, especially art lovers. In Santa Fe and Taos, you can soak up a lot of great art, sights and history.

In the City Different

In Santa Fe, you should begin your trip at the New Mexico Museum of Art, where “It’s About Time: 14,000 Years of Art in New Mexico,” which closes January 5, details Southwestern art from pre-contact Clovis culture to New Mexico’s centennial celebration of statehood.

Across the street, Indian artists daily display and sell their works underneath the portal of the Palace of the Governors, built in 1610, and the New Mexico History Museum offers exhibits on the state’s history. From there, you will want to check out the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, which showcases one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. The museum houses more than 3,000 of O’Keeffe’s works, from 1901 to 1984, when she retired two years before her death.

“I simply paint what I see,” O’Keeffe said, and she saw a lot of New Mexico, where she began spending time from 1929 through the 1940s. She moved to Abiquiú, between Española and Chama, full time in 1949.

Then, of course, you will want to visit Santa Fe’s art galleries. Ross isn’t alone at Due West. You also can find: Adobe, Altermann, Barbara Meikle, Joe Wade, Legends Santa Fe, Manitou, Medicine Man, Nedra Matteucci and Zaplin-Lampert. The third-largest art market (behind New York and Los Angeles), Santa Fe is thankfully not full of art snobs who look down upon Western art.

Although the quality of the art does matter here. As Ross says, “I don’t want to see a scribbler who’s just copying a cowboy wearing a rain slicker.”

Western art is clearly on the rise in this town. “There is definitely room to make a new look in the Western drama,” says Bill Schenck, whose works hang at Manitou Galleries. “There’s tons of room. You can take it in God knows how many different directions. You can explore and come up with a new look.”

Rolling on the River

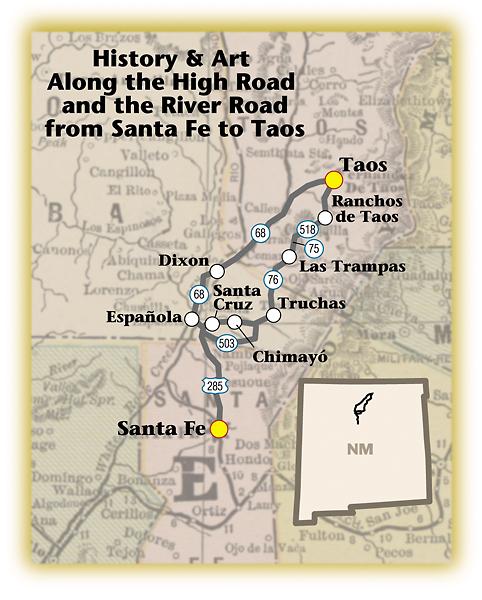

When it’s time to head north to Taos, you have a choice between the River Road (or the Low Road) or the High Road. I’ll take the River Road up, and the High Road down.

For the River Road, travel U.S. 285 north to Española, where the Bond House, built between 1887 and 1911 by a railroad pioneer, is now a museum detailing the region’s history. Then follow state highway 68 along the Rio Grande. Don’t drive fast. Enjoy the scenery. Whatever you do, don’t miss Dixon.

Located along the Embudo River, a tributary of the Rio Grande, Dixon was settled by Indians from Picuris Pueblo and then Spanish colonists in the early 1700s. For art lovers, the annual Dixon Studio Tour (November 2-3) features roughly 40 artists creating paintings, sculptures, jewelry, ceramics, photography and weaving. If you agree making wine is an art, Dixon is home to two New Mexico favorites you will want to try, Vivác and the always tasty and friendly La Chiripada.(Just don’t sample too much before you continue driving north.)

Swing into Ranchos de Taos, on the outskirts of Taos. The San Francisco de Asis Mission Church, built between 1772 and 1816, remains one of the most popular churches for artists. O’Keeffe painted it. Ansel Adams and Paul Strand photographed it.

Taking in Taos

Drive slowly into Taos. You will have to, as traffic is always slow in Taos.

“I had no idea the place was so beautiful,” Indian artist R.C. Gorman told me shortly before his death in 2005. “I just came to check the galleries out.”

Gorman’s legacy remains at his Navajo Gallery. Parsons Gallery of the West showcases historic and contemporary art. Tony Whitecrow has been making deerskin art and Western collectibles since settling in Taos 28 years ago. “This is an enchanting place,” Whitecrow says.

Taos brought out the art in Max Evans, before he put away paintbrushes to paint scenes with words in novels such as The Hi Lo Country and The Rounders. It even brought out art in author D.H. Lawrence.

The Hotel La Fonda de Taos is home to Lawrence’s “Forbidden Art.” This series of nine oil paintings was deemed obscene in 1929 and banned in London. By today’s standards, the artworks are tame, and, well, history records Lawrence as a better novelist than painter.

You can find a different kind of art, Western kitsch, at Horsefeathers. Lindsey Enderby ran it for 24 years before selling the store in June.

Yet true lovers of art and history should check out two magnificent museums in Taos. The first, the Harwood Museum of Art, founded in 1923, showcases historical works from its permanent collection plus changing exhibitions of contemporary art created primarily by New Mexico artists.

My favorite is the Millicent Rogers Museum. A New York society heiress weakened by her childhood bout with rheumatic fever, Rogers arrived in Taos in 1947 and collected Indian art until her death in 1953. The museum includes her collection plus regional art and artifacts.

Ride the High Country

When you are finished exploring Taos, drive back to Santa Fe. But this time, take the High Road.

This winding, 56-mile byway starts at N.M. 518 at Ranchos de Taos and then takes you along state roads 75, 76, 98 and 503. Yes, it’s easy to get lost. I did.

The San José de Gracia Church, completed in 1776, in Las Trampas might be as popular with photographers and tourists as the church at Ranchos de Taos. Truchas, established by a 1754 land grant to slow down Comanche and Apache raiders, served as the set for the 1988 film version of The Milagro Beanfield War, based on the novel by John Nichols.

Chimayó is home to one of the state’s most famous churches, Santuario de Chimayó, built between 1810 and 1816. After WWII, Bataan Death March survivors started walking to the church to thank Santo Niño de Atocha for their deliverance. Many believe the dirt at the church has healing powers. Every year, some 300,000 visitors come to the church, including roughly 30,000 who make a pilgrimage during Holy Week before Easter.

Chimayó is also home for its famous red chile powder, but for art lovers, Chimayó is all about weaving. A century ago, weavers helped create a distinct style of energetic colors and unique designs. Gabriel Ortega settled in the area in the 1700s and began weaving. Eight generations later, Ortega’s Weaving Shop continues that tradition in a building that the family built in 1948. Today, about 20 weavers create wool rugs, blankets, coats, vests, coasters, place mats, pillows and purses.

“We’ve been here a long time,” Robert Ortega says, “and we’re not planning on going anywhere.”

Before the High Road ends in Española, slow down as you’re driving through Santa Cruz. Theresa Montoya’s art gallery carries some 200 retablos. These paintings of saints on wooden panels can be found in just about any gallery or tourist trap in northern New Mexico, but Montoya’s aren’t always so traditional.

A diehard fan of the Beatles, Theresa’s husband, Richard, began turning the Fab Four into the Holy Four. “They tell me I’m stuck in the ’60s,” Richard says, “but I say, ‘What a fabulous place to be.’”

Although Richard has been sidelined after a heart attack, Theresa and her son, Rick, continue his style.

They do so because Santa Fe and Taos and every spot along the River Road and the High Road aren’t just art colonies, they are spiritual places, no matter your faith.

“It’s faith that drives people here,” Theresa says.

Faith, and art and history.

As much as Johnny D. Boggs loves Max Evans and Tony Hillerman, his favorite New Mexico novel is Red Sky at Morning by Richard Bradford.

Photo Gallery

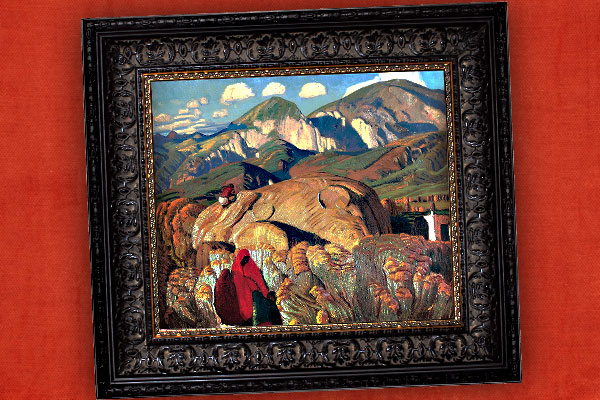

– Courtesy E.L. Blumenschein Home and Museum –

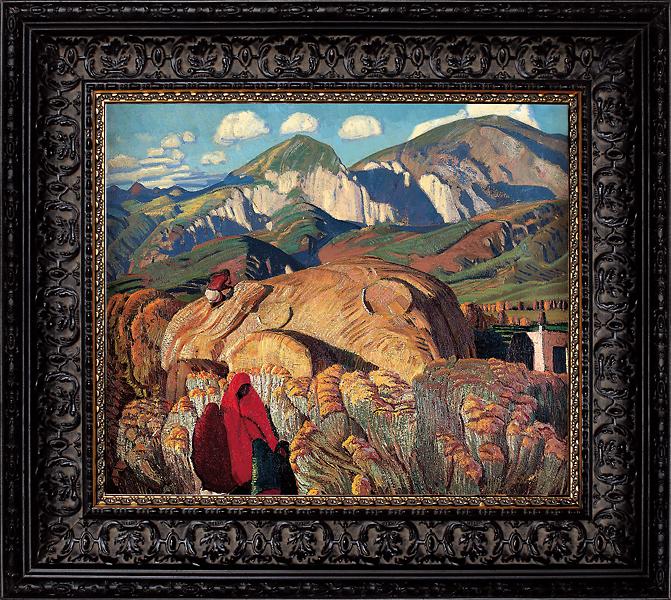

– Courtesy Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma, Norman; Given in memory of Roxanne P. Thams by William H. Thams, 2003 –

– True West Archives –

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –