Throngs of people descended upon Jacksboro, Texas, on a hot summer day in 1871 to witness a murder trial. Murders were commonplace in reconstruction Texas, but this would be no ordinary event. Cause No. 224 (actually two trials held July 5-6) would be the trial of the century.

Throngs of people descended upon Jacksboro, Texas, on a hot summer day in 1871 to witness a murder trial. Murders were commonplace in reconstruction Texas, but this would be no ordinary event. Cause No. 224 (actually two trials held July 5-6) would be the trial of the century.

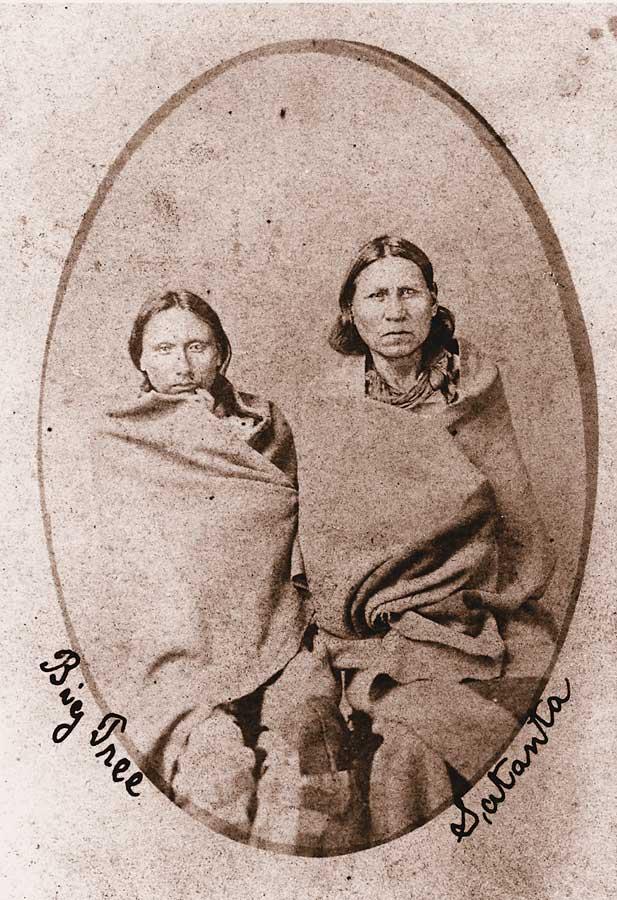

Facing the gallows were Kiowas Satanta and Big Tree, the first Indians to be tried under white civilian law. Of course, there was no way two Kiowas could receive a fair trial in Indian-ravaged Northwest Texas. On the other hand, it was equally obvious that Satanta and Big Tree were guilty.

Satanta was in his early to mid-50s and Big Tree was about 19 or 20 when they joined prophet and medicine man Maman-ti, Satank and several other Indians as they left their reservation near Fort Sill, Indian Territory. On the Salt Creek Prairie between Belknap and Jacksboro, the warriors waited. Bowing to Maman-ti’s vision, the Indians let a military ambulance and mounted riders pass unharmed on May 17. The following afternoon, with a storm brewing, the raiders attacked a train of 10 wagons and 12 teamsters hauling corn. The men were employed by Capt. Henry Warren, who had a government contract delivering supplies to frontier forts.

For the Kiowas, the raid was a moderate success. They suffered a handful of casualties but made off with 41 mules, assorted plunder and six scalps (seven teamsters had been killed, but one was bald).

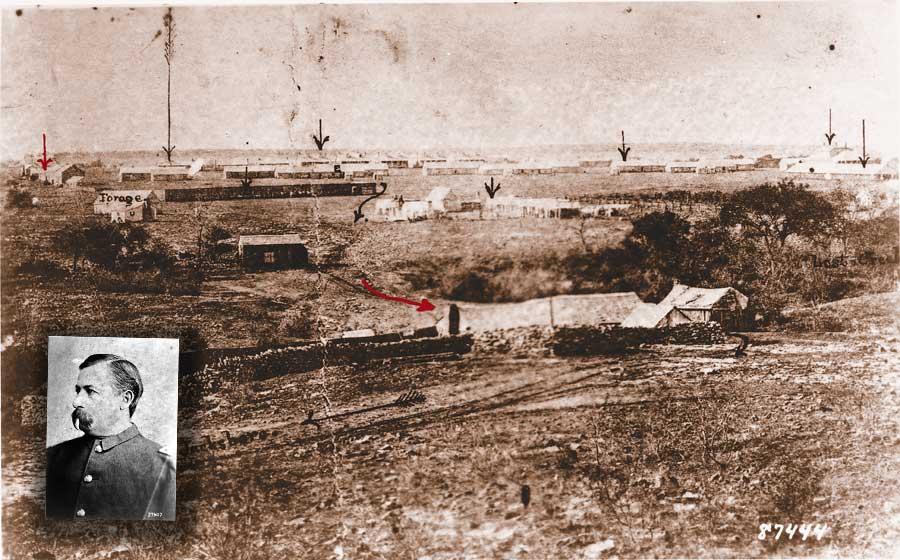

The ambulance Maman-ti let safely pass on May 17, however, had carried a distin-guished passenger: Gen. William T. Sherman, who was touring the Indian frontier and had been on his way to Fort Richardson at Jacksboro. Two teamsters—including wounded Thomas Brazeal—stumbled 20 miles through the rain to report the attack. When Sherman heard Brazeal’s story, he immediately ordered Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie of the Fourth Cavalry to pursue the attackers.

Sherman went on to Fort Sill, where with help from Lawrie Tatum, an Indian agent and conscience-troubled Quaker, and Col. Benjamin Grierson’s 10th Cavalry, Sherman arrested Satanta, Big Tree and Satank after Satanta admitted taking part in the raid. Maman-ti managed to escape Sherman’s net.

Both Sherman and Tatum believed punishing the Indians with the threat of hanging would decrease raids into Texas. “These three Indians should never go forth again,” Sherman wrote. “If the Indian Department objects to their being surrendered to a Texas jury, we had better try them by a Military Tribunal, for if from any reason in the world they go back to their tribes free, no life will be safe from Kansas to the Rio Grande.”

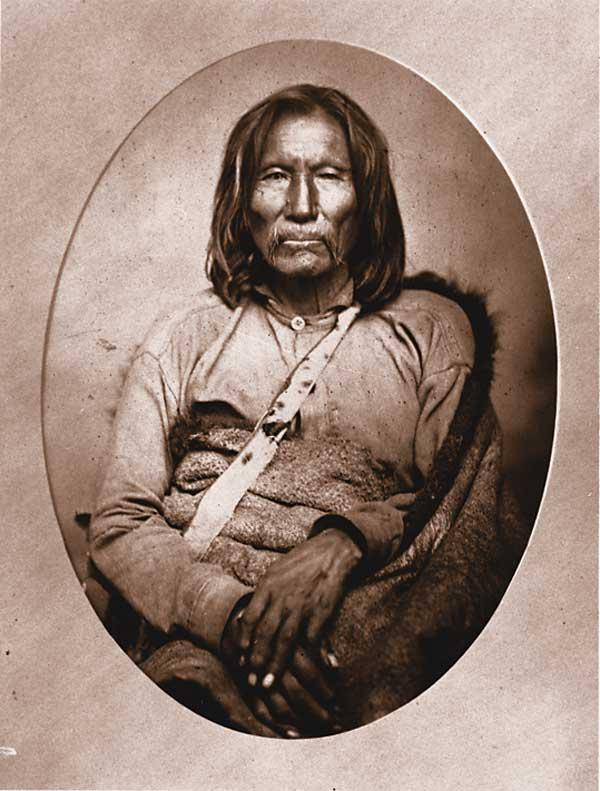

Mackenzie arrived on June 4 and departed with the three Kiowa prisoners four days later. In the lead wagon was the leader of the Koiet-senko warrior society—Satank, who was described by an Army and Navy Journal correspondent as “a hoary-headed old sinner sixty years of age or thereabout, grown gray in iniquity and deeds of blood.”

Covering himself with a blanket, Satank began singing his death song. Using a knife he had procured and his teeth, the warrior slipped free of his manacles. Less than a mile from the fort, he wounded a guard with the knife and grabbed a carbine before being shot to death, “preferring,” one newspaper said, “to die like a warrior than to enter the spirit-land by a dogs death at the end of a rope.”

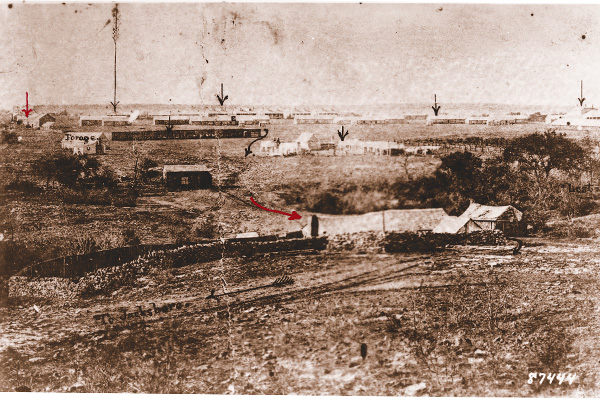

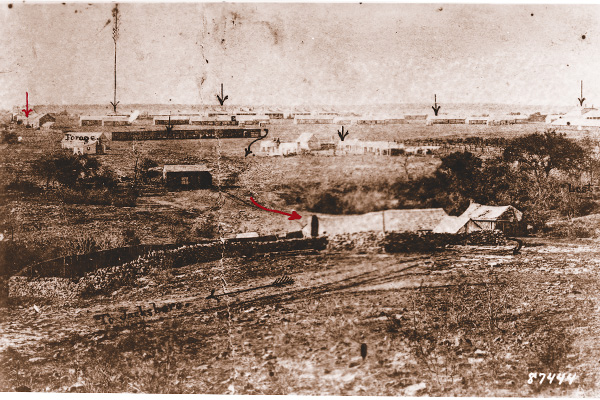

On June 15, Mackenzie’s cavalrymen and the two remaining prisoners arrived at Jacksboro to cheers from soldiers and civilians, and music from the regimental band. Satanta and Big Tree were confined at the fort.

Not everyone, however, seemed overjoyed at the prospects of such a monumental trial.

Eight lawyers—including Samuel W.T. Lanham and Thomas Ball—petitioned Judge Charles Soward of the 13th Judicial District, requesting court not be held at Jacksboro because of the Indian threat.

The petition was denied. Lanham served as prosecutor and Ball was one of the defense attorneys when the court met in the two-story courthouse July 1. On July 4, an indictment was handed down against Satanta and Big Tree for the murder of the seven teamsters. The trial began the following day.

School was dismissed, and people flocked to the courthouse’s top floor, where the case would be heard. Satanta and Big Tree arrived from Fort Richardson in a wagon, surrounded by soldiers to prevent anyone from shooting the prisoners. At 8:30 a.m., court was called into session.

The defense first entered a motion that the state had no right to try the Kiowas because the Indians were wards of the federal government. Soward rejected the argument, but granted the defense’s next motion to sever the trials. Big Tree would be tried first.

Ball opened the case with a plea for compassion. The Dallas Herald noted his “speeches were at some points most eloquent, and displayed not only a thorough knowledge of the Indian character,” but also proved Ball to be a great orator. In the stifling courtroom, he removed his coat as he described the wrongdoings done against Indians since the time of Spanish explorers. He finally asked the jury to let Satanta and Big Tree “fly away as free and unhampered” as an eagle. When this was translated for the Kiowas by Fort Sill interpreter Horace Jones, the Indians grunted and nodded.

Jones, Col. Mackenzie, teamster Brazeal, Sgt. Miles Varily and agency interpreter Mathew Leeper testified for the prosecution. Brazeal told the jury of the attack, Varily identified Kiowa arrows found at the site and Leeper—testifying on behalf of Indian agent Tatum—told how Satanta had boasted of leading the raid. Ball and Joseph A. Woolfolk asked few questions and called no witnesses for the defense. By early afternoon, it was time for closing arguments. If Ball had wowed spectators with his opening oratory, Prosecutor Lanham did the same in his closing.

“This is a novel and important trial, and has, perhaps, no precedent in the history of American criminal jurispru-dence,” he began. The understatement and politeness ended there.

Lanham noted the defendants’ “crude and barbarous appearance; the gravity of the charge; the number of the victims; the horrid brutality and inhuman butchery inflicted upon the bodies of the dead.” He called Satanta “the arch of fiend of treachery and blood . . . the inciter of his fellows to rapine and murder, ” while Big Tree was a “tiger-demon who has tasted blood and loves it as his food—who stops at no crime how black soever.”

It took the jury half an hour to come back with a guilty verdict. Court was adjourned. Satanta would get his day in court the following day.

Witnesses and testimony were predominantly the same. Yet, the testimony of Jones, reported the Dallas Herald, was “more conclusive and direct than that against Big Tree he having, before arrest, harangued his tribe and said: ‘Let no Chief claim the credit of killing those seven men in Texas, I am the Big Chief that did that killing.’”

This time, however, the defendant testified on his own behalf. Satanta, speaking in Comanche interpreted by Jones, pleaded:

“I have been abused by my tribe for being too friendly with the white man. I have always been an advocate of peace. I have always wished this to be made a country of white people. . . . This is the first time I have ever faced Texans. They know me not—neither do I know them. If you let me live, I feel my ability to control my people. If I die it will be like a match put to the prairie. No power can stop it.”

Satanta promised peace if released, and even said he would personally kill some war-minded Kiowas. The jury, however, found Satanta guilty and sentenced him to death.

The trial of the century was over, but it didn’t end there. Bowing to political pressure and fearing Kiowa retaliation if the death sentences were carried out, Soward wrote Gov. Edmund J. Davis on July 10, pleading with him to commute the sentences to life imprisonment. Davis agreed, and on October 16, Satanta and Big Tree were transported to the state penitentiary in Huntsville.

Following the trial, Woolfolk continued practicing law while improving his farm and ranch operation on the Brazos River. Ball went on to become a state senator and assistant attorney general of Texas, but the trial propelled Lanham into the statehouse. He served as Texas governor from 1903-1907, and was the last Confederate veteran to hold that position.

Satanta and Big Tree were paroled in 1873. An infuriated Sherman wrote Davis “that I believe Satanta and Big Tree will have their revenge, if they have not already had it, and that if they are to have scalps that yours is the first that should be taken.”

Big Tree, however, settled down. He worked on a supply train after his parole, helped establish the Rainy Mountain Indian Mission and joined the church in 1897, serving as a deacon until his death in 1929.

Satanta, on the other hand, took part in the Red River War of 1874-75, and was shipped back to Huntsville after he surrendered. Other Kiowa leaders were also punished, such as Maman-ti—the real leader behind the Warren wagon train raid. Maman-ti was sent to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, where he died of consumption in 1875.

Satanta’s health quickly faded in prison. Told that he had no chance of parole, he said, “I cannot wither and die like a dog in chains.” The following day, October 11, 1878, he slashed himself and was taken to the second-story prison infirmary to stop the bleeding. Left alone, he jumped from the landing to his death.

In many ways, the Kiowa trial became a catalyst for the demise of the Quaker Peace Policy on the reservations and the defeat of the Kiowa nation. As historian Allen Lee Hamilton writes: “Many raids were far more destructive in terms of lives lost and property destroyed than the one that struck Henry Warren’s wagons on May 18, 1871, but few if any have had more far-reaching effects.”

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Texas State Library & Archives Commission –

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy Texas State Library & Archives Commission –

– Courtesy National Archives –