Custer stories never seem to die out.

Custer stories never seem to die out.

But even if Custer had never been a part of this story, it would be a good one, involving among other things a record-making trip by a river steamer down 700 miles of mostly uncharted Western waters, the longest telegram ever sent, a denial by the U.S. Army that Custer had been defeated by the Sioux and one of the greatest newspaper scoops in journalistic history.

It began with a notebook, written by Mark Kellogg, a reporter from the Bismarck Tribune who had accom-panied Custer and the Seventh Cavalry into the Montana country. After the June 25, 1876, battle, his notebook was found by his body and given to Capt. Grant Marsh of the river steamer Far West to be returned at some point to the Tribune’s editor, Clement A. Lounsberry.

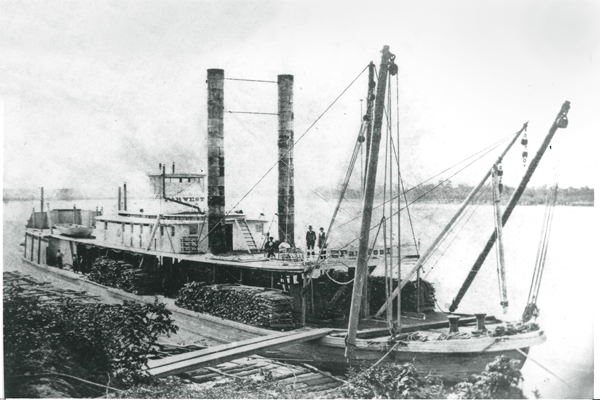

In the previous weeks, the Far West had been carrying supplies for the U.S. Army forces in the West and was making a tortuous trip up the Missouri, Yellowstone, Bighorn and Little Bighorn Rivers. By the time it reached the Little Bighorn, the Battle of the Little Bighorn was over. Almost immediately, Marsh was ordered to turn the steamer around and head back to Bismarck in Dakota Territory as fast as he could. It was imperative to get the Army’s report of the battle to Gen. Philip Sheridan in Chicago. The nearest telegraph line to the East was at Bismarck—700 miles away. No river boat had ever before made that trip, but with a mournful toot of its steam whistle, its boilers filled to capacity and with black cloth draping its smoke stack, the Far West started off, racing down the rivers, stopping only to yell out the news and to take on more firewood. In 54 hours, the steamer reached its dock at Bismarck, a record that in all the years that followed was never equaled.

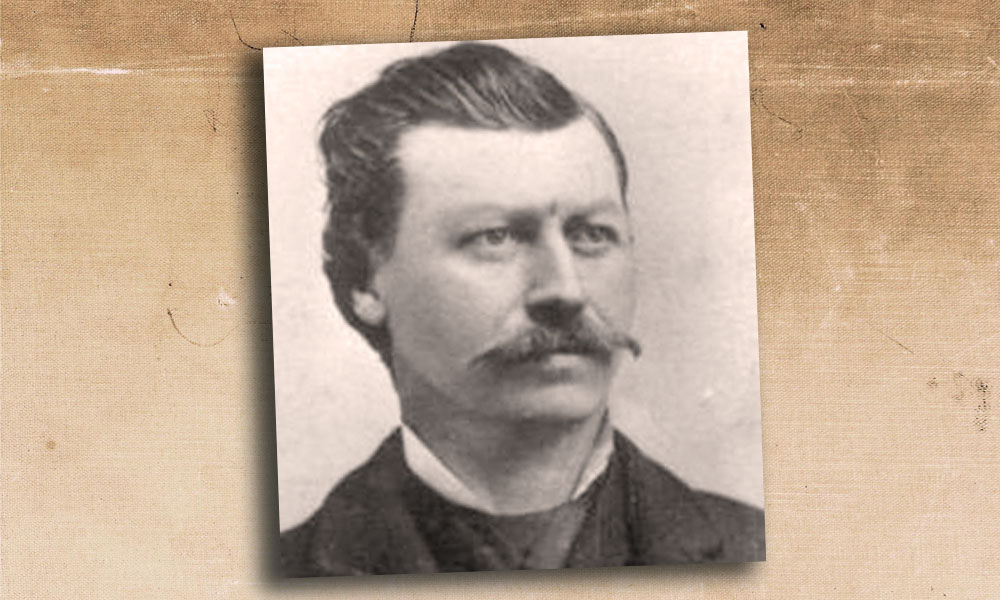

While Army personnel rushed over to the telegraph office to send the official report to Chicago, Marsh sought out Lounsberry and handed him Kellogg’s notebook. Lounsberry could hardly believe what he held in his hands. A stringer for The New York Herald as well as the editor of The Bismarck Tribune, he jumped into action, running over to the telegraph office where the sole telegrapher in town, J.D. Carnahan, had just finished transmitting the Army’s report. Lounsberry told Carnahan, “Don’t give up the line to anyone. The Herald will pay all charges,” and he began dictating some of the notes from Mark Kellogg’s notebook. On and on he dictated while Carnahan’s telegraph key clicked and clicked. The events leading up to the battle, the complete casualty list he got from the Army, interviews with Grant Marsh and the expedition’s chief surgeon who had returned to Bismarck on the Far West, stories from the Far West’s crew—on and on he kept that line, and when he needed to go outside to get more stories, he shoved over to Carnahan a Bible sitting on a shelf, saying “If I’m not here to dictate, put in some of the lines from this to keep the line.” For an incredible 22 hours, Lounsberry dictated one newspaper feature after another—an estimated 15,000 words of text in what was said to have been the longest telegram ever sent.

Meanwhile in the New York office of the Herald in Park Row, the presses were stopped the minute Lounsberry’s copy started coming in, and the front page was redone to make room for the Custer story. When the morning edition hit the streets on July 5, 1876, New Yorkers had trouble believing the news.

General Custer Killed…The Entire Detachment Under His Command Slaughtered….Narrow Escape of Reno’s Command.

The other New York papers were caught flatfooted, and some challenged the Herald’s account. One pointed out that the Herald was not adverse to fabricating stories. Several years before, it had published an article stating that all the animals from New York’s Central Park Zoo had escaped. It wasn’t until one reached the end of the article that a disclaimer noted the entire story was fiction.

Back in Chicago, the Army’s official report of the Custer massacre lay on the desk of Gen. Sheridan, but he was not there. He was in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as an honored guest at the celebration of the nation’s 100th birthday. As he was being escorted around the grounds, a local reporter rushed up and handed him a copy of that morning’s Herald that had come from New York by train. Sheridan glowered and denied the story. “This can’t be true! If I don’t know about it, how could the Herald possibly know?” Several hours later, after he had returned to his hotel room, Sheridan received a copy of the official Army report, which had been found on his desk and re-transmitted to him.

For four more days, the Herald ran Custer stories until finally there was no more text left from Lounsberry’s telegram. The newspaper had scored one of the greatest scoops in journalistic history.